“What are you doing here?”

It is a sunny April morning in Sheikh Jarrah, East Jerusalem, and a Palestinian man is busy on the roof of a low-set house. Under the partial shadow of a tree, it looks like he is fixing something, but Arieh King, one of Jerusalem’s deputy mayors, is suspicious. “My home here,” says the man. “This is not your home,” King replies.

Wearing the knitted yarmulke of Israel’s Religious Zionist right, with tzitzit—the knotted ritual strings worn by observant Jewish men—poking out under a light blue shirt and sporty black jacket, King is performing his authority in front of about 30 people, all standing awkwardly on the road. We are here for a tour that he is personally giving—and over Passover, a public holiday, mind you—for the Israel Land Fund (ILF), an NGO he founded which works to “redeem and purchase land throughout Eretz Yisrael [the land of Israel] for the Jewish people”. Its activities, the ILF website states, include facilitating the purchase of land and property by Jewish investors from non-Jews and from Jewish heirs, “assisting owners and tenants of Jewish-owned properties in strategic areas, including renovation, maintenance and escorting residents”, and giving “geopolitical information tours”.

The Palestinian man tries to explain that he does have permission to be on the roof. He mentions a Daniel, apparently the owner of the property. But this won’t do for King, who tries to get Daniel on the phone. By the time Daniel returns the call, we have walked around the corner to a cluster of ramshackle homes around a patch of grass, the centre of this embattled neighbourhood.

“Daniel, I passed your house where you live and on the roof there was this Arab hanging around there. He says this is coordinated with you?... Daniel, a brief question: Did he talk to you? Yes, or no?”

King left the ILF in 2021, shortly after he became a deputy mayor. Through this organisation, and since he became a Jerusalem city councillor in 2008, King has worked to evict Palestinians in East Jerusalem (a territory Israel occupied in 1967 and officially annexed in 1980, still considered occupied under international law) to make way for Jewish residents. Responding to a request for comment, King confirmed that he has worked “to return properties to Jewish hands” and “remove illegal squatters”. The deputy mayor has been active in other parts of the West Bank and inside Israel, too. He has done this in pursuit of a messianic, extremist Religious Zionism, which in recent years has moved from the fringes of the Israeli right to the centre of power.

Everything he does, King tells us repeatedly, is to bring geulah—the final redemption of the Jews from oppression, persecution and exile. And King, who was born in Israel to British parents and says he holds British citizenship, sees his very existence as part of this process.

“I was sent here because I am the tikkun [the Jewish concept of repair] of all of the damage that the British did to the Jewish people in Israel, in Jerusalem specifically,” he says that day, a reference to the 28 years that the British Mandate authorities administered Palestine. “I am really the tikkun.”

Sheikh Jarrah, the first stop on the Jerusalem tour, is one neighbourhood where King is well known. Activists often flock here, the site of a years-long dispute between settler groups and Palestinian families under threat of eviction, to protest the dispossession of Palestinian residents and their regular harassment and intimidation by Jewish settlers. At times the area has been the subject of global attention, even described as a “microcosm” of the conflict. King refers to it by the names of Jewish neighbourhoods—Nahalat Shimon and Shimon Hatzadik—that were located here until 1948, when the war that ultimately established the Jewish state began. As violence broke out, Mandate authorities had ordered Jewish families living there to leave for their safety.

On 6th May 2021, ahead of a decision by the Israeli Supreme Court on the eviction of six Palestinian families from Sheikh Jarrah, local tensions erupted into more widespread protests and then violence, which led to confrontation between Hamas in Gaza and Israel. The hostilities ended with a ceasefire two weeks later. King told the New York Times that evicting the families was part of a strategy of creating “layers of Jews” in East Jerusalem; this, King said, was “the way to secure the future of Jerusalem as a Jewish capital for the Jewish people.”

On the evening of 6th May, King was filmed in Sheikh Jarrah as Palestinian residents and activists were breaking their Ramadan fast. Standing with Bentzi Gopstein, a leading Jewish supremacist activist, and Itamar Ben-Gvir, head of the far-right Jewish Power party and now a government minister, King appeared to mock a Palestinian resident from another neighbourhood who had been shot in the back in a separate incident. “It’s a pity [the bullet] didn’t go in here,” King said, pointing at his forehead.

Nearly four years later, on that sunny morning in April, the region was yet again mired in terrible crisis. Some 50 miles away in Gaza, an 18-month war raged, relentless. A few weeks earlier, Benjamin Netanyahu had broken Israel’s ceasefire with Hamas. A blockade imposed since 2nd March was stopping aid and food from entering Gaza, pushing Palestinians there ever closer to starvation. The reported death toll would surpass 52,000 that month, according to Hamas’s health ministry, and some 59 hostages (mostly Israelis, but also some foreign nationals) remained in Gaza. Nearby in the West Bank, violence had been at record levels since Hamas’s 7th October attack on southern Israel. Israeli military activity there, ostensibly anti-terrorist, had displaced around 40,000 Palestinians, while settlers were harassing and attacking Palestinians with impunity. On 20th May, the UK announced sanctions against three settler leaders, two settler outposts and two organisations “supporting violence against Palestinian communities in the West Bank”.

We are told to expect nothing less than to witness “with your own eyes, the process of redemption, the process of rebuilding... Jerusalem”

Among the tour’s participants there is a holiday mood, however—carefree, cheery excitement. The participants are a mix of Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews, the women in wigs or colourful head coverings, and are mostly American and middle-aged if not elderly, save for a father and his three young sons in matching black and yellow baseball caps. The tour is in English—suggested donation 60 shekels (about £12). As we set out from the Olive Tree Hotel, we are told to expect nothing less than to witness “with your own eyes, the process of redemption, the process of rebuilding... Jerusalem”.

King has long pushed the “judaisation” of Jerusalem. He’s never been shy about saying so, whether from the municipality or outside of it. But since 7th October, the deputy mayor has ramped up his activity on another related matter: kicking UNRWA, the UN agency which supports Palestinian refugees, out of the Jewish state.

UNRWA (or the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) was established after the 1948 war, when Israel was founded and around 700,000 Palestinians were expelled from or fled their homes. Today, 5.9m Palestinian refugees living in the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria can access healthcare, education and financial support through the agency, though in practice it serves some two million people. UNRWA’s operations have been vital to getting food, aid and medicine to Palestinians since the war in Gaza began.

After 7th October, the UN agency was placed under intense scrutiny. The Israeli government alleged that Hamas had “systematically infiltrated” UNRWA, and that 12 UNRWA staffers (an estimate later increased to 19) took part in Hamas’s violence that day, in which 1,200 people were killed and 250 taken hostage—the majority of whom were civilians, including women and children.

In January 2024, various donors, the US and UK among them, paused their funding (the UK has been a significant benefactor to UNRWA, which is funded by voluntary contributions from donor countries; in 2024–25 the UK committed £41m). By July, following an independent review and UNRWA saying it would enact management reform, the UK restarted its contributions alongside France, Germany, the EU, Japan and other states.

“It is aid agencies who ensure UK support reaches civilians on the ground,” the new foreign secretary, David Lammy, told parliament at the time. “UNRWA is absolutely central to these efforts. No other agency can get aid into Gaza at the scale needed.” In August 2024, UNRWA said it would fire nine staffers allegedly involved in the attack.

UNRWA has long been an obsession on parts of the Israeli right

But in Israel hostility to UNRWA remained, culminating in legislation that severely limits the agency’s ability to operate. In October 2024 the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, passed two laws curbing UNRWA. (Both passed almost unanimously as opposition parties voted with the government; only Arab-majority parties voted against.) This legislation bans UNRWA from operating in Israeli territory and cuts ties between Israel and the agency. In practice, this makes any operation that involves contact between UNRWA staff and Israeli officials potentially illegal, from renewing visas to shipping aid through the country.

UNRWA has been an obsession among parts of the Israeli right for much longer. As early as 2016, King posted on Facebook calling UNRWA “antisemitic”, accusing it of violating city planning laws and urging the then-mayor of Jerusalem, Nir Barkat, to act.

Tamara Alrifai, the agency’s director of external relations, is based full-time in Amman, and used to manage a team based at UNRWA’s West Bank headquarters in East Jerusalem who travelled back and forth from Jordan. Since the October laws passed, none of the 30 or so international staff who used to work at the compound have been able to renew their visas, the last of which expired in January. Since then, the agency’s work on the ground has been carried out solely by UNRWA’s Palestinian staffers, with Alrifai’s team coordinating virtually.

When Israel’s ban came into force at the end of January, King celebrated. Outside the gates of the now-shuttered East Jerusalem site, he popped a bottle of champagne on camera.

As the tour begins, the 51-year-old King, who frequently pauses, eyes closed, to concentrate and think a thing through, tells us that the “terror, Nazi organisation”, as he refers to UNRWA, is “poisoning” the minds of children in East Jerusalem against the Jewish state. “For years, the Israel Land Fund fought against UNRWA... nobody wanted to listen,” he says of the NGO. It was only after 7th October that “people started listening”.

In her six years at UNRWA, Alrifai has repeatedly heard three claims against the agency, she tells me over video from her home office. First, that it teaches hate in its schools (there has been some evidence of antisemitic and anti-Israel content at UNRWA schools; Alrifai says that they teach the local curriculum, which in East Jerusalem’s case is the Palestinian one, and that “UNRWA reviews all pages in line with UN standards and does not teach sections that are not in line with UN values”); second, that UNRWA employs Hamas members (she notes that the independent review did not find that the agency had been systematically infiltrated by Hamas); and, third, that it preserves the refugee status of Palestinians.

It is this third charge which best explains why parts of the Israeli right see UNRWA as such a threat. The fact, in their eyes, that UNRWA perpetuates the idea of the right of return of Palestinian refugees is nothing less than an existential threat to the Israeli state.

Given these charges, the ILF is not the only right-wing group claiming credit for Israel’s UNRWA ban. On 2nd February, an ultranationalist NGO called Im Tirtzu convened a meeting over video call “with many stakeholders” who had been part of the effort. Arieh King, dialling in while driving in Jerusalem, was lavished with praise for his effort in getting the legislation through the Knesset.

“There’s no question he’s played a very big role… in spreading disinformation and accusations and mobilisation against the agency,” UNRWA’s communications director, Juliette Touma, tells me.

For months before the Knesset passed its ban, King shared incitement against UNRWA on social media: on 30th April 2024, for instance, he branded the organisation a “Nazi-Muslim enemy”. He repeatedly tagged Israeli politicians—from Knesset speaker Amir Ohana to Netanyahu and members of the Foreign Affairs and Defence Committee—to lobby them on the legislation.

Offline, he promoted and led protests outside UNRWA’s compound in East Jerusalem. One video from 14th February 2024 shows him at the centre of a small crowd waving Israeli flags and carrying banners reading “Get the enemy out of Jerusalem” and “Jerusalem won’t be Gaza”.

“The same UNRWA people that were there [in Gaza] are now here,” King told his fellow protesters. “The enemy is here. It’s not that there is an UNRWA in Gaza and it’s a different UNRWA here in Jerusalem. No, no. It’s the same UNRWA.”

The “headquarters of the terrorist UNRWA organisation” (as the ILF flyer described it) is the second stop on our Jerusalem tour. For what feel like several long minutes, our coach drives by the metal perimeter fence, past rows of low white buildings inside. It looks closed. Quiet. Opposite is Maalot Dafna, a Jewish settlement established after the Six-Day War, when Israel occupied Jerusalem and the West Bank. It has green trees and pale golden-yellow buildings—the colour you see all over Jerusalem; “Jerusalem the Golden”, the song goes.

Over months, amid the steady drip of incitement, demonstrations against UNRWA grew increasingly hostile. “They accused us of holding hostages in that facility,” Touma says.

On 7th May 2024, Philippe Lazzarini, the commissioner general of UNRWA, shared a video on X of an angry crowd outside the gates of the compound. Protesters can be heard shouting to get rocks. “This protest called by an elected member of the Jerusalem municipality is nothing less than harassment, intimidation, vandalism & damage to UN property” Lazzarini wrote.

Two days later, Lazzarini shared another video, this time of an apparent arson attack against the compound. Singing can be heard, “may the UN burn down”. This is a particularly combustible location; petrol and diesel stations for the UN fleet of vehicles are located on the premises. Lazzarini announced he would temporarily close the compound “until proper security is restored”.

King reposted the video, with the caption: “First is @UNRWA HQ at Maalot Dafna. Second will be the enemy HQ at French hill. And third will be the Natzi [sic] organization HQ at Qalandia. No place for enemy in our holy city.” In a news report that day, he is cited as saying: “What a privilege to be to blame for the closure of the headquarters of the Nazi antisemitic enemy.”

Five days later, on 14th May, Lazzarini posted more footage from Israeli media. The grainy video shows fire raging behind the UNRWA HQ’s perimeter fence. In September, King was questioned by police on suspicion of inciting violence and terror for attacking UNRWA on social media, alongside other posts, including one showing activists vandalising a truck with humanitarian aid for Gaza, captioned “I salute you”. King, who was released without charge, at the time defended his posts as “legitimate”.

King doesn’t like the phrase East Jerusalem. It implies a division of the city, which he believes is the eternal capital of the Jews

The Maalot Dafna compound has been virtually empty since the end of January, when the Israeli ban came into force. At the front of the coach, microphone in hand, King tells us there are plans for the now-empty lot and both Jerusalem’s mayor, Moshe Lion, and Israel’s defence minister support them. King thinks it would be fitting to move a nearby Israel Defense Forces (IDF) conscription centre there, and to build a museum dedicated to soldiers and civilians killed on 7th October as well as a new neighbourhood (“to bring more Jews here”).

Only eight days earlier, the municipality had issued 30-day closure orders to six UNRWA schools that teach about 800 pupils between them in East Jerusalem. On Facebook, King shared the paperwork. “This is an act that will go down in Jerusalem’s history books”, he wrote.

King doesn’t like the phrase East Jerusalem. It implies a division of the city, which he believes is the eternal capital of the Jews. “By the way,” he says, as the coach drives round the compound, “I’m going to the States in a month, and I am going to meet in Washington a few politicians in order to pass a law in the United States that would forbid them from using the phrase of East Jerusalem. There is one Jerusalem. Only.”

“Amen,” calls out one of the men on the tour. The coach bursts into cheers and applause.

During Donald Trump’s first administration, in a change from decades of foreign policy, the US became an international outlier by recognising Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. The US embassy was moved from Tel Aviv.

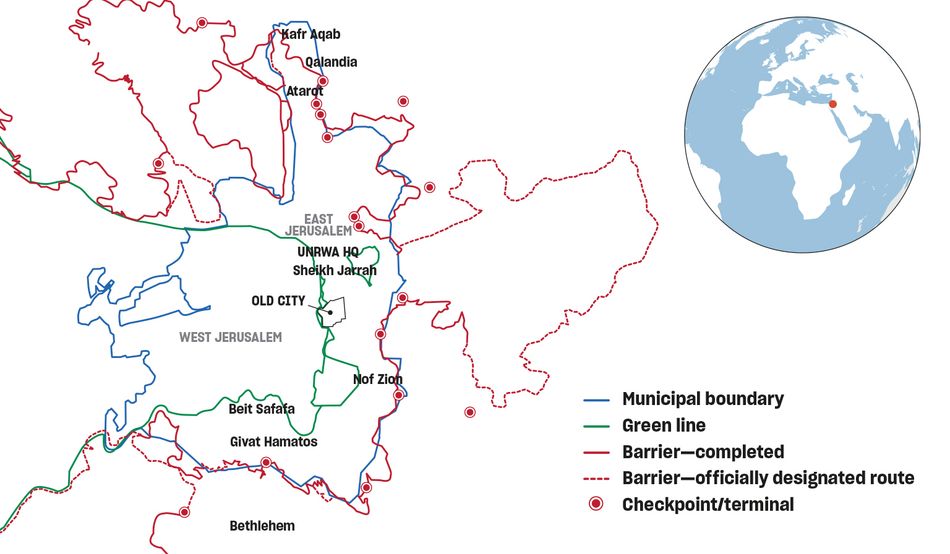

Israel’s main airport is in Tel Aviv, but Jerusalem once had one, too. Built in the 1920s during the British Mandate, the site in north Jerusalem has been abandoned since the Second Intifada began in 2000. On a dirt road the group gathers around King. On one side is the Qalandia checkpoint, to the other is the long-empty control tower of the former airport. Ahead of us is a concrete section of the security or separation barrier which Israel started building during the Second Intifada after a series of deadly Palestinian attacks against Israelis. It now snakes around Jerusalem, dividing the city from the West Bank and essentially annexing territory to Israel, including various settlements and Palestinian neighbourhoods.

More than 350,000 Palestinians live in East Jerusalem. After Israel occupied this area in 1967, Palestinians there were given permanent residency status, which they can lose if they leave for extended periods. The underinvestment in—and neglect—of Jerusalem’s Palestinian neighbourhoods is well documented and, human rights organisations allege, by design. It is harder to build in these areas, harder to get your rubbish collected. Home demolitions are at a record high. The municipality allocates less funding to them. East Jerusalem Palestinians can vote in local elections, but not national ones.

King climbs to the top of a mound of earth and rocks and invites us to follow. The area we are looking over is emblematic of the complex, often absurd bureaucracy of the occupation. Considered by Israel to be part of Jerusalem, the Palestinian Kafr Aqab neighbourhood was isolated by the separation barrier after the Intifada. As a result, its Palestinian residents are in limbo. But for King, the story at this stop on the tour is of formerly Jewish land no longer being home to Jews.

On the site of the former airport once stood a Jewish town, called Atarot. It was there until the 1948 war, when, amid the fighting, the Haganah, a Zionist paramilitary group, ordered the 200 or so residents to evacuate. For years, there has been talk of a major Jewish settlement here. “This area will be built,” King tells the tour, “it’s just a matter of time.” The only thing stopping it is politics. But King is patient.

“We are in the middle of the geulah, it is happening. It will take one year, another year, another day, another two years, five, it will happen. Jerusalem is older and stronger than all of us together.”

There is an UNRWA property in Kafr Aqab—it’s the site of a school—which King says was built on Jewish National Fund land. He wants the Israeli government and Jerusalem municipality officials to be based there and to “bring back the law” to the area, which he describes as lawless, practically a dump.

King refers to the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 CE. “It’s written,” he says, that every generation that does not rebuild the temple, it’s as if “the temple was demolished” anew. “The only question I ask myself… at least once a day, besides when I pray, is what I did today for making [the redemption] in our days… building Atarot, it’s part of it, and throwing out UNRWA, it’s part of it.”

He is part of it, too, he says. “I am a son of new immigrants. My parents are British… you hear my accent.” King is making fun of the English he speaks with a thick, Hebrew inflection. The mostly Anglophone crowd laughs. He says his grandfather was a councillor in London.

Breaking his flow, the deputy mayor turns to the youngest of the three boys on the tour, who might be six or seven years old. “Where were you born?” The US. “He was born in the United States and he’s here. I think it’s part of the redemption... Jews returning back to Zion, this is part of the redemption.”

The young child is flattered by the attention, this meaning suddenly bestowed on him. He glows with pride and embarrassment.

King was raised in Alumim, a religious kibbutz in the Negev desert. It was one of the places attacked by Hamas on 7th October (more than 60 people were killed in or around the kibbutz, including 22 students and foreign workers from Thailand and Nepal). Like most Israelis he served in the IDF (he is still a reservist) and later studied political science, Islam and the Middle East at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, learning Arabic. A father of six, he is a founder of Maale Zeitim, an East Jerusalem settlement. He tells us he joined the city government because he could better pursue his vision from within the system.

One of King’s fellow councillors at the municipality was Pepe Alalu. Now in his eighties, the Peruvian immigrant to Israel is a well-known Jerusalem politician of the left, recognisable by his long grey hair and beard. Alalu refused to go into coalition with King, and left his party, Meretz Jerusalem, when it went into coalition with King’s right-wing and religious list. He describes the deputy mayor as clever (“not like Ben-Gvir”), cunning and “even chamud [likeable]… he was constantly looking to build good relationships”. Aside from the years of coalition negotiations with King (who “offered me a deal”), for some time Alalu’s office was across the corridor from King’s.

“He was a person who worked,” he tells me. He was always busy, always meeting people. Elad, a settler organisation focused on holy sites, “was at home” in King’s office. Alalu says he knew that King was connected to the threats and violence by settlers in Sheikh Jarrah against local Palestinian residents. “The people of Sheikh Jarrah were scared of him,” he tells me.

Mahmoud Saou, 57, a Sheikh Jarrah resident under threat of eviction, recalls a time in 2006 when King made him an offer to leave the house he grew up in. King came “kindly”, he says, drank coffee and offered large sums of money. “He told me, ‘Mahmoud, listen, I don’t want many years in the court. This is my house, and in the end, I will take it.’” After Saou refused, he says King continued to pressure him via various intermediaries. “Every two weeks, he sent me somebody.” But he doesn’t get his hands dirty, Saou says: “Arieh King does a lot of things, but Arieh King uses his mind more.”

On the Jerusalem tour, King took us to a house where settlers live in Sheikh Jarrah. He had planned to take us inside, but whoever lives there didn’t pick up the phone. The house has a high metal fence around it, CCTV, a lemon tree. Saou and another activist tell me the house is used as a base from which to attack Palestinian cars or homes in the neighbourhood. “When we try to stop them, we are arrested,” says Saou. (One of Saou’s sons is currently serving a five-year prison sentence.) In response, King says he is “unaware of such claims”. On the tour he tells us it is the Palestinian residents who attack the cars and homes of Jews living in Sheikh Jarrah.

In February 2022, the politician Ben-Gvir set up an office in the neighbourhood in support of Jewish settlers. He is a disciple of Rabbi Meir Kahane—the founding father of a violent, fundamentalist and racist politics—and through his Jewish Power party he has managed to bring this extremist ideology to the heart of Israel’s government. In the 2013 Knesset elections, King was number four on the list of Ben-Gvir’s party. He didn’t make it into parliament, but he did win a seat on Jerusalem’s municipal council in the local elections that year. In 2014, King handed out flyers in Arabic to Muslim Palestinian residents of the city calling on them to leave the country: “In the Torah it is also written that the land of Israel, this small land, belongs to the Jewish people alone and it is forbidden for others to live here in a permanent manner.”

Despite such activity, Alalu doesn’t think King is a Kahanist like Ben-Gvir. Neither does Nir Hasson, the veteran Jerusalem correspondent of Israel’s Haaretz newspaper, who has known King for 20 years. He explains that the deputy mayor has been pulled in Ben-Gvir’s direction because that’s where the power is. “He doesn’t walk in the streets and hit people. He is old school,” says Hasson. King has also grown more “statesmanlike” since becoming deputy mayor, he adds, and likes to talk about having “good ties” with Palestinians in the city.

Another Jerusalem insider says King “likes starting up trouble”, that he’s “a known unknown”. In 2008, when George W Bush visited the city, King said he would establish a new settlement in Gilo, near the border between Bethlehem and Jerusalem. The mooted settlement never came to pass. Besides, “one housing minister does more harm than King does in a day,” Hasson adds. “His mouth is bigger than his hand… He talks a lot.”

King is certainly ideological, though. He opposed the security barrier between Jerusalem and the West Bank because any demarcation in the land of Greater Israel, any division of the eternal capital of the Jews, is no good. The 7th October attacks prove his point, he tells us. The Gaza border fence didn’t stop Hamas. In the Gilo area, at Givat Hamatos, the site of a massive new settlement under construction next to the small Palestinian neighbourhood of Beit Safafa, the deputy mayor kneels down and picks up earth so it runs through his fingers. At this site “you will feel the dust, the holy dust of Jerusalem,” he had told us on the coach.

On the tour, King explains how the ILF and other settler groups are focused on different parts of Jerusalem. Over years, Israeli authorities have been developing rings of settlements that encircle East Jerusalem, cutting the territory off from the West Bank (as Givat Hamatos does to Beit Safafa).

For years King has also called on people to protest against Christian events in Jerusalem. The Jerusalem insider described King as “viscerally anti-goy [non-Jew]” and “anti-Christian”. In response to this article, King denied being anti-Christian, saying: “I am against any missionaries that are trying to make Jews become Christians.” In May 2023, not long after fellow extremist right-wingers Bezalel Smotrich, now finance minister, and Ben-Gvir formed a government with Netanyahu, King took part when dozens of young religious Jewish men demonstrated against an Evangelical event in the Old City. “Missionaries go home,” the protesters shouted at visiting Christians. The Israeli news site Ynet reported on a trend of Jews spitting at Christians and churches in the Old City.

Since 7th October and the start of the Gaza war, King has openly called on social media for violence against Palestinians in Gaza and “expulsion” of Palestinians. He referenced the Torah portion Lech-Lecha in a post urging the possibly violent “transfer” of Palestinians out of Israel. In numerous other posts, he calls out the Israeli government and army for not having destroyed the cities of Gaza.

Over the five or so hours that I listened to King in Jerusalem, it seemed clear that in his eyes, and in those of the tour group, Zion would be better with fewer Palestinians in it. One could also infer that King thinks Muslims are to blame for conflict in the Middle East. I lost count of the number of times a member of the tour asked him, in one way or another, “How do we get rid of them?” When King told a story about Jews selling land to Palestinians, or allowing them to stay on Jewish-owned land, the group erupted in cries of “No!” and “Shame!”

Under the hot sun at Atarot, King tells us he thinks all of East Jerusalem’s Palestinian residents should be given Israeli citizenship. Not even leftists, who he says “are so racist”, want this. So why does he want it? Because Palestinians pose no demographic threat (“I’m not afraid of another two Knesset members, believe me there are some Arabs that are better than Jews that are in the Knesset”). Being “Zionist prisoners”, as he described them, many will likely leave, and, in any case, the “Christian Arab [sic] will integrate like the Christian Arab [sic] integrated in the Galilee and in Yafo.”

The deputy mayor represents the shift of Israeli politics to the right, and his brand of messianic, religious extremism to the mainstream

At that same stop, when a member of the group asks “why not pay them to leave to Indonesia,” King does also say he is “working on a much better option” of relocating Palestinians to Forest City, an abandoned development in Malaysia. “If you take all of Gaza, give them an island in a Muslim country called Malaysia,” he says, “we will not see them.” (On 8th May, he tagged Donald Trump in a Facebook post about Forest City as a place to send Palestinians from Gaza to live.)

King represents not just the shift of Israeli politics to the right but also of his brand of messianic, religious extremism to the mainstream. It is from these parts of the Israeli political spectrum that the calls to resettle Gaza with Jews, audible since the Gaza war began, have emanated. It is from these quarters, too, that some have described the war as an opportunity.

It is this ascent to power of the fringes that so empowers the likes of King. The deputy mayor has little time for Netanyahu, who is not right wing enough. He refers to Israel’s government as “right wing”—with air quotes.

“If you’d have asked me five years ago, I’d say [King] is a dangerous man who makes Jerusalem unstable and brings violence to the city,” says Hasson, “but when I look now, I say ‘this is what I was scared of?’” The situation in Israel is so terrible now, he says, that King is not even a threat anymore.

But King joining the coalition five years ago, being made a deputy mayor, was a sign of things to come. “Jerusalem heralds developments that are happening in Israel,” says Hasson. King’s appointment was an early warning signal of the coalition that Netanyahu would form in December 2022—the most extreme, right wing and religious government in Israel’s history.

“He was on the lunatic fringe and now he is in the deputy mayor’s office. This shows that something has shifted,” says the Jerusalem insider. Sahar Vardi, an Israeli activist for Palestinian rights in East Jerusalem, tells me that King “represents an entitlement of the settler movement now”. The system works for him.

At Givat Hamatos, the deputy mayor is busy telling us a convoluted story about how the land here came to be bought and developed for Jewish settlement, when a surprise visitor gets out of a taxi. Kevin Bermeister, a South African-born Australian tech entrepreneur with various real estate investments and projects in Jerusalem, was one of the characters in King’s convoluted story. According to King’s telling, Bermeister’s money helped secure the first new Jewish settlement in East Jerusalem in 20 years.

The Givat Hamatos plans were originally approved in 2014, but progress has been slow. In 2020, when Israel opened the bidding to build more than 1,000 residential units here, the UK condemned the move. At the time, King wrote to Boris Johnson: “As a British citizen as well as emanating from a family with close ties to the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom, I was both surprised and dismayed to read that Britain has joined several European countries in ‘reiterating grave concerns’ regarding construction in the Jerusalem area.” Now, Givat Hamatos is a vast building site, snaking up the hill, dotted with cranes. The Old City is visible in the distance.

Bermeister says that for two decades he has been travelling to Israel six or seven times a year, and that he and King have “built a very long-standing relationship on lots of different properties”. This pursuit is a “complex land conveyancing exercise”, which requires reference to British and Ottoman land records; plus, you need to know Hebrew. “So I had to find an Englishman,” Bermeister says.

In April, the Met police were given a dossier of evidence accusing 10 Britons who served in the Israeli army of committing war crimes in Gaza. Under the Geneva Conventions Act (1957) and the International Criminal Court Act (2001), British nationals can be investigated and prosecuted in the UK for “core international crimes” committed elsewhere. Legal experts I spoke to say that, though it is technically possible for Israelis with British citizenship to be prosecuted here if they have committed such crimes, it is highly unlikely. Even if the high bar of prima facie evidence were reached, the attorney general would probably not consent to any prosecution, such consent being specifically required under the 2001 Act. And even if such consent were given, getting the accused to the UK would be a challenge in itself. Whether settlement activity, incitement against UNRWA or calls for violence or “transfer” on social media would count as “core international crimes” is clearly another matter. In May, the Wall Street Journal reported that the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor, Karim Khan, had been preparing arrest warrants for Smotrich and Ben-Gvir over their roles in promoting West Bank settlements. (The status of those warrants is unclear; Khan went on leave from the ICC following sexual assault allegations against him.)

Bermeister re-joins us at our last stop: Nof Zion, an East Jerusalem settlement where he is financing an expansion of the neighbourhood. I count nine new apartment blocks, Jerusalem gold-brick with touches of black metal, curving around the hill. The first Jewish family has just moved into one of these flats, King says. It’s going to be 600 units, all told, making it the biggest private settlement project in East Jerusalem, he tells us. The blocks look out onto a panoramic view of the city. In the distance, to our left, is the deep copper-gold of the Dome of the Rock. To our right is the separation barrier.

When we get back on to the coach, an elderly American woman who lives in the West Bank settlement of Beit El asks me if it’s true that Islamists are taking over London, and whether it’s a problem having a Muslim mayor. The American man sitting in the row of seats behind me asks if I am interested in hilltop tours, visits to illegal settlement outposts in the West Bank. King gives out his phone number. We can call him, any time. “We must find a way to support this,” the woman from Beit El says to her husband.

Meanwhile, the UNRWA headquarters remain empty. The law banning contact between Israel’s government and the UN agency, in force since 30th January, had already made it “impossible to coordinate movement (of staff and humanitarian convoys, for example)”, as Tamara Alrifai tells me in an email. With Israel no longer granting visas to international UNRWA staff, they could no longer “go in or through Israel to reach areas that we operate in”, such as the West Bank and Gaza. To this, King responds that: “There are other UN agencies providing humanitarian supplies as well as educational services.”

The week after the tour, on 22nd April, the UN relief coordination office would say that the humanitarian situation in the Strip was “probably the worst” it had been since the start of the war. This was, after all, the longest period that no aid or other supplies had entered Gaza since the war began in October 2023. But Israel’s UNRWA ban had gone into effect even before the blockade. The legislation had directly contributed to the hunger of Palestinians in Gaza. Such tremendous suffering. But King is working for the geulah. The redemption. It’s happening.