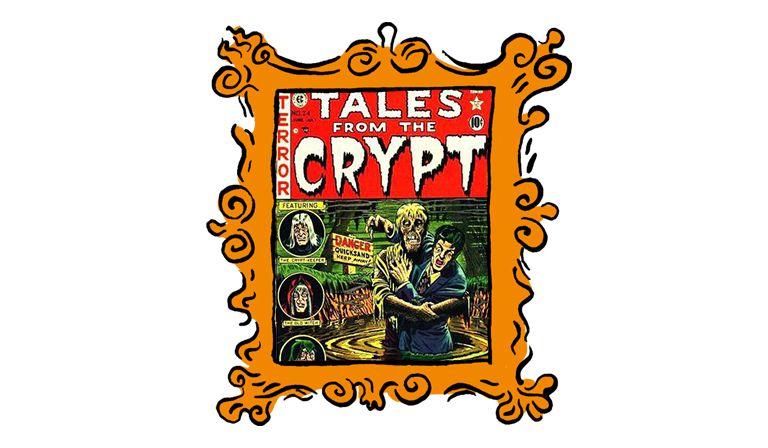

Seventy years ago, the final issue of a comic book called Tales from the Crypt landed on the newsstands of America. It was, as you can probably guess, a horror title, featuring often gory sting-in-the-tail short graphic stories, which were lapped up by readers.

Comic books come and go, but it wasn’t really changing tastes or economic reasons that had killed off Tales from the Crypt and the other horror titles published by EC Comics, including Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear and Weird Science. EC Comics, and especially the company’s publisher Bill Gaines, had been held up as the prime examples of everything that was wrong about the American comic industry in the 1950s and found themselves at the centre of nothing less than—appropriately enough for a publisher of horror comics—a witch-hunt.

EC Comics had been founded in the 1930s by Maxwell Gaines, initially to produce child-friendly fare—the EC stands for Educational Comics. When Max Gaines died in a boating accident in 1947, his son Bill took over the company and steered it in a more adult-oriented direction. EC’s output became more fantastical, more bloody and more violent. So it was almost inevitable that they came to the attention of the establishment… in this case, in the form of a psychologist called Fredric Wertham.

German-born Wertham had lived in the US since 1922 and worked in a New York hospital which assessed people often accused of violent crimes. After the Second World War, he opened a clinic in Harlem to treat psychiatric conditions among poverty-stricken black kids, and it was here that he noticed the popularity of what he gave the catch-all term “crime comics”, whether they were horror, science fiction or even superheroes.

Wertham was convinced that comics were having a detrimental impact on the development of young American minds, and he wrote about it in a book that was released in 1954: Seduction of the Innocent. The book is perhaps most infamous for the potshots it took at today’s cultural icons, including: Batman and Robin (he thought the adult Bruce Wayne living with the young Dick Grayson was “a wish-dream of two homosexuals living together”); Wonder Woman, whom he suspected to be a lesbian; and even the moral paragon Superman, whose ability to leap tall buildings in a single bound gave children unrealistic expectations of what they could achieve in life.

But it was EC Comics that Wertham really got worked up about, and his book caused a flurry of hand-wringing editorials in the American press. One particularly coruscating article in the Hartford Courier breathlessly reeled off the degeneracy in a single issue of Tales from the Crypt: “The first story in it is about adultery and murder. The second is about a man who drowns his best friend in order to steal his best friend’s girl. The third features a homicidal maniac and his sister who are boiled to death in hot water. The final story opens with a sadist torturing animals to death, then turns to murder with a butcher knife and an axe, and ends with the killer being burned to death in a flaming car.”

Grant Geissman, a writer and comics historian, concedes: “Presented in this way —stripped down to their bare bones, divorced of the punning, tongue-in-cheek interjections and without EC’s trademark Old Testament-style ‘eye-for-an-eye’ morality — the stories do sound absolutely horrific.”

But those were important factors in EC Comics. The publisher pioneered the idea of the “horror host”—each of its comics was curated by a fictional character, such as the Crypt-Keeper, the Vault-Keeper or the Old Witch (together styled the Three GhouLunatics) who introduced each story in an acerbic style and usually ended on some terrible wordplay. And the moral of the story was usually: if you do bad things, then absolutely awful things will happen to you in return.

That, however, seemed lost on Wertham and his media supporters. It might have been a short-lived moral panic, but it coincided with work being done by the Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency—and, not ones to look a scapegoat in the mouth, they immediately set up a two-day hearing to investigate the effect of comics on the nation’s youth.

Geissman has written a big treatise on EC for the art-book publisher Taschen, which published it in its monstrous but beautiful XXL-sized edition as The History of EC Comics. The company is also starting to release in the same format (40cm tall and 30cm wide, and clocking in at £150) the original strips, starting earlier this year with Weird Science, which ran from 1950 to 1952.

Geissman recounts in The History of EC Comics how Gaines tried to contextualise horror comics and to defend the ability of children to see right from wrong. Gaines told the committee: “What are we afraid of? Are we afraid of our own children? Do we forget that they are citizens, too, and entitled to select what to read or do? Do we think our children are so evil, so simple-minded, that it takes a story of murder to set them to murder, a story of robbery to set them to robbery?”

The committee did, and the public seemed to agree with them. Geissman writes: “Horror and crime comics became hot potatoes, and thousands of copies of EC comics were returned to the distributors in unopened bundles. Worse, a number of do-good groups around the country began comic-book-roundup drives, where horror and crime comics were gathered up and ignited in massive book burnings.”

What emerged from those hearings was the creation of the Comics Code Authority, a sort of censorship body that ensured storylines were sanitised for years to come. Gaines dropped his horror and crime titles, ending with Tales from the Crypt issue 46, dated February/March 1955. He tried some new ideas, but, in the end, the only title to survive was the long-running humour magazine Mad.

We might consider we now live in more enlightened times. For those who think it couldn’t happen now, though, consider this: the American Library Association keeps a watchful eye on the number of challenges to comics and graphic novels—complaints by parents and members of the public who object to the content of books in public and school libraries, and demand they be removed.

In 2015, there were 40 total censorship attempts on 33 individual comic titles. That figure remained pretty steady up until 2021, when things ballooned. That year, there were 392 censorship bids against 114 titles; in 2022, that more than doubled to 868 censorship bids; and, in the latest figures, for 2023, there were 1,020 calls for 378 comics and graphic novels to be removed.

Horror comics are having something of a resurgence at the moment, especially in the US. Try Somna by Becky Cloonan and Tula Lotay (DSTLRY), Something is Killing the Children by James Tynion IV and Werther Dell’Edera (Boom! Studios) or Houses of the Unholy by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips (Image) if you’re interested. But don’t get too comfortable with those books in your hands. Some 70 years after the censors killed EC Comics, the unalloyed delight of horror in graphic form could once again be under dire threat.

Will the age of Trump see off scary comics (again)?

It’s 70 years since the final issue of ‘Tales from the Crypt’–it was killed off, after years of popularity, during a moral frenzy

May 01, 2025