Up high on a screen attached to the front of the Rijksmuseum’s southern façade, Steve McQueen’s Occupied City plays for all and sundry. As a purely visual record, you’d be forgiven for thinking this was not much more than a study of the beautiful mundanity of urban life; perfect shots of Amsterdam’s sun-gilded streets and canals, many of them oddly vacant. Indeed, it makes perfect sense for McQueen to namecheck Vermeer, whose works he beelined towards on his first visit to this museum after making the Dutch capital his home in 1997; it was Vermeer, with his deep yet intricate studies of city life, that taught him about the “weight of images”.

Yet down in the museum’s auditorium, where the same pristine visuals are accompanied by audio narration, a very different story emerges. Here, we’re told, is the house where a man was arrested for having “carnal intercourse with Aryan persons”; here is the canal where a Jewish butcher, fleeing arrest, had leapt and died. His death was recorded as suicide.

As its title suggests, Occupied City is what McQueen describes as a “living archive” of some 2,000 addresses, alongside details of who lived where during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, originally compiled by his partner Bianca Stigter as the book Atlas of an Occupied City in 2019. A shorter version of the film was released in late 2023; that was four hours long. This definitive version, the director’s cut you might say, is 34. Officially touted as McQueen’s first “documentary”, in many respects Occupied City is of a piece with his feature films like Hunger, 12 Years a Slave and Blitz: a slantwise take on a well-worn period, a deep examination of lives brushed aside by history.

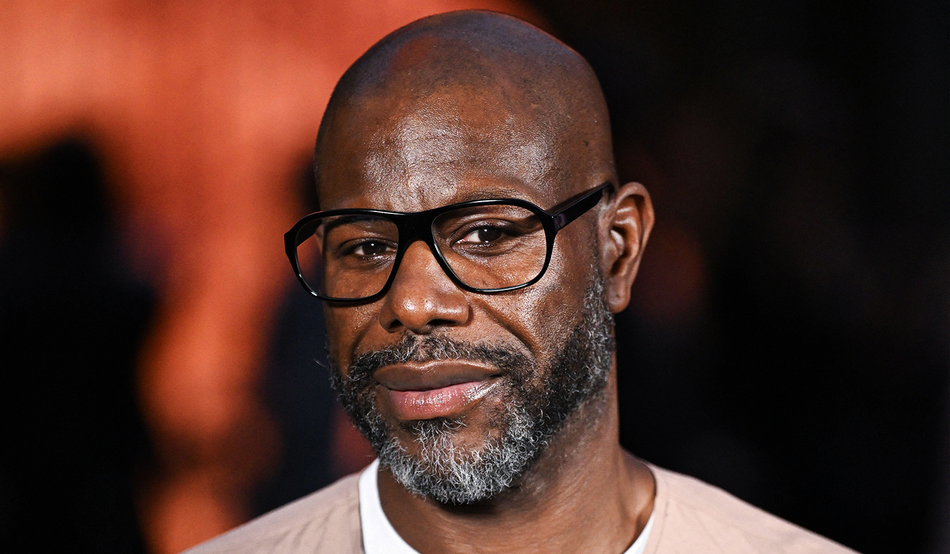

That morning McQueen and Stigter are sat outside the auditorium, taking questions one at a time from a queue of journalists; the atmosphere is not unlike the waiting room at the dentist. Regardless, when it gets to my turn McQueen is garrulous; his is the kind of voice that makes you stop and listen, every word carefully enunciated without ever being slow off the mark.

Unlike today’s media scrum, perhaps, McQueen tells me his film is not supposed to be an exercise in endurance. “You can look at it for half an hour or 20 minutes or for three hours. It’s what you take away from it. And, when you come back to it, what you add to it.” It’s for this reason he’s particularly pleased to have the film shown on the side of a building, allowing it to exist embedded in the fabric of everyday life; what the film might say to you can shift depending on what you see, and when.

There’s also a parallel to be drawn here with McQueen’s personal experience of Amsterdam, which—unlike the west London of his formative years—he describes as akin to “living with ghosts”. Down every street of this city, which celebrates its 750th anniversary this year, are thousands of life stories. No matter how distant or removed they might feel from our own, they have left their mark.

Anniversaries, the Second World War, Vermeer—for all this talk of the past, McQueen is really keen to emphasise the role that artists can or should be playing today. “We have to think of the now, think of the present,” he urges. “As an artist, I’ve never felt more useful than now.” A hint of what he might mean by this can be seen in Occupied City itself. One of the addresses highlighted is that of Max Beckmann, the German artist who fled to Amsterdam in 1937 after the Nazis classified his art as “degenerate”. Even when the Netherlands was subsequently occupied in 1940, Beckmann continued to make work in defiance of the regime.

“I don’t think people stop and start doing things differently,” McQueen says, when I ask him how he thinks contemporary artists should likewise respond to the world around them. “People look for things because of the situation they find themselves in. But to be in a situation where you’re working is enough.” The conclusion isn’t that making art is hard, because that’s always been the case; rather, McQueen says, it’s that by making art we create a space of possibility.

Later, as I’m leaving the Rijksmuseum, I catch a glimpse of McQueen and Stigter out on the street. They’re looking up at the building, at Occupied City. I think of the people who have left their mark here across centuries. Seeing the two of them watching the film with a dozen other passers-by, I get the feeling that McQueen and Stigter have added more than just their own.