Barcelona under Franco was very grey, very boring, but Cadaqués was very colourful. There were a lot of foreigners, things happening; it opened my eyes,” explains Antoni Muntadas, one of the leading Catalan artists of recent decades and a prominent member of La Gauche Divine, Barcelona’s underground group of intellectuals who led the region’s cultural renewal and still meet occasionally. The sprightly 83-year-old first visited Cadaqués, on the Costa Brava, in 1956 and has been coming every year since.

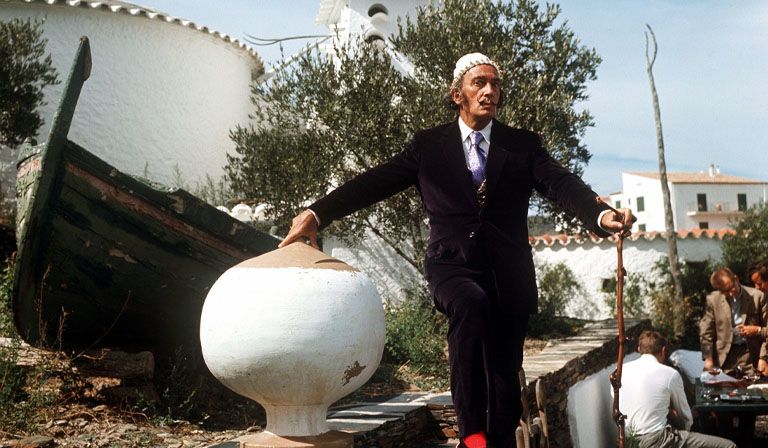

We are chatting in the Maritim café-bar, an enormous conservatory on the beach, filled with exhibition posters from the town where the avant-garde met the anarchic, including UK pop artist Richard Hamilton (who renovated a house here), Marcel Duchamp (who summered here for nine years, and first invited Hamilton), Salvador Dalí, Man Ray and Mary Callery, a sculptor who modelled for Picasso and Matisse.

Muntadas is telling me about “Sadomasoqués”, an exhibition based on his idea that artists who spend time here have a joyfully painful relationship with the place.

“Sadomasoqués” was shown in Galeria Cadaqués, the oldest gallery in town and part of a former sardine factory transformed into exhibition spaces and studios by the architect Lanfranco Bombelli. Opening in 1973, it is the gallery that has probably done most to establish the town’s artistic reputation. Its owner, Huc Malla, explains that Hamilton had 14 solo exhibitions here and they also hosted the first solo shows in Spain of Duchamp, Jasper Johns, David Hockney, RB Kitaj and Tacita Dean. Brits Peter Fillingham and Oliver Chanarin, along with Dean, were included in “Sadomasoqués”. As the writer Vicenç Altaió states in the exhibition notes, “Cadaqués shocks, captivates and at the same time provokes a certain rejection.”

The town is captivating indeed, its white houses rising from the slate bed left by the foothills of the Pyrenees as they slide into the sea. You will encounter many a rastell—Catalan for a steep path made of pieces of slate set vertically (like walking across a bed of nails!)—as you wander the narrow streets vivid with the blossom of bougainvillea. There are numerous galleries: Marges-U, with its amazing bare slate-wall interior where Japanese artist Nobuko Kihira shows her work merging Asian and Catalan traditions; or the cavernous studio of Javier Aznarez, whose satirical graphics attracted Wes Anderson’s producer and resulted in designs for Anderson’s 2021 film, The French Dispatch. Here, even the electricity boxes have their doors painted with seascapes.

Political comment is, of course, not absent from a Catalan enclave facing threats to its identity. Colourful collages abound questioning patriarchy, tourism and fashion-capitalism, and a large mural spells out “October 1, 2017. We voted, we won INDEPENDENCE”—a reference to the Catalan independence referendum, which was outlawed by Spain’s constitutional court.

Cadaqués owes much of its character, its fervent nos amb nos attitude (“us with us”) to its geological surroundings in Alt Empordà, northeast Catalonia. Not far from the centre, the Cap de Creus nature reserve turns into an astonishing expanse of stone walls, olive groves and mountains—look, there’s France!—with baking coves of sparkling sea, and, in the Tudela part of the park, those rock formations that so enchanted Dalí.

On the other side of town, the Pení mountain blocks the setting sun, casting Cadaqués into long, mauve twilights that turn the sea bewitching shades. A single road twists sharply among rocky groves towards the overdeveloped resort of Roses.

Then there’s the light. As acclaimed Catalan author Josep Pla wrote in his 1947 book Cadaqués, it is “a light that does not absorb, that does not correct, that does not drown or melt… the shape of things”. And it has lured countless important artists, beginning with impressionist Ramon Pitxot (who invited Picasso) and including landscape painter Eliseo Meifrèn, the first to have a studio in Port Lligat.

If the light and landscape inspire a feeling of creative joy, then the Tramuntana can bring trouble. Blowing from inland, the northern wind cleanses sky, sea and minds, but its relentlessness also drives many to despair, as Gabriel Garcia Márquez captured in a short story of that name. He also noted that the single access road was little more than “a narrow, winding ledge on the edge of a bottomless abyss”. In the old days, it was easier for locals to jump on a ship to Cuba than to travel by horse and cart over the Pení to Girona. Now, that single road is all that prevents the town from being completely overwhelmed by tourists.

Tourism was already a problem when Antoni Muntadas made Cadaqués Canal Local, a series of filmed interviews in which locals expressed their views of summer visitors back in 1974. Screenings followed at Maritim and at Casino, a busy arts and social centre. In response, Franco’s secret police raided the town, believing a subversive TV channel was being aired.

Before electricity, the area was known for sailors and coral divers, pirates and witches

Cadaqués never lacked a counter-cultural edge. Before electricity, the area was known for sailors and coral divers, pirates and witches. Then came the musicians and artists, to create magic in this cauldron of creativity and mythology, “the laboratory of the modern”. Today, this legacy is upheld by the likes of Josep Moscardó and his twin brother Ramon, both flamboyant and successful painters. “I was all day naked,” says Josep remembering his early time in Cadaqués in the 1970s. “Back then it was still possible to find mussels, a little bread and botifarra [Catalan sausage] and live with very little. Paint on the beach, cook paella on the beach.” The twins’ buoyant canvases capture all the light and life of the town, from dancers in beach taverns to picnicking lovers in the olive groves, all in an exuberant style that never descends into kitsch, even if the warm glow has much to do with nostalgia.

German artist Daniel Zerbst came to Cadaqués in 1998. Even then, he says, “There were still hippies and punks living on S’Aranella island in Port Lligat, or occupying houses. People came to take LSD on a full moon at the Cap de Creus, or they came because they’d read Pla, Marquez, Lorca. It was cheap, so people wanted to paint and write here. That’s gone now.”

This summer marked the centenary of Lorca’s first visit to Dalí in Port Lligat. His “Ode to Salvador Dalí” includes three verses about Cadaqués, where “fishermen sleep dreamless on the sand”. There is a bust of the poet just before Llané Gran beach, but it’s lost among the blossoms behind a parking space.

Rudi, the Belgian owner of the legendary café-bar Brown Sugar also bemoans the shutting-down of the bohemian way of life. Using recycled materials, he renovated a former tailor’s shop 16 years ago, extended next door to an erstwhile bakery and retained original tools and a baking table, “so people can see some old town history”. The stone walls beneath the original curved ceiling display paintings by Danny Rauch, whose wife modelled for Dalí. “There used to be barbeques and music on the beach, spontaneous concerts on every terrace,” says Rudi. “People felt very free. It’s been outlawed now.”

Rudi suggests the decline began when Hostal bar closed. Hostal was the nerve centre of arty nighthawks, open until 4am, but now a tourist eaterie. “Sometimes I feel like the last of the Mohicans,” he adds.

CREA (Collective for the Representation and Evolution of the Artistic scene of Cadaqués) is trying hard to sustain the town’s cultural identity. A private organisation in its second year, CREA looks after the street art, produces the “Art Nights” of open galleries in the summer and puts together frequent exhibitions in the Casino. Without funding from the local council, CREA relies on the fees of 170 members, the president, Eva Daniel, tells me. “We even have one in London!”

A visiting artist interrupts us. She has an exhibition opening at the Casino tomorrow, but explains she’s had to rent a very expensive Airbnb apartment. I ask Eva whether there are any artist residencies available. She shakes her head. “It’s so hard to convince the public and town hall that we need support. Sometimes I put up artists in my own flat.”

Beneath all this lies the painful truth of a housing crisis caused by tourism. Of 3,200 living units, 1,400 are temporary rentals for tourists, and 1,000 are second homes bought by rich Catalans or by the French who travel down the coast in their sports cars and SUVs and buy up properties for about half the amount they would pay back home. This doesn’t leave much for the 3,500 Cadaquésencs. Long-established Catalan families are moving out, artists can’t afford studios or exorbitant summer rents, and seasonal workers from South America can’t find anywhere to sleep. Even worse, at least 70 per cent of the properties are locked up during winter.

The council says that, in response, it will no longer renew Airbnb licences—but is it already too late? It might be, for this is the age of the prijo, Catalan for a snob with money but no artistic sensibility. “Every year is worse. They’re trying to turn it into St Tropez. Every day, fancier clothes, fancier cars,” explains Marcus from the Expo Dalí museum in town, a fascinating collection of Dalí’s often overlooked graphic work, including his magnificent book illustrations.

Cadaqués has become an Instagram sensation, a location for daytrippers seeking selfies

Since Covid, Cadaqués has become an Instagram sensation, a prestigious location for daytrippers seeking selfies and gelato. The infrastructure is overloaded. Marcus also explains how the Cadaqués International Music Festival once boasted illustrious performers such as Montserrat Caballé, but in recent years has been scaled down, underfunded.

Bar Boia on the beach, close to Maritim, was another well-known meeting place for the avant garde and artisans alike. It was closed down earlier this year in accordance with Madrid’s Coastal Law—which purports to spare the country’s beaches from excessive development—even though the structure had been awarded protected status by the local council in 2018. An artist daubed Boia’s windows with flowing images of clientele, another spray-painted the names of illustrious visitors. Two days later, they’d been scrubbed away. A protest manifesto remained, citing “a direct attack on the collective memory of Cadaqués”.

I meet with Kixe Grau from the Friends of Nature of Cadaqués, an organisation that represents the SOS Costa Brava group. They’ve had some success, blocking a huge housing development in the hills above the town, but now there’s a plan for 4,000 new properties. For locals? “Pretty much none of them,” she replies.

Then there’s the Russian-backed hotel under construction on Sa Conca, on the site of a famous 1970s hotel which was demolished. It’s the bay where Dalí first painted during family holidays and visited Ramon Pitxot. After moving to Port Lligat, Dalí would return to Sa Conca to see his muse, Lidia, purportedly the daughter of the last witch of Cadaqués. Her hut still exists, bearing an information plaque, but few know of it because ownership is shared between the neighbour and the local council. On the other side of the bay, the Pitxot family home remains.

“In the end,” says Kixe, “tourism destroys what it is looking for.”

Thankfully, not every visitor is a prijo. Many still buy art. Next door to Galeria Cadaqués along the gently sloping, rather picturesque Carrer Hort d’en Sanés, you’ll find Taller Galeria Fort. Each year, the gallery hosts an international mini print competition attracting around 650 artists, who each send in four copies of a small graphic work. One goes in the gallery’s summer exhibition, the second and third are for sale, and the fourth goes to a partner exhibition in Wingfield, Suffolk.

“This is a special gallery because we only sell nice-price works, €20 to €60, not €3,000, so even if there’s a crisis, people still come here to buy,” explains Aleix Canal, the founder’s son-in-law. “They’re cheap, easy to take, easy to hang, so it’s always going well.”

As for everyone else? “I can see how the galleries are disappearing. Only one gallery has opened in the last 20 years.” Indeed, in Cadaqués, there are now nearly as many real estate agencies as there are exhibition spaces.

A prominent gallery that has survived is Patrick Domken’s, just a few steps away. Domken has been in Cadaqués for 50 years, running the stylish gallery for 26 of those. Locals speak highly of him, not least because he hosts free events nearly every weekend and throughout the winter. I attended performances by an opera singer, a pianist and a poet, during the exhibition of another Japanese artist who lived here, Koyama. His bold canvases of the rocky coves of the Cap de Creus are striking.

While much of the town’s charm is fostered by its galleries, a new energy is generated when they are taken over for two weeks in October by the Incadaqués Photo Festival, showing the selected work of established and emerging photographers from around the world. “Collectors come, everyone sells something,” says director and founder Valmont Achalme. More than 500 people attend the opening weekend. Photos are also displayed on the streets, the beaches, even under water; it’s the most accessible, most contemporary cultural event of the year, and it’s fast gaining an international reputation. The festival is funded privately and by ticket sales for the vernissages.

This sharing of spaces looks like the way forward. An empty 19th-century former nunnery under the Santa María church provided the spectacular setting for the closing weekend of this year’s Arxipèlag festival of avant-garde films. There are plans to develop the venue, already named Atrium Artium, into a “dynamic place to promote culture, education, dialogue and peace”. You would suspect that, with more collaboration between the various cliques of Cadaqués, similar solutions could be found.

After all, the council has finally located a building to house the town’s library. Motor Mur, the editor of Sol Ixent, a quarterly magazine covering the area’s history and art heritage, has been campaigning for a library for years. Despite the current list of concerns, Mur is keen to tell me that he wouldn’t want to live anywhere else, and that in a recent exhibition of aerial photos, showing the Costa Brava in the 1950s and again in 2018, Cadaqués clearly emerged as the least developed town. “We’re inside a national park, otherwise it would be far worse.”

On my last night, I’m driven through the park, up to the Cap de Creus restaurant, sister establishment to the excellent alternative live music venue Can Shelabi, back in town. It’s a spectacular journey, with those foothills in silhouette against a pink sky, as the sea begins to merge with a starlit night. I’m with Natalia, who has a gallery for her sculptures; with Javi, the witty graphic artist; and with Jenny, originally from Sicily, who makes jewellery and now lives in Cadaqués full time, having fallen for “its colours, its winds, its light”.

After the meal outside, we walk back to the car park under the lighthouse, the rotating beam of which somehow doesn’t detract from the resplendent constellations above. And there are shooting stars. Many of them. We decide to lie on our backs and observe. Amid the oohs greeting each flaming meteoroid, a voice says, “About your article… just don’t encourage more people to come here, okay?