When 18-year-old Bernie Sanders enrolled as a freshman at Brooklyn College in 1959, the two-storey, 2,400-seat art deco theatre on campus was called the Walt Whitman Auditorium. It had opened four years earlier and was one of the largest performance venues in New York. In 2018 the name of Whitman, who spent part of his itinerant childhood in the borough, was dropped to commemorate an alumni couple who had made their fortune in the cable network business and donated $10m to the college. So on the first Saturday of September 2025, when Sanders returned to his alma mater on the eve of his 84th birthday, he took to the stage of the Claire Tow Theater inside the Leonard and Claire Tow Center for the Performing Arts. Despite the makeover, there were scabs of moisture on the ceiling, from where a huge mesh net was suspended to catch the peeling flakes of paint.

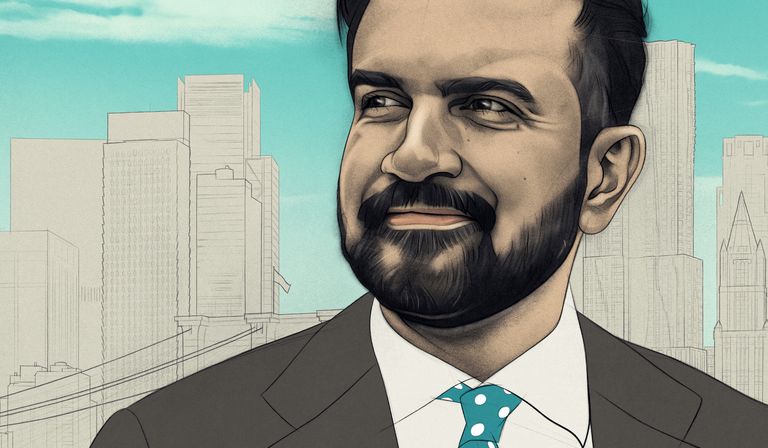

The packed Brooklyn auditorium welcomed Sanders with loud cheers which rose by several decibels at the arrival of his co-host Zohran Mamdani, the surprise frontrunner in the New York mayoral election. Over the summer, in a historic campaign, Mamdani had risen from near political anonymity to triumph in the Democratic primary, winning the most votes ever by a candidate in the city’s history.

A Uganda-born 33-year-old with Indian heritage, Mamdani ran on a message that easily resonates at a time when renting a studio in Lower Manhattan costs more than $3,000 a month, plus amenities: that New York is too expensive. In smartly produced short videos shot on the streets, he promised to raise the minimum wage, freeze rent, build more affordable housing, open city-owned grocery stores, make childcare free, waive the $2.90 charge for bus rides, and pay for it all by raising corporate tax by 4 per cent and introducing a 2 per cent income tax on New Yorkers who make more than $1m annually.

It is a highly ambitious agenda, and Mamdani’s critics have fairly pointed out that his political inexperience could be a barrier to delivering it. Since 2020, he has represented the 36th district in Astoria, Queens, in the New York State Assembly. Even his supporters, many of whom cite his outsider status in mainstream politics as a good thing, do not deny that Mamdani might be unable to do everything he is promising. “But even if he gets some of these things done, it will make a great difference,” one of the volunteers for Mamdani’s campaign told me. “In Zohran, we at least have a politician who talks about how high the rent is in the city.”

Many of the New Yorkers sitting in the audience at Brooklyn College had canvassed for Mamdani. His campaign has 50,000 volunteers, mostly twenty- and thirty-something professionals who are spending their weekends knocking on doors and phoning prospective voters before election day on 4th November. In the two weeks leading up to the registration deadline for the Democratic primary, he drew young first-time voters to the ballot box. More than 36,000 people registered to vote: a tenfold surge from the number of people who registered in the same period in 2021. Within minutes of appearing on stage in Brooklyn, he had the audience chanting: “Freeze the rent!”

This event was a pitstop on Sanders’s “Fighting Oligarchy” tour, which started in Nebraska a month after Donald Trump began his second term in office and has since visited more than 20 states. In Denver, Colorado, he drew crowds bigger than Kamala Harris had managed in Texas when she had the assistance of Beyoncé. In deep-red Utah, people lined up at the venue at 8.30am, seven hours before the doors were supposed to open. His message of tackling rising economic inequality in the United States has resonated, too, with people in Idaho and Arizona.

During his five-decade political career, Sanders, the longest-serving independent senator in congressional history and a self-described democratic socialist, has repeatedly raised alarms about growing inequality in the US. In his presidential campaign in 2016, before losing the Democratic primary to Hillary Clinton, he called inequality “the greatest moral issue of our time”. These days, he can point to obvious images. In Wisconsin, he reminded people of the Silicon Valley billionaires seated in front of Trump’s own cabinet members during the inauguration ceremony in January, each of whom had poured $1m into an “inauguration fund”: “Today we have a government of the billionaire class, by the billionaire class, and for the billionaire class.”

As if to illustrate the point, Republican party seniors have advised their elected lawmakers to avoid in-person town halls, where they are likely to face hostile crowds asking about federal job cuts and the rising cost of healthcare. The Democrats rushed to fill the gap, but those town halls were not as well attended as Sanders’s rallies. “I don’t know if I’m part of the [Democratic] party anymore—they’ve really failed us in a lot of ways,” a 28-year-old told a reporter in Tucson, Arizona, where about 20,000 had gathered to listen to Sanders. “They need to work on messaging, they need to work on getting the old guard out of office and actually letting the progressive wing of the party that represents the people through.”

Since his win in the primary, New York’s real estate lobby has spent millions trying to attack Mamdani

Mamdani told the audience that Sanders’s presidential campaign in 2016 had given him “the language of democratic socialism”, describing him as “an icon of our struggle”.

He commanded the crowd easily. On cue, he got everyone to stand up, clap their hands and, in the end, to join in singing “Happy Birthday” to Sanders. When Sanders spoke, he hailed Mamdani’s campaign. It was not made up of ugly 30-second TV ads, but a grassroots movement, he said, as well as “a test case of whether democracy is still able to prevail in this country”.

Since his win in the primary, New York’s real estate lobby has spent millions trying to attack Mamdani and boost his rivals. Trump himself pressured current mayor Eric Adams, running as an independent, to drop out—which he has now done—in order to boost the candidacy of Andrew Cuomo, the former Democratic governor of New York state who resigned in 2021 over multiple allegations of sexual harassment. (Cuomo has also been accused of corruption.) “What you are seeing now is an oligarchy with enormous economic power and political power in both political parties… they are afraid of Mr Mamdani becoming an example of what can happen all over the country,” Sanders said. “They are scared to death.”

Here, Sanders was addressing the Democratic party’s muted response to Mamdani’s rise. Cuomo, despite the accusations against him, was preferred by the editorial board at the New York Times—a reliable channel for the official positions of the Democratic party. Established New York Democrats, including Chuck Schumer and Hakeem Jeffries, have not endorsed Mamdani, the socialist son of a Muslim father and Hindu mother who speaks up for the Palestinians. And yet most polls indicate that Mamdani has a substantial lead over his opponents. Schumer’s approval rating, just like that of the Democratic party, is currently below 30 per cent.

The first 10 months of Trump’s second term have been eventful enough to fill an entire administration. The government has financially gutted the universities, deployed the National Guard to -Democratic-led cities and instituted a tariff regime on imported goods that fluctuates with the whims of the president. Elon Musk, the world’s richest man, with whom Trump had a brief bromance, fired tens of thousands of federal employees, reportedly in a ketamine-induced daze. Meanwhile, masked agents of the state have abducted immigrants and students from streets, airports and courthouses. Some have been locked in private for-profit prisons around the country, others flown to the notorious Terrorism Confinement Center in El Salvador, later described by one inmate as “hell on Earth”. The genocide in Gaza continues unabated.

In the week before Sanders and Mamdani spoke in New York, Trump had signed an executive order renaming the Department of Defense as the Department of War. Two days earlier, US forces bombed a boat in the Caribbean Sea, killing 11 people whom Trump alleged were terrorists. When asked what legal authority he had to strike a boat in international waters, the secretary of war Pete Hegseth responded that he had “the absolute and complete authority to do that”, adding: “I’d say we smoked a drug boat and there’s 11 narco-terrorists at the bottom of the ocean and when other people try to do that, they’re gonna meet the same fate.”

Through it all, the Democrats have been playing the proverbial flute. They have failed to cohere any meaningful opposition to Trump or his policies. The former president Joe Biden, who dismissed concerns about his health while seeking re-election last summer, has been diagnosed with cancer. His deputies are now telling reporters that Biden was not in full possession of his faculties while in office. Kamala Harris, who replaced Biden as the presidential nominee only to lose to Trump, has just published a book for which she was reportedly paid $20m. In it, she accuses Biden of trying to sabotage her campaign, out of spite for having been made to drop out of the race. Two months after Trump took office in an election that, the Democrats repeatedly insisted, was going to decide the fate of democracy in the US, senate minority leader Schumer said in an interview that his job, as he saw it, was “to keep the left pro-Israel”.

It is a goal out of step with the feelings of the electorate. According to one poll by Quinnipiac University, only 12 per cent of Democratic voters say they sympathise more with Israelis than Palestinians, while 60 per cent say they are more sympathetic towards Palestinians. (In 2017, for comparison, Quinnipiac found over 40 per cent of Democratic voters favoured Israel.) At a town hall in August, the Democratic senator for Arizona Ruben Gallego was confronted by a voter about the party’s position on Israel. “The people of Gaza are in this situation because Donald Trump is president,” Gallego responded. “Biden was there too,” the voter reminded Gallego, who shrugged in response: “Whatever, hey, this is your opinion dude.”

Those with memories longer than the second Trump administration recall that Israel’s war in Gaza had continued for 15 months with the blessing of a Democratic administration. The dismantling of the universities by Trump was an extension of a campaign by Democrats against pro-Palestinian student protesters. Masked agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) abducted Ivy League students whom Democrats like John Fetterman had demonised as terrorist sympathisers. Lies and obfuscation about ceasefire negotiations and the conduct of the Israeli Defense Forces were already the norm for White House press briefings in 2024. Outside the Democratic National Convention, attendees covered their ears and mocked the protesters who were reading to them the names of Palestinian children killed by Israel.

“We are at a moment where people are asking themselves: why can’t the Democratic party defend this assault on democracy?” the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates commented earlier this year. “I would submit to you that if you can’t draw the line at genocide, you probably can’t draw the line at democracy.”

Morality does not guide American politics, but the Democratic party is also unmoved by self-interest. Recent headlines have described the Democrats as powerless, spineless and in an identity crisis. A senior party strategist said in June, “We’re leaderless, we’re messageless, we’re agendaless.” Donors and strategists, a report said in March, “have been gathering at luxury hotels to discuss how to win back working-class voters”. Their ideas include spending $20m to study the “syntax, language and content that gains attention and virality among young voters”. The party has cornered itself into ubiquitous irrelevance at perhaps the most perilous time for the country in modern history.

“I find it hard to understand how the major Democratic leaders of New York state are not supporting the Democratic candidate [Mamdani],” Sanders said in Brooklyn. “If a candidate started at 2 per cent in the polls, gets 50,000 volunteers, creates enormous excitement, gets young people involved in the political process, gets non-traditional voters to vote, Democratic leaders would be jumping up and down!”

Mamdani’s progressive policies and his frank criticism of Israel were equally crucial to the success of his campaign. The loudest cheers during the Brooklyn town hall came when Mamdani or Sanders brought up Palestine, even in passing. Several volunteers I met during the summer were most impressed by Mamdani’s unwillingness to cede ground when faced by so-called loyalty tests. One woman who canvassed in Queens for the campaign told me that, for her, the most telling moment of the primary debate was when the moderators asked the candidates where their first foreign trip as mayor was going to be, and each one responded: Israel. Except for Mamdani, who said he will stay in the city to make it a better place.

But these same qualities make him unappetising to the party leadership. Schumer’s hesitance to endorse Mamdani, it was reported in August, springs from his “sense of responsibility to Jewish voters, and the influence of donors and Democrats in New York City, particularly in the real estate industry, many of whom are vocal with their concerns about a Mamdani mayoralty”. The report, published in the New York Times, failed to mention that many polls, including one conducted by the paper itself, demonstrate that Mamdani is the preferred candidate for mayor among Jewish New Yorkers.

This kind of ambient suspiciousness has permeated the coverage of Mamdani in the paper. As Adam Johnson, a media analyst based in New York, wrote in August, the Times has “used innuendo, sectarian framing, and a heavy dose of weasel words to repeatedly imply that Mamdani was uniquely struggling to win the support of New York’s Jewish voters”. In one month across June and July, Johnson found, the Times ran 32 articles about Mamdani’s refusal to condemn the phrase “globalise the intifada”.

’Income inequality is the core of the problem and Bernie is the only politician who talked about it. Zohran is carrying on that work.’

American journalists have insisted that Mamdani declare whether he believes in Israel’s right to exist, which is a question you don’t ever hear about another country. His answer—that he believes that Israel has a right to exist as a state with equal rights—only led to more accusations of antisemitism, including by those who invoke the word to intimidate the critics of Israel. Democratic voters are increasingly unmoved by this distortion, but Democratic leaders such as Schumer are clinging to it at the risk of alienating their electorate.

After the event, as it was starting to drizzle, I chatted outside with Ross, a 34-year-old. He had moved to New York from Pittsburgh 20 years ago, lives in Queens, works for the city government and canvassed for Mamdani during the summer. Growing up, he said, he had seen the effects of de-industrialisation in Pennsylvania—the joblessness and despair that, he said, “Trump harnessed into a political constituency”. I asked what drew him to Mamdani’s campaign. “Americans are being cheated,” he told me. “Income inequality is the core of the problem and Bernie is the only politician who talked about it for the longest time. Zohran is carrying on that work.”

Working for the campaign and watching Mamdani’s historic win in the primary, he said, was an extraordinary experience. The night the votes were counted, he realised, “I am not a minority in New York.” Ross spoke about the cost of living in the city. One of the audience members had said that childcare costs her over $30,000 annually. “It really is that much,” Ross said. “Those are the sort of things we need our politicians to address.”

“It is terrifying to watch Trump use the greatest military in the world against American citizens,” Ross continued. “What can you even say? He does whatever he likes. Did you see they changed the Department of Defense to the Department of War?” I asked what he thought of the Democrats’ response. “What response?” he shrugged. “I guess I wasn’t really counting on those guys to stand up to Trump when they couldn’t even stand up to Netanyahu, but it is really shocking how completely useless the party has been over the last months.”

Was he surprised by their passivity? “Not really,” he said. “They sold out a long time ago.”