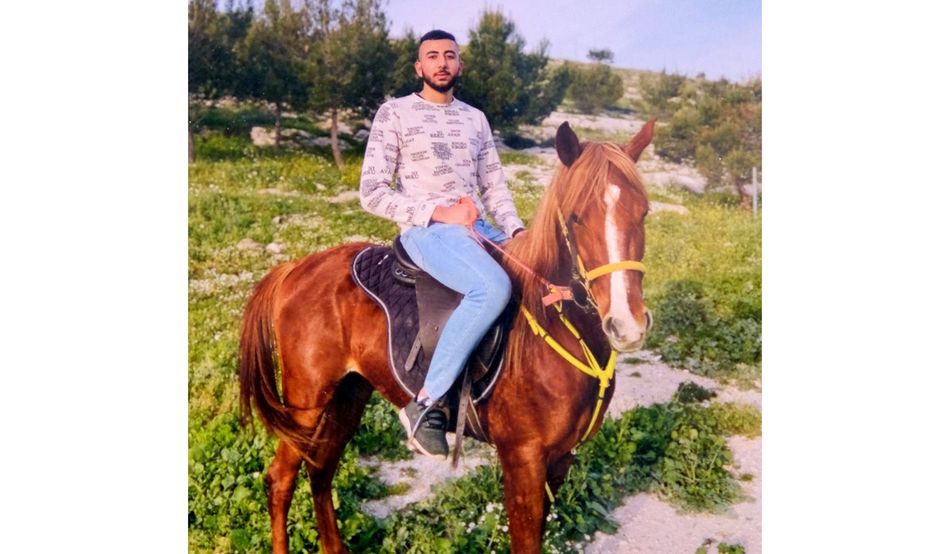

The killing of Ahmed Barahmeh in the West Bank village of Anza on 24th September this year passed almost unnoticed in Israel, apart from a cursory mention that day in the live blog of the Times of Israel, an English-language outlet. The 19-year-old teenager had hurled a bomb at Israeli troops, or so that headline said. He was shot dead. Case closed.

Such incidents have an almost dog-bites-man quality about them—more than 1,000 Palestinians have been killed in the West Bank since the Hamas massacre of 7th October 2023, but few of those deaths make news in Israel.

Only a small minority of Jewish Israelis pay much attention to what has been going on in the occupied territories, or the suffering of those killed, injured, starving or displaced during the two-year war in Gaza. Most of the Israeli media has ignored it.

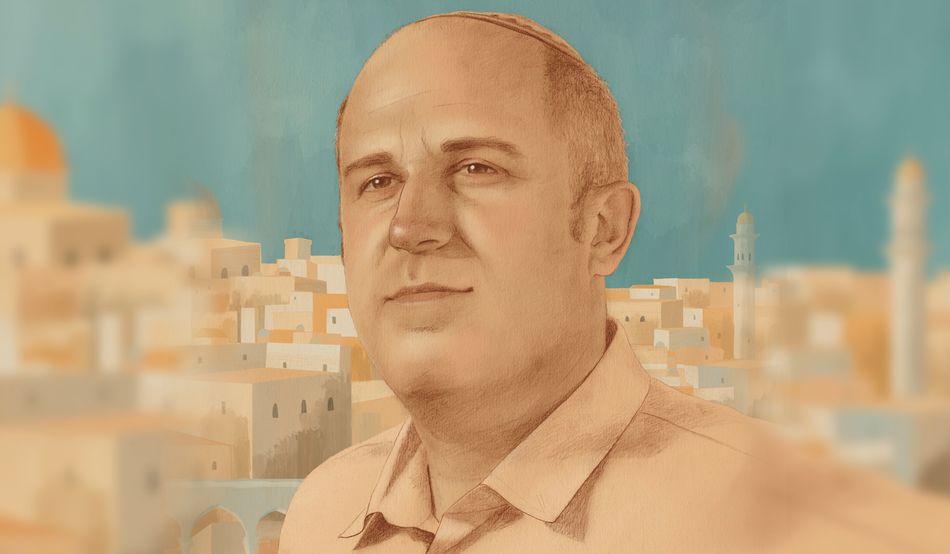

But this particular shooting would not go entirely unremarked in the Hebrew press. Eleven days after Barameh was killed, Gideon Levy, a veteran journalist for the Israeli newspaper Haaretz set off from his home in Tel Aviv to discover what happened to Barameh.

For nearly 40 years, Levy, now 72, has made it a personal mission to travel to the West Bank every week to report on what’s happening there. On that day, as always, he was accompanied by Alex Levac, 81, an award-winning photographer who has worked with Levy on his column, the Twilight Zone, for the past 15 years. Levac won the prestigious Israel Prize in 2005. He wears his renown modestly.

Levy is both passionately admired and vehemently loathed within Israel. Depending on your view, he is either one of the few journalists to have kept an unrelenting spotlight on the suffering of Palestinians, or he is something close to being a traitor to Israel and to the Zionist cause. But to those Israelis who do pay attention to such matters, he embodies the spirit of Haaretz—a newspaper which, like Levy, is both revered and reviled.

If such criticism troubles Levy, he doesn’t show it on the morning I accompany him to meet the deceased teenager’s family. He folds a yellow A4 notepad into the cargo pockets of his weathered grey fatigues and we set off on Route 5, the main west-to-east road which links Tel Aviv with Ariel, a large West Bank settlement of more than 22,000 people.

There’s a Beethoven piano trio on the car radio as Levy describes the routine which, since 1988, has seen him make this weekly trip. “It’s very frustrating because nobody is reading it, and still, we think it is important to document these things,” he says in a tone of mordant resignation.

“We do it all over the West Bank. Every week another place. The stories repeat themselves because the occupation repeats itself. But things got much worse in the last two years. The West Bank has dramatically changed… and you will see it.”

Over the next hour, as we cross the Green Line which marks the de facto boundary between Israel and the occupied territories, Levy points out numerous blue-and-white Israeli flags planted throughout the landscape. “You see them all over the place,” he waves towards one a few metres from the road. “The settlers realised that the war in Gaza is their opportunity, so they settled dozens of new, illegal outposts. You will see them on every hill.”

Levy describes how a new outpost is established. “They begin with one or two tents. They bring a few cows or sheep, and then they confiscate the whole land around them.” The settlers “just take over, and nobody is there to stop them, and the army is even collaborating with them”, he says.

Its subscriber numbers may be modest, but in terms of influence Haaretz punches above its weight

By now we’ve left Route 5 and are heading northwest on the road towards Nablus. Chopin has displaced Beethoven on the radio as Levy points out the many metal gates at the entrance to Palestinian villages, which are frequently locked by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) at apparently random times, so that any Palestinian travel plans become unpredictable, if not impossible.

Settler attacks—which Levy describes as “pogroms”—are at record levels, too: “There’s not one day that they [the settlers] don’t burn a car, burn fields, burn olive trees, burn houses, and from time to time, they also kill shepherds and others. We did so many stories recently about people who were beaten. Last week, we did a story about an 81-year-old man who was beaten on his head by the settlers.”

We pass through one of several checkpoints. At first Levac suggests mounting a large PRESS sign on the dashboard, but thinks better of it.

“The final thing that’s dramatically changed is the policy of the army,” continues Levy. “Every Palestinian will tell you that the soldiers are not the same [since the Gaza war].” They have become more “brutal” and “cruel”, there are more checkpoints “and the collaboration between the army and the violent settlers became a reality, not an exception”.

Levy, who has been with Haaretz since 1982, says that most of this goes uncovered by much of the Israeli media. “I cannot watch TV anymore. It’s all the time only about hostages, families… soldiers, nothing else.” Settler violence, on the other hand, is only covered within a “framework of confrontations between settlers and Palestinians”.

We drive past the entrance to Tulkarm, a city of around 65,000 residents. The metal gate on the approach road is locked.

“The West Bank is now a lawless place, unbelievable, and no Israeli knows anything about what’s going on here,” says Levy, “The world is so preoccupied now with Gaza that this is forgotten.”

In a layby, we meet Abdulkarim Sadi, a 62-year-old father of four who is the northern West Bank field researcher for B’Tselem, the Israeli human rights NGO. He’s worked in the area for 39 years, 24 of them with B’Tselem.

Levy has brought some beer for Sadi, who has been up since 6am harvesting his own olive trees and promises to reciprocate with some olive oil the next time they meet. In English, they exchange pleasantries about the recent wedding of one of Sadi’s children and then we head up the hill to Anza to find out the truth about the killing of Ahmed Barahmeh.

In 2011, the New Yorker editor David Remnick described Haaretz as “easily the most liberal newspaper in Israel and arguably the most important liberal institution in a country that has moved inexorably to the right in the past decade”. In the 14 years since, the centrifugal forces in Israeli society have intensified. Haaretz has arguably become more leftist as the country has moved further to the right. Equally, the newspaper has become even more important.

Its subscriber numbers may be modest (135,000 across print, digital and its English-language and business sections), but, in terms of influence, it punches way above its weight. It is closely read as much by the liberal Jewish diaspora as it is in embassies and ministries around the world. Channel 12’s Amit Segal, a right-wing political pundit, recently declared that Haaretz.com, the paper’s English site launched in 1997, was the “number one threat to Israel’s position in the world”.

His reasoning was that Haaretz has negative things to say about Israel—its politicians and the way it has waged war—and “the people who don’t like Israel get the perfect excuse… because it was published in Israel itself”. By way of example, Segal said Haaretz makes claims along the lines of settler violence being “ten times more than” Palestinian violence in the West Bank “where the reality is that the Palestinian violence is a thousand times more than settler violence”. (While it is true that violence is at record levels in the West Bank across the board, UN figures show 34 Palestinians injured for every Israeli in the West Bank since October 2023; and a ratio of 16 Palestinians killed for every Israeli.)

A single fact-free sentence from the leading political commentator on Israel’s most popular television channel tells you much about the country’s media landscape.

Segal’s remarks also offer a glimpse into Israel’s bitterly polarised information war—domestically and internationally—throughout this period. The country is still processing the loss and grief of 7th October, which has continued with the plight of the hostages in Gaza.

“Self-censorship” has been the key trend, Oren Persico, Israel’s leading media analyst, tells me. “A lot of the journalists in Israel think they’re first and foremost Israelis and then journalists, and the job is to help Israeli society recover from the very real trauma of October 7th.”

“And then we have Haaretz. They’ve been publishing the pictures that all other media outlets don’t want to show you—front page, day after day. Their weekly supplement has a cover story about famine, and then another one and another one. They’re putting it in your face. And, you know, the other side says that it is helping the enemy convince the world that Israel is committing war crimes and thus is treacherous.”

In 1935, Salman Schocken, a successful Jewish department store owner, purchased Haaretz, having moved to Mandate Palestine from Nazi Germany. In 1939, he put his son Gustav (also known as Gershom) in charge of the newspaper. In 1940, Salman and his wife made a new life in New York. In 1945, Schocken Books, the imprint he had established the previous decade in Berlin, and which he had also relaunched in Tel Aviv, started publishing in the United States. Hannah Arendt was an early editor.

Salman died in 1959 and Gustav edited the paper for a remarkable 51 years before his own death in 1990. In 2014, a court in Berlin awarded €50m to the surviving Schocken heirs in Israel as an act of reparation for Nazi crimes against the family.

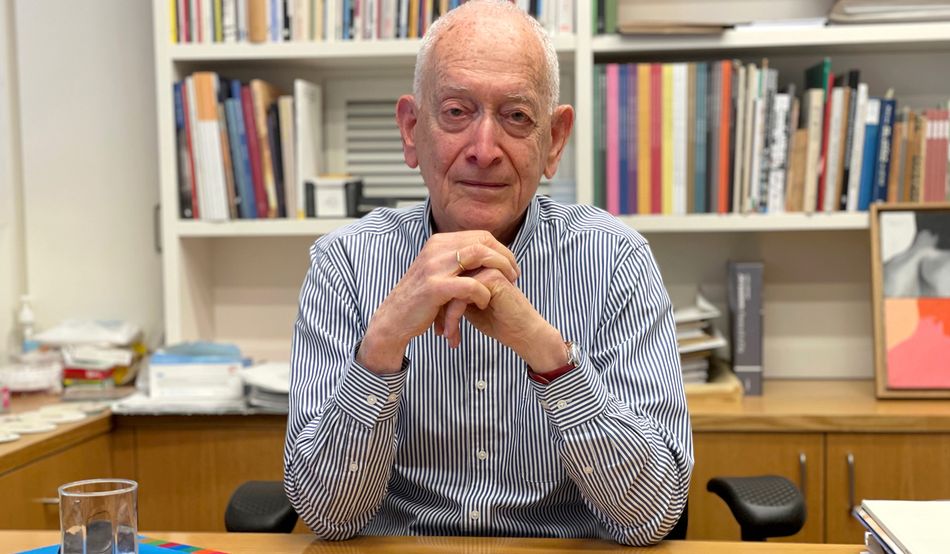

Gustav’s son Amos, now 81, became CEO of the newspaper in 1973 and has been running the show ever since his father died. Initially, he confined himself to the business side of the paper, but in more recent years he has been writing signed articles and helping oversee the paper’s editorial line.

When we meet in Tel Aviv in October, he tells me about the family’s history in his modest office in the Haaretz building on Schocken Street—unremarkable premises which are like any other newspaper office, but for the publisher’s extensive personal collection of modern art which adorns nearly every wall. Schocken’s desk faces an enormous canvas by the Palestinian artist Durar Bacri entitled Self Portrait with a Goat.

Tall, lean and softly spoken, Schocken is the opposite of the stereotypical dynastic media baron. His politics are, if anything, to the left of the paper. He has taken hard-headed business decisions in his time, but today he is keener to talk about Haaretz’s voice in the debates about Israel’s future. When that voice leads readers to threaten to cancel their subscriptions, he has been known to gently advise them that perhaps Haaretz is not a paper they should read.

‘They called us “the newspaper of Hamas”. But other people tell me it’s only because of Haaretz that they can still live in Israel’

I ask him if he has, as with so many Israeli journalists, felt a conflict between patriotic duty and the paper’s often vehement opposition to the way the war in Gaza is being prosecuted. He shrugs. “But you have no choice. I mean, if you want to do the job of a newspaper, you have to give your readers as best a description of reality as you can. Otherwise, you are not doing what you should do.”

He cites Levy’s work in sparse sentences: “It’s so important because no one else is doing this. You cannot ignore your neighbours.”

Schocken himself wrote a column a few weeks into the war, arguing that the only way Israel could retrieve anything hopeful from the massacre of 7th October was to get the hostages back and establish a Palestinian state. “It didn’t help so far,” he adds drily.

A fondness for speaking his mind landed Shocken in trouble towards the end of 2024 when, during a speech at a conference organised by the newspaper in London, he called for sanctions against Israel, accusing it of carrying out a second Nakba (the Arabic word for catastrophe, used by Palestinians to describe their dispossession in the war that established the state of Israel). “The Netanyahu government doesn’t care about imposing a cruel apartheid regime on the Palestinian population,” he said. “It dismisses the costs on both sides for defending the settlements while fighting the Palestinian freedom fighters, that Israel calls terrorists.”

Prime Minister Netanyahu responded by pulling all government advertising from the paper, citing not only Schocken’s speech but also “many editorials that have hurt the legitimacy of the state of Israel”.

Schocken tried to clarify his remarks, insisting that Hamas were not freedom fighters and pointing to Palestinian freedom fighters who were not terrorists. An editorial in his own paper gently chided him. A significant fellow shareholder in Haaretz, the Russian former oligarch Leonid Nevzlin, went further, taking to X to denounce the remarks as “appalling, unacceptable and inhumane”.

Regarding the criticism from his own team, Schocken seems unconcerned. “It’s not the first time that they’ve written against me. The chief editor’s opinion is always accepted as more relevant to decisions than my opinion.”

He was clumsy in his wording, he agrees, but says he is old enough to remember the Algerian civil war. “The truth is that these people, at some point, are forced to go to terror. It’s not a hunger strike that will get rid of the colonial power.”

And he has seen it all before. “It doesn’t make me lose sleep. They called us ‘the newspaper of Hamas’. But other people tell me it’s only because of Haaretz that they can still live in Israel. I sometimes meet them in the street. So there are people who think that what we do is right.”

The West Bank village of Anza (population around 2,000) is some 20km southwest of Jenin. Abdulkarim Sadi guides us through the winding streets to the office of the mayor, Thaisir Sadaqa, who greets us in a bare room dominated by pictures of former PLO leader Yasser Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas, the 90-year-old Palestinian Authority leader. There’s a lingering smell of stale cigarette smoke.

Sadaqa tells us that the IDF had been driving into the village every couple of days of late and he has no idea why. News of their presence generally spreads rapidly on the local WhatsApp group. Most residents disappear inside—though the young sometimes throw stones which, even if well-aimed, bounce harmlessly off the army jeeps.

We walk down to the spot where Ahmed Barahmeh died and learn from Sadi, who has already been on a reconnaissance trip, that, at around 7.30am on 24th September 2024, four armed military jeeps drove into the village. Four soldiers occupied the home of a teacher and his wife and took up position in a second-floor attic. From the barred window, crouching next to the washing machine, a soldier could aim a rifle into the village street.

Barahmeh was, according to his parents, on his way to register for his second year of engineering studies at university in Tulkarm. He was with two young friends, who testified that the jeeps had, for the moment, disappeared.

Was he carrying a stone in case the jeeps reappeared? We may never know. Forty metres away, a sniper in the teacher’s attic took aim and, with a single shot, ended his life.

Levy scribbles away in his yellow notepad as Levac, dressed in a blue and white striped T-shirt, prowls around with his old Fuji camera, recording the spot where Barameh fell—in front of a telegraph pole now adorned by a memorial photo of a “martyr”.

The plaintive call of a muezzin drifts over the rooftops as we drive up the street to meet Barameh’s grieving family at their home on the outskirts of the village. We sit on plastic chairs outside their house to speak with his mother, Fatma, 50, an education inspector, and his father, Jihad, 57, a retired transportation tester. Alongside them is Ahmed’s brother, Mohammed, 30, who has been working as an engineer in Dubai.

We are told about a young man keen to make his way as an engineer. A shy man who blushed easily and who took no more than an average interest in politics. Mohammed, who has been holding his mother’s hand as she dabs her tears, produces his phone to show a photo of his brother riding his horse, Ra’ed. We jot down details of Ahmed’s two sisters, one a physician, the other a pharmacist.

Levy, in a black T-shirt and sandals, knows little Arabic (“I tried everything, two teachers, even lived with a Palestinian woman for two years. Never made it.”) but listens intently as Sadi translates. His pen scribbles away.

Mohammed and Fatma retell the story of the morning Ahmed was shot. From the accounts they have been able to piece together, there were only three people in the streets when he was killed. “Usually, there’s some action, but on this day it was peaceful. There was nothing to throw stones at,” says Fatma. She holds her hands up in impotent despair: “They do whatever they want.”

The family seems honoured that a renowned Israeli journalist and photographer should have made the journey to record the life and death of their son. There are more tears and warm handshakes as we leave.

As we drive back towards Tel Aviv, Levy predicts how the IDF will respond to his queries about the story. “I know it by heart, even before I send the questions to them. They will say there was a lot of unrest here, Molotov bottles and who knows what. It’s the same story every time, full of lies. They never admit anything… The killing of a young man for nothing should be a story, for God’s sake, even if it’s daily, and it is daily… It’s almost, for me, a boring story because it’s so routine.”

His column—a straightforward factual account of the morning Barahmeh was shot and killed—appears a few days later. He quotes an IDF spokesperson: “A terrorist threw a device at forces from the Paratroopers’ recon unit… The forces responded with fire and eliminated the terrorist.”

I asked the Times of Israel reporter why the headline on his three-paragraph live blog entry accepted the IDF explanation without questioning it. He admitted that “it was a mistake”.

One commenter under Levy’s article wrote: “Such a very great achievement, Mr and Mrs Barahmeh. Four children so highly educated. It must have taken a great deal of effort, love and sacrifice. So very sorry.”

Another added: “Is it any wonder the world, after reading story after story of this kind of thing, no longer has any respect or sympathy for Israel?”

On the journey back to Tel Aviv, we pass through more checkpoints where Levy cheerily fibs that we have been visiting a settlement. I ask if he ever speaks to the settlers. “I try to avoid it as much as I can. I’m very afraid of them. They are extremely violent, and some of them are disturbed people.” Sadi nods in agreement.

What kind of abuse does he receive for his columns and his, now much less frequent, TV appearances? “The usual stuff about self-hating Jews. They used to give me a bulletproof car, but now it’s just stone-proof.”

Levy has been accosted in the street for his work. “I go jogging in the park every morning, and recently there was a woman every morning, six o’clock in the dark, and she screams at me ‘TRAITOR!’ I never saw her face because she runs much faster than me.”

He points out another Israeli flag on the ground, with a tent. “There will be somebody living there with his sheep.”

Musing on what he calls the “experiment” of Gaza, Levy says, “What did we think—that we will put them in a cage for 20 years, and there will be no October 7th?… They say, ‘you justify terror’. I don’t justify terror. I hate terror. Let’s call it an experiment in human beings. You put them in a cage for 20 years, and then see what kind of mutations will come out.” The only surprise, he adds “was obviously the unbelievable fiasco of the army” that day.

When he attends regular editorial meetings, he says, he and Amos Schocken are among the most radical voices. “For example, we both believe in sanctions; the others wouldn’t.” He says Schocken is still a Zionist—“Jewish supremacy between the river and the sea… there’s no other way to define it, but he’s also very liberal.”

We are now on the outskirts of Tel Aviv, and Levy points out a large, ominous building that could be an Amazon distribution centre but which he identifies as the Mossad headquarters. He advises against taking a photo.

Levy doesn’t describe himself as anti-Zionist. He prefers “non-Zionist”. “I can’t commit myself to supremacy of any kind. My fight is against apartheid and occupation, that’s my main struggle.” Still, in Israel, he says, “If you say you are not Zionist, it’s suicide. It’s like saying you’re not a communist in Soviet Russia. It’s outrageous.”

The next day, I tell the story of our trip to Oren Persico, the media analyst, over a morning coffee in Dizengoff Square. A display of hostage pictures, placards, candles, flowers and flags has taken over the centre of the place. Persico, an intense, bearded 49-year-old with round horn-rimmed glasses, has been writing about the Israeli media since 2007 for the Seventh Eye, a small, independent investigative magazine. His own politics are on the left of the Israeli spectrum.

He says Haaretz readers may not read Gideon Levy’s column very much—”It’s really the same story every week”—but they want to support a newspaper that runs it.

Persico gives me a primer on the rest of the media landscape and the way in which, since 7th October, the main discourse in Jewish-Israeli society is between the extreme right-wing and the centre-right. This followed a period in which, he says, Netanyahu’s long-term strategy had been to control the media: “He’d get a multi-billionaire to buy media, make a new media outlet, or if he can’t do that, insert megaphones for his messages in the newsroom.” Channel 14, in particular, operates as what Persico calls “a complete propaganda machine, loyal to him personally and not to some sort of right-wing ideology.” The station’s controlling shareholder is Georgian-born billionaire Yitzchak Mirilashvili, the son of a Russian oligarch.

The newspaper can report as freely as it does because Amos Schocken, its publisher, has made plain his own liberal worldview and support for Palestinian statehood

On Channel 14, “You can see them say things like, ‘I love the photos of crumbling towers. I have to see more crumbling buildings in Gaza in order to get my sleep.’ And things like, ‘There are no innocent people in Gaza, there is no hunger.’ There was an awful scene where they ridiculed a mother of a child that died from hunger, claiming that she is obese, she stole her child’s food, maybe she ate the child? Really grotesque sentences that you would imagine you could hear in a beer basement with drunken troops coming back from the war fronts. But it’s all nice ties and in a studio, it looks like a news operation.”

It is, Persico says, really left to a few alternative media outlets, and Haaretz, to cover what has been going on in the West Bank, or to report on the scale of the deaths, famine and destruction in Gaza. I ask him why in his view so many professional journalists have chosen to ignore the “other side” of the war. He pauses for thought and sips his coffee. “Israeli journalists are really a part of Israeli society, right? They go into the army. They know people who died on 7th October or were wounded, or their community was ransacked. It’s a very small country. They have real trauma, real trauma.”

From an outside perspective, he tells me, “7th October might look like peanuts” compared with what Israel has been doing in Gaza. “But for Israel, it goes very deep, to the Holocaust trauma, to the very ethos of the State of Israel, so that Jewish community unity would never be burned to the ground again by enemies of the Jews. That is the reason we’re doing all the horrible things, right?”

It is difficult, he adds, for an Israeli journalist “to step out of this artificial comfort zone—the bubble that is surrounding Israeli society—and decide to do something about it. It’s wrong, it’s unprofessional. It’s not just avoiding your call as a journalist; it’s also amplifying calls for incitement and war crimes. The Israeli media did a horrible job. But I can understand why they made those choices”.

Later that day, I meet up for another coffee with Uri Weltmann, the 40-year-old national field organiser of Standing Together, the largest Arab-Jewish grassroots movement in the country, and another left-winger. He tells me of a “shaking experience” in May when he visited the UK and found people “far better informed about the reality in this land than people who live an hour’s drive away” from the atrocities on the other side of the border.

He says that, for example, when the Israeli media reported on starvation in Gaza, “the framing of these reports was not ‘there is starvation in Gaza’. It was ‘how should Israel’s government or diplomats counter these claims?’ So, the world sees one picture about what’s happening in Gaza, and we Israelis are being presented a different picture.”

I put to him the argument that the British people didn’t have much empathy with German civilian deaths during the Second World War. “Well, I think this analogy is lacking,” he says. “Hamas rule in the Gaza Strip is not a militarised industrial superpower like Nazi Germany was at the heart of Europe in the 1930s. A far better analogy would be to compare the way UK media reported on the realities in Iraq and Afghanistan in the early 21st century, when UK troops were part of the US-led war in Afghanistan in 2001, and in Iraq in 2003.” Newspapers that reported on atrocities suffered by Iraqi civilians were not branded “‘Saddam apologists’ or ‘al-Qaeda supporters’”, he says. They were seen as doing their journalistic duty, reporting what the British army was involved in.

“Israeli media doesn’t report the lived reality of Palestinians in the Gaza Strip,” he adds. “It doesn’t even truthfully report the lived reality of Palestinians in the West Bank. The West Bank is not Hamas-dominated, and the West Bank did not launch a surprise attack on Israel on 7th October 2023. Yet you won’t hear in Israeli media about, for example, the daily settler attacks on Palestinian villagers; setting fire to agricultural crops and to homes and cars; beating Palestinians, sometimes shooting them to death, all with Israeli army soldiers standing idly nearby, sometimes participating and giving backing to the violent settlers.”

He says Haaretz can report as freely as it does because Amos Schocken, the publisher, has made plain his own liberal worldview and support for Palestinian statehood. “His journalists know he’s got their backs—and that allows them to practise journalism in a way that’s truthful and rounded.”

A similar view of how the majority of Israelis have effectively chosen not to see Palestinian suffering came from Dahlia Scheindlin, a respected pollster and writer (with a regular column on Haaretz.com). She cites how so many Israelis managed to convince themselves that reports of famine in Gaza, circulating globally, were inaccurate: “You have masses of Israelis who were prepared to believe that it was all a Hamas PR campaign, because they had not been seeing the buildup of this situation of famine all of that time. ‘They’re all against us’ was the subtext. The ‘negative reporting about Israel’ gets plenty of coverage. What doesn’t get coverage is the situation in Gaza.”

She accepts that, in wartime, it is not unusual for countries to prioritise their own narratives, but feels that most of the Israeli media was “denying the Israeli public the information that could ever penetrate their sense that they alone are the exclusive victims, and by definition cannot be perpetrating any of… the war crimes that Israel is accused of”.

You don’t have to look hard for a contrary view of Haaretz’s role in Israeli life. Haviv Rettig Gur, 44, a senior analyst at the Times of Israel, and on the centre-right of Israeli politics, is one of them. On his podcast in June, Rettig Gur was dissecting a bombshell Haaretz revelation that Israeli soldiers had reportedly been deliberately shooting and killing civilians at food distribution centres in Gaza: “Haaretz sets itself up as an iconoclastic plastic elite kind of cultural institution in a country that it perceives as not elite enough.”

Referring to the various ethnic groups in Israeli Jewish society, he continued, “Sometimes that means ‘not Ashkenazi enough, far too Middle Eastern and not liberal enough and not democratic enough and not literate enough’, and therefore Haaretz is going to be the moral conscience of a country too ignorant and backward to have the kind of moral conscience that good, well-spoken and well-read Ashkenazim have. They say it: ‘We are a liberal, western, well-read, scholarly, thoughtful elite, which is why we’re very left-wing.’”

“Haaretz has, therefore, a duality. It has some of the most indispensable journalists in Israeli journalism because they are iconoclasts, because they are opposed to the mainstream as their sort of vision of themselves. They get their validation from turning over the rocks and finding the dark places and finding the things that other journalists are uncomfortable looking at or literally would never think of looking at.”

Rettig Gur went on to critique the “completely ridiculous, ideological capture, partisan framing” in the food queue story, especially in Haaretz’s English-language edition. He conceded the reporting was accurate but accused the paper of presenting it in a way that was driven by “an addiction to appealing to international progressive politics”.

I sought another view from Professor Yedidia Stern, 70, a religious man who describes himself as an Orthodox Jewish centrist. He is the president of the Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI) in Jerusalem. In common with other interviewees, he agrees that, for the past two years, the suffering of Palestinians was not mentioned, described or visualised for the overwhelming majority of Israelis through their country’s mainstream media.

He considers that Haaretz performed a “very important service” in swimming against the tide—”the only [mainstream] outlet that was doing it in a very serious and ongoing way, sometimes in an exaggerated way.” He has, he says, been reading Haaretz since he was a kid.

“I raise my imagined hat to them because obviously you’re losing ground in Israel today when you do that. If you care about the financial aspects of your paper… knowingly hurting its financial prospects because of ideology or because of what they felt” is for the greater good.

I ask him for examples of how the paper might be deliberately acting in an uncommercial way. “I could give you many—for example Gideon Levy ongoing every week, almost a whole page describing the suffering of the Palestinians, mainly in Judea and Samaria [the name given by the Israeli government to the West Bank, drawn from the biblical name for those regions], week after week, like a crusade, when obviously Israelis do not want to read it,” he says.

“It is not my cup of tea. First of all, it’s boring, because you know what you will read, but it’s so important because this should be on the agenda of everyone who is humanistic.” For good measure, Stern adds: “The same thing on the other side. For the last two years, all Israeli media is telling the stories of the hostages. I understand why. I respect it, it’s an expression of solidarity between us. But, you know, it’s repetitive. It’s not new.”

He reaches for a biblical parallel. “There are two kinds of prophets. One is Amos and the other is Jonah. Amos, whatever he says about the society he lives in, you feel he is totally part of it. He’s not talking about somebody else. He’s talking about his people. Jonah… runs away, he escapes, and when he’s being pushed by God to give his prophecy, which is again critical of society, he’s doing it from away; I’m looking at you and I’m telling you what I see wrong, but I’m staying out of it now.’”

Sometimes, he says, Haaretz behaves like Amos. “But sometimes I feel—and I think many Israelis feel this way—Haaretz is behaving like Jonah.” He cites Amos Schocken’s remarks about freedom fighters. “First of all, I adore that he can say it against all his interests, but I feel he is Jonah. Sometimes when I read Haaretz, I feel punched in my face.”

The day of my main visit to the Haaretz office, 9th October, coincides with the news that some sort of ceasefire in Gaza is imminent. The mood in Hostage Square, another locus of post-7th October activity in Tel Aviv, was one of nervous relief rather than joy. There had been too many false dawns for anyone to start unbridled celebrations.

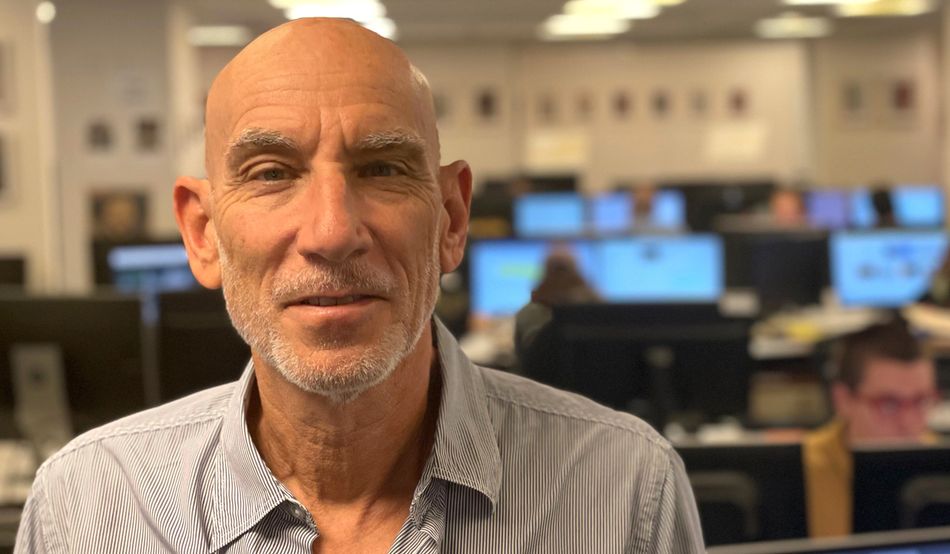

In the newsroom there’s a busy hum. Aluf Benn, editor-in-chief, seems impervious to any tension as he strolls around the office in his open-necked shirt and jeans. He’s worked for the paper since 1989 and has been editor for 14 years. He’s seen truces come and go. We settle down in his modest office and Benn, 60, rattles through his biography. He’s the son of a poet and teacher and thinks of himself as “pretty much as part of the old establishment here as can be”. The family were close friends with the family of former prime minister Ariel Sharon, who led Israel’s abrupt and unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip in 2005.

His military service was “nondescript, unimpressive”. As a young reporter, he did a big investigative piece into the Nakba, specifically how Israel expelled the Palestinians from what is now Ashkelon, but was the Palestinian town of al-Majdal. Such things were rarely written about in the Hebrew press at the time.

Since joining Haaretz more than 35 years ago, he’s done it all—covering defence, foreign relations, national security, working as an editor across news and comment and as a columnist. He knows he is walking a tightrope in terms of how much his readers will tolerate the newspaper giving them its version of the unvarnished truth about the West Bank and Gaza. “When we publish reports about starvation in Gaza, or pictures of Gazan children killed by the IDF, a strong contingent of our own readers doesn’t like it,” he says.

We talk about the dilemma of being both an editor and a patriot. I tell him that when the Manchester Guardian vehemently opposed the conduct of the Boer War and revealed the use of farm-burning concentration camps, its staff needed a police escort to work. Circulation fell by 15 per cent, but the editor, CP Scott, said that opposing the war was “the best thing that the Guardian has done in my time”.

Benn tells of how his own staff and their families had been affected by the 7th October massacre in southern Israel. “Many had friends, classmates, cousins, either killed or kidnapped. So we felt it. It hit close, close to home.”

Nevertheless, the first editorial Benn wrote the day after Hamas’s attack pinned much of the responsibility “squarely on Netanyahu’s shoulders and his pre-war policies, and his ignorance of warnings… even then it was clear where it was heading”.

There was criticism of running the story in which Israeli soldiers talked about shooting at food queues. “Government ministers all blamed us for assisting Hamas, but nobody was able to refute it.” Does he understand the criticism that Haaretz is out of touch with the “real” Israel of today? “I never understood what it means—that we don’t follow the lead of the mainstream?”

Benn tells a story of how, in his view, it is the “mainstream” that has changed. In 1983, an 11-year-old Palestinian girl, Aisha Bahash, was shot and killed by a settler in Nablus. It led to the conviction of Yosef Harnoi, the shooter. “This was every day in the news and was discussed in cabinet meetings and so on. Today people are more oblivious about the settlements and the West Bank because it’s less reported. People don’t care about that. All of those people of the ‘real’ Israel, as you want to call them, they just don’t care. And I think that’s one thing that helps Netanyahu to stay in power. So the destruction of Gaza and mistreatment of Palestinians in general are very popular with Israeli Jews.”

He speaks admiringly of Amos Schocken as someone who shields the newspaper’s journalists from its directorial board. “We are still pretty much immune from whatever is happening on the top floor. Amos one day told me that in the dilemma between, ‘should we publish or not publish?’, the default option is to publish.”

What of Benn’s decision to criticise his own proprietor in an editorial? “What you see is the rare publisher who is willing to accept this dissent and just move on.” Benn says he’s unsurprised by the strong reactions provoked by Levy (and also by another famous, to some infamous, correspondent, Amira Hass, a “world-class reporter” who has lived in both Gaza and in the main West Bank city of Ramallah). “It’s much easier to get angry at someone who speaks your language and knows exactly what buttons to push.”

Levy’s Twilight Zone column “gives voice to the occupied and that’s a crucial part of the story that, again, mainstream Israel couldn’t care less about. All it wants is for the nuisance to go away. It doesn’t want the conflict. It doesn’t want attacks. It doesn’t want to hear about it… The fact that Gideon goes there week after week, to the most distant places, is remarkable”.

“I am among those who believe that the defining story of this place is the conflict. You need to tell that story even when your audience oftentimes doesn’t want to hear about it. We’re not doing it for the traffic.”

On 7th October 2023, Nir Hasson drove south towards the site of the Nova festival, where nearly 400 young people had been massacred. The 50-year-old staff reporter saw bodies all around, met countless people, spent time with relatives in hospitals.

He then concentrated on covering one kibbutz in southern Israel, Nir Oz, of which his father had been a founder and which suffered unimaginable loss that day. “The people told their stories, and every person that you sit with has an unbelievable story. It was really crazy.”

Around June or July the following year, the death toll in Gaza was approaching 40,000, and Hasson asked to be transferred to covering the humanitarian situation in the Strip. For the next 18 months, he concentrated on telling the stories of Palestinians there.

“I start watching thousands of videos coming out of there, which are—there’s no words to describe it, right? It’s like you see bodies in all shapes, parts of people. You see human suffering in all its forms. And then I start talking to people in Gaza. First, it was mostly UN and humanitarian organisations, but later, with many doctors who work there and with many Gazan people, we found out that they’re willing to talk to us. And I published, I don’t know, dozens and dozens of articles and some big investigations about what’s going on there.”

In December 2024, he published a major investigation into thousands of war crimes committed by the IDF and documented by a Jerusalem-based historian, Lee Mordechai.

‘Mostly what I write is about the starvation, the displacement, the killing and destruction’

“It was shocking. It was the first time we were saying, ‘Okay, actually, the IDF is committing countless numbers of war crimes in Gaza. It was all from open sources: he wrote a report with thousands of links, some of them just horrific to see.”

Hasson—solidly-built, in an open-necked checked shirt and chinos—sits rubbing his glasses as he recalls the death and injury he has seen on both sides in the previous two years. “Since then, this is what I do… mostly what I write is about the starvation, the displacement, the killing and destruction.”

Why is it so important to report these stories? There is a long pause for thought and he then speaks carefully and deliberately. “I think what’s going on in Gaza in the last two years will shape our future.” He believes that Israeli atrocities in the Strip have shattered “the foundation of the State of Israel”, not only in terms of the country’s legitimacy on the world stage but also “unity” among Israelis. “It’s destroyed both of these foundations.”

These two years have not only changed the way Israel is seen internationally, but have linked the country to the perpetration of genocide, he says. “And it doesn’t matter if I think there is genocide in Gaza or there is not. It doesn’t even matter if the ICJ [International Court of Justice] will decide, in a few years from now, that there was a genocide in Gaza. What matters is that the war in Gaza will be the perfect case study for scholars all around the world for this question: ‘Is it a genocide or not?’ What matters is that people in Europe and all around the world will see it as a genocide.”

Hasson “cannot think about anything more important” than the fact that his country and government are “responsible for what many people around the world see as a genocide. Now this is not the real disaster. The real disaster is the tangible death of the people in Gaza. But for the future of my children, for the future of this place, we have to know it. We have to know that that’s what’s going on now”.

Like other interviewees, he believes that the average person watching the news in the UK or the US knows more about what’s happening in Gaza than the average Israeli. “Which is crazy. We are not talking about it… and I take part of this responsibility. I didn’t talk about it for the first few months.”

In 1982, he notes, when up to 3,500 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon were killed by a Christian militia in the Sabra and Shatila massacre, with Israel believed either to have turned a blind eye or supported the violence, 400,000 people demonstrated in Tel Aviv. Today only a small minority protest against the violence in Gaza.

“This indifference to killing so many people, it’s a new thing in Israel. Part of it, of course, it’s the 7th October trauma. I can understand it. I can relate to it. I saw the bodies. I’ve been there. I know the pain. I know the people from Nir Oz. But it cannot be the only explanation. I think of years and decades of shifting to very extreme politics; of becoming a more religious society with corrupted leadership; and, most importantly, the dehumanisation of the Palestinians. Because it’s unbelievable that we could kill 20,000 children in Gaza and nobody speaks about it.”

Hasson has been a staff reporter for Haaretz since 2008, covering Jerusalem, archaeology and major news events. He served two years as deputy news editor. Somewhat to his surprise, he received the 2025 Sokolov Prize, Israel’s most prestigious journalism award. The judges said, “He has consistently and systematically given a voice to a population that most journalists in Israeli media avoid covering.”

His was one of three bylines on the June 2025 story in which IDF officers and soldiers told Haaretz they were ordered to fire at unarmed crowds near food distribution sites in Gaza, even in the absence of any actual threat. At the time, hundreds of Palestinians had been killed at the sites, prompting the IDF’s military prosecution to call for a review into possible war crimes. (Netanyahu responded by calling the story “blood libel”, the antisemitic trope accusing Jews of ritualised murder.)

But Hasson is equally proud of his work as one of two reporters who set out to investigate whether the stories of famine in Gaza were—as the Israeli government and much of the media claimed—a piece of Hamas spin or antisemitic propaganda. Netanyahu had threatened to sue the New York Times for defamation over a photo of a skeletal child published without mentioning a pre-existing medical condition. Stories of starving children were, the prime minister alleged, also blood libel.

Nir and his colleague Yarden Michaeli called dozens of doctors in Gaza and asked them to open Zoom and take the reporters on a virtual tour of the places where they were treating children. “It was crazy. Really, the condition of the kids there…” His voice tails off.

“And we published, I think, 30 photos. We had a database of children, most of them with extreme malnutrition. There was almost no response to this investigation, because people could not argue with it. I mean, it was clear that there was famine in Gaza.”

I ask him whether Israel is still a fact-based society. “Oh, it’s a very good question. It’s not anymore. I don’t know how bad we are compared to other countries, but I think we are in a very bad situation. I remember my father every night, sitting in front of the news with one channel. He sees the news, and then in the morning he will argue with his friend about the news—but they still had the basis of the facts that they could argue and bring their values. But today, if you see Channel 14, you live in a very different reality than if you see Channel 12, or if you read Haaretz. It’s like bubbles that do not meet.”

I speak to two more Haaretz reporters that October day, as an end to the Gaza war hangs in the balance. One, Sheren Falah Saab, 38, is Haaretz’s Arab affairs correspondent, recruited as part of a scheme piloted by deputy editor Noa Landau to employ more Arab-Israelis (around 2m Arabs make up around 21 per cent of Israel’s population; the vast majority of them identify as Palestinian).

Saab lives in the north of Israel and comes from a Druze background. She has spent much of the past two years using her contacts in the Strip to “try to bring a sense of humanity back into the conversation… It’s very emotional. I’m part of Israeli society. I also have friends who were kidnapped or killed on 7th October. But on the other hand, I have friends in Gaza who have had to leave their homes, who have been under bombing, and who have no safe space. Sometimes I feel that I’m walking in a very thin line between journalism and being human.”

She says she no longer has the patience to consume Israeli media because of the “alienation” of Palestinians. “For many Israelis, Gaza doesn’t exist: it’s like a black hole in their mind.”

‘These two years changed me as a journalist. I don’t think that you can write about Gaza and stay the same person’

Saab’s particular focus is on children and women in Gaza. How they deal with their daily lives, for example when they give birth or are on their period. “There is also sexual harm for women. There’s a lot of pressure if you’re a mother and you want to bring food for kids and you don’t have a husband because he’s been killed during a bombing. So, as women, you have to do something. So there’s a lot of pressure.”

A little while into our conversation, Saab starts to weep. “These two years changed me as a journalist. I don’t think that you can write about Gaza and stay the same person. I carry the stories with me every day. You know, it’s not just about Gaza. It’s about what it means to be human in a time of collapse, how to be a journalist during the collapse of humanity.”

Amos Harel, 57, is the newspaper’s chief military analyst. He has been writing about Israel’s army for more than 25 years and feels some of those tensions. “I’m pro-Israeli, I’m a Zionist and yet I’ve been constantly criticising the army for 20-odd years. But this felt different. In Israel, there’s one degree of separation, not six, as the Americans say. It’s still a collective PTSD that we’re suffering from, and we are very much focused on our own suffering and misery and hardships. And that meant that most of us could not spend so much time on what the other side’s suffering looked like. I think anybody in their clear mind would not deny the atrocities of 7th October. There were rapes, there were murders. I’ve talked to people who’ve experienced that.”

He’s aware of criticism that Haaretz’s focus on the suffering of both sides can seem relentless, but adds: “Who else is going to publish [this stuff] if it’s not us? I think investigative reporting is crucial. I sometimes have problems with specific headlines, particular editorials or op-eds and so on. I sometimes think the language being used by Haaretz is too distant from what is going on in the minds of the Israeli public. Tel Aviv’s left-leaning reality is somewhat detached from most of Israeli society, and I think there’s a potential problem there. But regarding the investigative stories, I think we need to print them. Nobody else is going to.”

Ever since William Howard Russell of the Times filed his devastating account of the Charge of the Light Brigade in November 1854, newspaper editors have wrestled with the dilemma of how to maintain objectivity and truthfulness in times of war.

Prince Albert fumed at how “the pen and ink of one miserable scribbler is despoiling the country”, while Sidney Herbert, secretary of state for war, stated: “I trust the army will lynch the Times correspondent.”

In March 1942, Churchill threatened to close down the Daily Mirror. The Guardian and Observer took lonely stances—subsequently vindicated by most historians—in their forthright opposition to the folly of Suez in 1956. I myself was hauled up in front of MPs in 2013 to answer the question ”Do you love this country?” after publishing uncomfortable revelations about how western powers were using technology for widespread surveillance.

Haaretz fits in that tradition of continuing to ask the difficult questions even when—particularly when—the overwhelming sentiment is to look the other way. If there had been no Haaretz during the past two years, where would that have left Israeli democracy—for those who believe such a thing still exists?

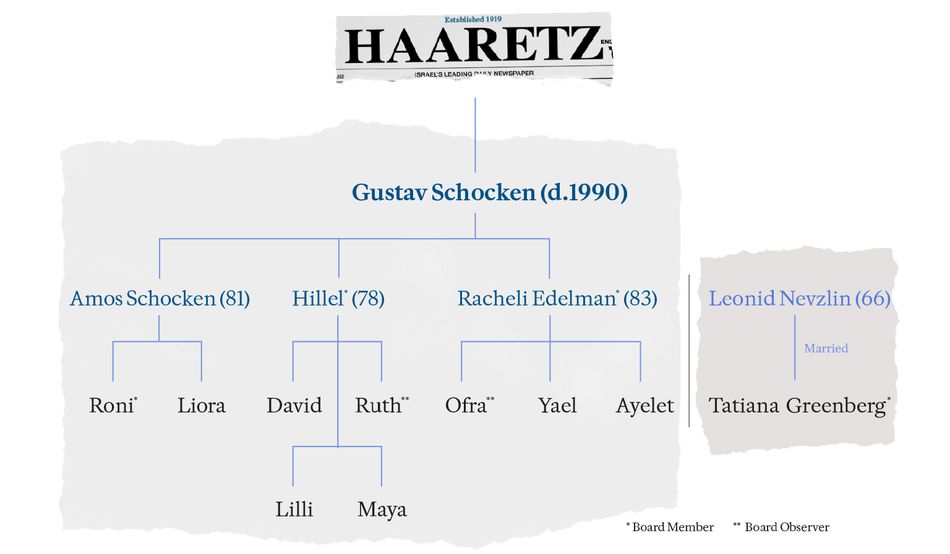

But love or hate Haaretz, it is extraordinary for one newspaper to have been run by two people, Gustav and Amos Schocken, for more than 85 years. What of the future? Gustav’s three children are now all advanced in years. There are nine grandchildren.

It is a private company, so it is hard to accurately assess the financial health of Haaretz. Amos Schocken told me he expected to report zero profit this year, adding: “In previous years, we were profitable, but the war cost us loss of revenue. I think we will be okay… our balance sheet is very strong. No debt.”

One board director insisted the picture was a little more complicated, with profits from the wider group (which owns other publications, including TheMarker business paper, as well as a number of publishing houses) subsidising the newspaper itself. Not quite right, said another board member. A “material growth” in digital subscriptions has meant that Haaretz has itself been profitable for some years, with a new CEO building a long-term growth plan.

The governance structure is complex, but worth understanding. There is a board of four: three Schockens and one outside investor. The chair is, unusually enough, rotated every few months. Amos has nominated his son Roni, a mild-mannered 43-year-old financial analyst settled in north London, as his representative on the board. His brother Hillel, a 78-year-old architect, occupies the second place; his sister Racheli Edelman, an 83-year-old publisher, the third. Two of Roni’s younger cousins sit as board observers. Between them, the Schockens own 75 per cent of the company.

In 2006, Amos Schocken sold a 25 per cent share in the group to a German publishing enterprise. In 2011 the Germans sold out and a 20 per cent stake was instead bought by former Yukos oil tycoon Leonid Nevzlin, who was convicted in absentia of several cases of conspiracy to murder in Russia, in what he terms a show trial. The reported price was $41m.

There have been various tensions along the way. The sibling relationship between Amos and his brother Hillel survived an investigation by the paper questioning the latter’s professional qualifications. And then, in February this year, Hillel’s son David published—in Haaretz, of course—a scathing attack on the paper his uncle leads.

“The one-sidedness of thought presented between the pages of the newspaper has long become a given,” the graphic designer wrote. “The newspaper’s readers know what will be written in it before they even open it, and people who are not part of the newspaper’s traditional readership feel that they and their positions are not represented with respect… the uniformity of thought has become so rigid that any position that deviates from it is immediately singled out for disgust and met with scorn.”

He continued: “Among the newspaper staff, there are also those who compete with each other in their degree of disgust for elected officials, the public that elected them, the values that guide their election, and every detail of the culture that is increasingly taking a place in the centres of power, instead of the representatives of ‘good old Israel’.”

If you are a fan of Succession, the Murdoch-inspired HBO drama series, think of Kendall Roy. Amos Schocken’s nephew David, in his mid-forties, sports a white Lytton Strachey beard, lives in the northern hipster town of Pardes Hanna and has also written—again, in Haaretz—about his refusal to vaccinate his children.

And then there is the complicated position of Nevzlin, reported to be worth more than €1.3bn at the point he fled to Israel in 2003. His denunciation of Amos Schocken’s reported “freedom fighters” remarks as “shocking, unacceptable, and even inhumane” was faithfully reported in Haaretz.

Nevzlin’s disagreements with the paper’s editorial line since the start of the Gaza war appear to go deeper, however. A reliable source told me he stepped down from the board in 2024 due to a fundamental disagreement over the paper’s coverage, dating back to 8th October the previous year. His place on the board was taken by his third wife, Tatiana Grinberg, a 47-year-old philanthropist and investor who left Moscow for Israel in 2010.

Nevzlin is understood to believe that, without significant changes, the newspaper has a very low chance of long-term survival. For now, with Amos Schocken in charge, all is stable. But, as in Succession, transition to the next generation of media moguls is often convulsive. “I’m sure it will get messy,” says my source. “I’ll sign on it.”

On the eve of the ceasefire deal announcement, I have supper with Haaretz’s editor, Aluf Benn, in Shila, a buzzing restaurant 15 minutes’ walk from the Mediterranean beach, itself little more than an hour’s coastal drive from Gaza.

He has been on a war footing for more than 730 days but, if he is feeling at all drained by editing Israel’s most controversial and consequential newspaper, he doesn’t show a trace of it.

Afterwards, he walks me back to my hotel, pointing out a handful of architectural gems and one building taken out by an Iranian missile just months earlier, during the 12-day Israel-Iran war.

So if covering war doesn’t faze him, is he kept awake at night by what might happen to the ownership of the newspaper, which has allowed such remarkable journalism to flourish?

“I know Amos’s brother and sister, I don’t doubt their commitment to the same values that the family represent. It’s 90 years that they have owned the paper. I really don’t doubt it. I think they share the same ideas about its importance and the value of independent journalism.”

But then, every inch the old newspaper hand who has to cover himself, he adds: “You can never know.”