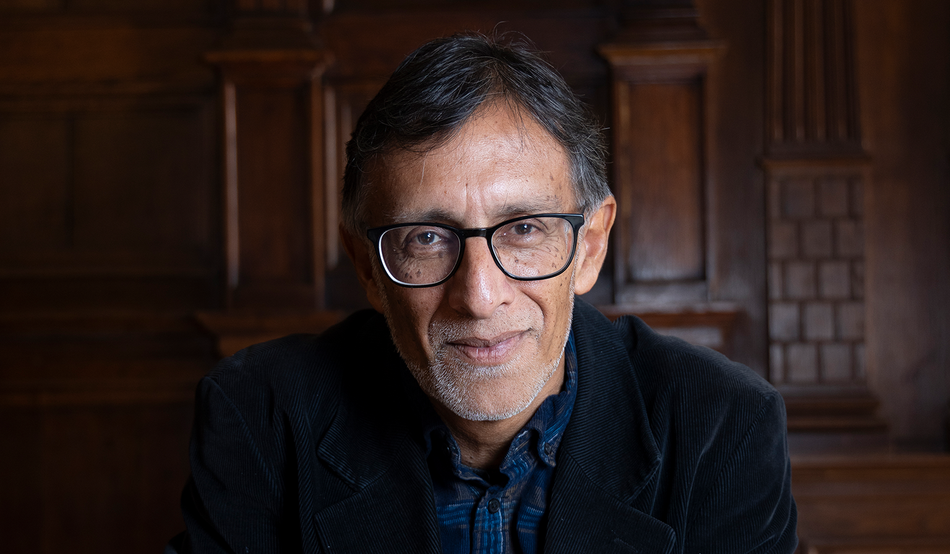

When I last spoke with the historian Sudhir Hazareesingh we were talking about Black Spartacus, his prizewinning biography of the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture.

Now, we’re meeting again in his dimly lit office at Balliol College, Oxford to discuss a “bigger story about slave revolt”, one that Hazareesingh says was “just seen out of the corner of my eye” while researching the life of former slave Louverture. The history he glimpsed several years ago has now become his new book Daring to be Free, a colossal account of slave resistance spanning four-and-a-half centuries, which argues that “resistance is not an exception” or “marginal”.

Hazareesingh speaks in a steady, deliberate manner. Undertaking the project “was a momentous decision”, he says, as his gaze drifts towards a window overlooking the college quad. The university has been his home for over 40 years, after Hazareesingh arrived in 1981 from Mauritius on a scholarship. “I found myself moved all along,” he says of writing Daring to be Free, “because I kept trying to think about how it must have felt for them.”

Equally, he admits that covering such a long period was “daunting”, especially given that much of what enslaved people thought and said to each other is “lost forever, simply because it wasn’t written down”. For him, this absence is “incredibly touching” and reinforces the urgency of his work.

Despite the challenge presented by the scarcity of primary sources, Hazareesingh was surprised that “nobody had written this book”. Sinking back into a battered sofa, he offers two reasons. He points out that “like most academic endeavours, there’s the question of specialisation”, which limits the potential for exchange between those focused on different genres of resistance, such as written as opposed to oral slave narratives.

“I think the other reason is to do with Marxism,” he says, before cracking a mischievous smile. Scholars who wrote in that tradition, such as CLR James, “tend to take things up to a certain point, but then encounter a conceptual problem because the events do not fit within tidy Marxist schemes”. The revolutionaries “aren’t workers”.

Filling this vacant spot, Hazareesingh’s book engages in a campaign of recovery, dismissing the idea of “quiescent slaves who very slowly and gradually gain political awareness”. In doing so, he had to look critically at the abolitionists. Upon closer inspection, he found them to be “ambivalent about black power, to put it very bluntly”.

Instead, Hazareesingh, wants to reach out for “the voice of the enslaved themselves”. Their voices, he thinks, have been neglected by people who have written about resistance, “partly due to an underappreciation of the military training that a lot of these people had.”

What emerges is a story about dignity and honour—two words woven throughout the book. “Dignity and honour are paramount because they connect enslaved people to the idea that freedom is something they’re entitled to.” Both qualities, Hazareesingh says, show that “these people were resisting in ways that were very similar to other groups fighting imperialism or monarchical tyranny, and working for the idea of self-government.”

As he discusses the way slavery is remembered in the present day, Hazareesingh departs from the book’s largely phlegmatic tone. “In order to have a proper conversation, everybody has to be agreed on the basic facts,” he says.

“Having [written] ten chapters that allow the facts to speak for themselves, I wanted to weigh in on the role of all this information in the public conversation.” There is no doubt about the side on which Hazareesingh comes down. The conclusion positions the book as “a contribution to the case for reparations.”

When asked about contentious public memorialisation, like statues of slave owners, Hazareesingh says he is “completely against tearing things down”. Rather, he invites people to grasp the opportunity to tell a very different story, one which is “actually quite upbeat—about collective empowerment, democracy, and dignity.”