The hour-long coastal cycle ride from Margate to Ramsgate offers a vivid illustration of the paradox of England’s relationship with its seaside, one of both intense affection and careless neglect. With the North Sea on one side and the English Channel on the other, the promontory has an ancient history of intimacy with the continent. Writers, artists and filmmakers are drawn to the place as a barometer of the state of the nation, most recently Sam Mendes with his 2022 film Empire of Light. Set in the 1980s in the magnificent shabby grandeur of Margate’s art deco amusement park Dreamland, among the broken glass and seagulls, Mendes’s portrayal of the febrile mix of precarious mental health, racism and eccentricity on the coastal edge is instantly familiar. Margate may have become a national model for arts-led regeneration, but the resort is still dogged by the acute deprivation that has become a coastal pattern. Despite investment, three areas of the town are some of the poorest neighbourhoods in the UK.

The deindustrialisation of England’s seaside resorts—you could call it a salt fringe rather than a rust belt—has unfolded over the past four decades with only a fraction of the political engagement and public commitment needed for them to find a new future. Instead, austerity, the pandemic and now the cost-of-living crisis have exacerbated their plight. But rather than mobilising outrage, these resorts—with their tatty hotels and amusement arcades—appeal to an English appetite for bittersweet nostalgia and provoke fatalistic complacency.

Margate’s Turner Contemporary gallery has been heralded as a great success. By some measures, that’s true; visitor figures quickly ran way ahead of predictions after opening in 2011, as “Down from London” incomers (or DFLs, as they are known) moved in, bringing energy and investment. With them came decent coffee shops, good food, boutique hotels and a rejuvenation of the town’s charming period houses. But the steep rise in housing prices has crippled the supply of rental properties and concentrated the deprivation in small pockets. For the seaside towns that can gentrify—those with historic centres and proximity to wealthy cities, like Margate and elsewhere in Kent—it has proved something of a Faustian pact, bringing a degree of regeneration while deepening the inequality that was already there.

The pattern of coastal poverty is evident in every part of England, from Scarborough in North Yorkshire and Bridlington in East Yorkshire, as well as Skegness in Lincolnshire, to Clacton in Essex, Bognor Regis and Hastings in Sussex and Minehead in West Somerset. This coastal fringe of deprivation does not fit into the north-south divide that dominates the debate on regional inequality; nor is the policy agenda of “levelling up” of much help, given its focus on improving productivity and strengthening the economic centres of regional cities. Coastal towns like Skegness and Minehead have poor transport links, while their peripheral position halves economic opportunities and makes them the likely loser in any competition for investment. Successive governments have failed to recognise that seaside resorts represent a unique challenge to policymakers. An art gallery or a grant for hanging flower baskets on a high street do nothing to alleviate poverty or slow down the process by which many of these towns are becoming poorer relative to the rest of the country.

At the heart of their predicament is the conundrum that seaside towns serve as both trap and refuge. Together, these twin narratives interact in countless ways that undermine the struggle to reverse their long-term decline and the poverty that cripples them.

On a winter’s day in a wet Torquay, with the salty winds battering the harbour front, I chat with the manager of a fish and chip shop. Cheerful and efficient, she proudly tells me how she went to university as a mature student and got a degree in biology, but since then has struggled to find a better-paid job. She insists that she and her husband, a chef, have a great quality of life near to both their families and that their four sons love living by the seaside. It is enough to compensate for the lack of opportunities, she claims. And countless others in these towns might say the same: they love the places and strong communities into which they were born. Yet they can also resent that it has come at the cost of a better quality of life, and that they cannot afford to move to a wealthier area of the country.

There are two factors that sustain the seaside town as a “trap”. The first is low pay; median pay in almost all coastal towns (Brighton and Hove and Bournemouth being the exceptions) is lower than the counties in which they sit and across the country’s average as a whole. Scarborough had the lowest average pay in the country in 2019, and of the places with the lowest pay, Southend and Worthing were the only contenders outside of the north of England.

This low pay is driven by the fact that the local economies are dominated by hospitality and care work, sectors that have lower productivity. As coastal towns fall further behind, most local authorities are keen to diversify their economies—but they are running up the down escalator. Given the lack of quality jobs, graduates leave, discouraging further potential investors.

Poor employment prospects contribute to the second challenge that seaside towns have in common: some of the lowest rates of educational attainment in the country. Over 20 per cent of Scarborough’s population aged above 16 have no qualifications (academic, vocational or professional), higher than the national average. Twenty years ago, the biggest challenge in education policy was inner cities. Now it is coastal and isolated rural communities, where a culture of low aspiration has set in, which in turn reinforces the difficulty in recruiting good-quality teachers. Schools are not helped by a funding formula that still disproportionately benefits inner-city areas. In 2022, for example, Kent received £4,367 for each primary school pupil and £5,679 for every secondary school child, compared with £6,356 and £8,501 respectively in Hackney in east London.

Meanwhile school resources in many coastal areas are overstretched by a disproportionate number of looked-after children (those who have been taken into local authority care) who often need extra support. Blackpool has the highest proportion of looked-after children in England; many private children’s homes have opened in the town in the past few years, generating big profits for their owners but creating a concentration of vulnerable youngsters with special needs who might be hundreds of miles away from their hometowns.

Low pay and low aspiration translate into shorter lives and a higher burden of ill health. Levels of obesity, smoking and substance abuse are higher than the national average in coastal towns. Dig down into the street-by-street data and the differences in life expectancy are dramatic. As you head south from Morecambe along the promenade to the village of Heysham, residents’ lives lengthen. It’s a similar story on the North Somerset coast, where the few miles of muddy shore between Weston-super-Mare and Clevedon could add more than a decade of life.

Back in Margate, the cycle trip along the coast takes you past the acute deprivation of the Cliftonville area to the luxury housing estates of North Foreland just a few miles on, now the site of new gated property developments where a three-bed flat with floor-to-ceiling views of the sunrise over the North Sea will set you back £1.2m. North Foreland was in the top decile of the least deprived places in the UK in 2019. A little further on and you reach the quaint and expensive charms of Broadstairs, much loved by Charles Dickens. Along this stretch of coast, you find examples of every element that forms the pattern of the English seaside resort: those trapped in seaside towns they can’t afford to leave; the spillover of urban wealth in search of second or retirement homes and buy-to-lets; and the desperate, in search of refuge, with nowhere else to go.

This last category is where things become tragic. Seaside towns had already faced the challenge of the end of the mass annual fortnight holiday market. But their struggle has been compounded by the fallout of rising costs in wealthier neighbouring cities and regions; as property prices soar in Manchester, London and Bristol, those who can’t find affordable housing there take the train to the end of the line. These can be troubled people fleeing demons such as domestic violence, drug abuse or a prison record. Often they can only find a cheap bedsit to rent in places such as Jaywick in Essex (the poorest place in the UK for the best part of two decades), Blackpool, Hastings and Weston-super-Mare.

In Blackpool alone, of the 8,000 people who move into the town every year, 5,000 are on benefits and 44 per cent are single men; many end up in the former hotels that have been cheaply converted into Houses of Multiple Occupation (HMOs). It’s a Sisyphean task for local authorities to cope with the concentration of highly vulnerable people with complex needs for drug treatment, mental health support and rehabilitation.

Awareness alone fails to reverse the apathy and neglect

Meanwhile, HMOs have become a highly lucrative business model. Absentee landlords build up portfolios of old hotels converted into bedsits to create a steady rental income from housing benefit; Zoopla placed Blackpool as the second-most profitable buy-to-let destination in the country in 2020. The stamp duty holiday during the Covid pandemic triggered a mini buy-to-let property boom subsidised by the taxpayer, as millions in public revenue drained into the pockets of private absentee landlords. A further boost to landlord income has been the rise of “supported accommodation” for vulnerable tenants at increased rents, paid for by housing benefit, even though the availability of support workers who are expected to provide care with daily living can be variable or non-existent. Blackpool council’s efforts to lobby for increased powers to regulate the number and quality of HMOs appear to have been ignored in Westminster.

Despite residents’ short lives and diseases of despair, we still travel to the seaside in our millions; Blackpool’s visitor numbers of 13m a year (pre-Covid) exceed the British Museum or Buckingham Palace, while places like Clacton, Minehead and Morecambe are passionately loved. What’s required is a big shift in political focus of the kind that happened in the mid-1980s, when the deprivation of inner cities moved centre stage. The situation of seaside resorts has become increasingly clear during the past decade, but awareness alone fails to reverse the apathy and neglect.

In the first major national analysis of the issue, chief medical officer Chris Whitty focused his 2021 annual report on the nation’s health on coastal towns; he presented a map of England with the incidence of coronary disease plotted in red, a thick fringe of which clung to the coastline. Even after allowing for age and deprivation, Whitty pointed out a coastal excess of disease. A few streets in south Blackpool, he added, are now home to “the single most vulnerable population in the country in the most inappropriate accommodation”. He attributed the lack of action in part to the shortage of data at a sufficiently granular level, which had made the problem easy to ignore.

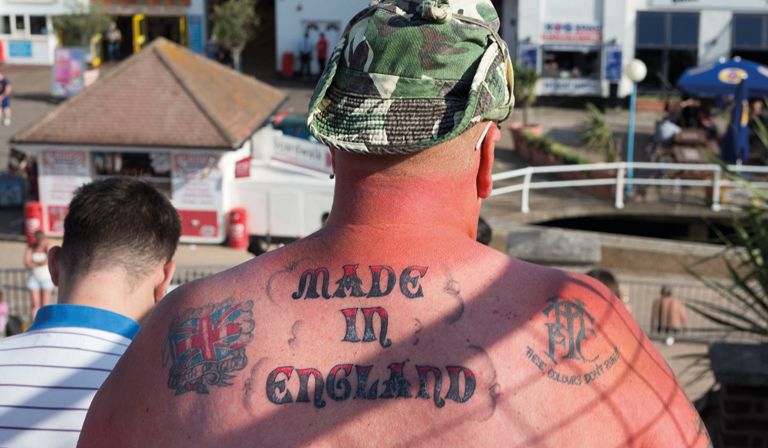

The combination of deprivation and affectionate nostalgia creates its own distinctive political expression. The seaside is seen as symbolic of a bigger national story. Blackpool has a wealth of film footage from its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s on YouTube, showing the promenade crowded with women in their Sunday best and men in three-piece suits. The accompanying comment thread is dominated by a generation of baby boomers trying to spot their parents and reminiscing about the magical days of childhood, seamlessly segueing into diatribes about how the country has gone to the dogs. The algorithms do the rest, as adverts for Nigel Farage’s financial services pop up with a narrative of national decline and how an elite is to blame. This is where the politics of nostalgia can become toxic. Attitudes can even veer into explicit racism: in February, the usual quiet of out-of-season Skegness was disturbed by a protest over the housing of asylum seekers in the resort.

The complacent assumption once was that political change was generated at the urban centre, not on the periphery—but Brexit put an end to that. Seaside towns—with the exception of Brighton and Hove—lodged some of the highest percentages of votes to leave the European Union in 2016. Douglas Carswell won a key byelection in 2014 in Clacton for Ukip, emboldening the Leave campaign. Matthew Parris’s column in the Times ahead of the vote was brutal: “Only in Asmara after Eritrea’s bloody war have I encountered a greater proportion of citizens on crutches or in wheelchairs… This is tracksuit-and-trainers Britain, tattoo-parlour Britain, all our yesterdays… I am not arguing that we should be careless of the needs of struggling people and places such as Clacton. But I am arguing—if I am honest—that we should be careless of their opinions.” That carelessness cost the country dear. The article appeared under the strapline that Clacton represented a “Britain that’s going nowhere. The future belongs to places with more ambition and drive.” Parris couldn’t have been more wrong: in 2016 the future was partly decided by places like Clacton, Great Yarmouth, Skegness and Blackpool.

The seaside periphery has a long history of racism—Mendes’s film includes a nasty reminder of National Front violence in the 1980s—and it is fed in part by historical anxieties of being on the frontline of possible invasion, a paradigm that Farage and the far right relentlessly exploit in the current crisis over small boats carrying illegal migrants into UK waters. The fear of invasion is a vivid memory on the Essex and Kent coasts, but many other seaside resorts such as Scarborough faced threats in both world wars. The history of the Second World War is kept fresh with copious memorials, ruins of fortifications and events, such as Clacton’s popular annual air show.

But this politics of the periphery has other, more progressive expressions; being on the edge can encourage a resourcefulness and self-reliance. This can be seen in the story of the town of Watchet in West Somerset, which offers one of the most hopeful examples of reinvention. The town lost its last major employer, a paper mill, in 2015—and given the hour-long public transport journey to Taunton and the M5, it was hard to see a future. Seven women set up the community enterprise Onion Collective to turn around decades of decline and the lowest rate of social mobility in the country. After years of organising cultural events and fundraising, Watchet’s £7m East Quay arts centre opened in 2021. Exhibitions, workshops, visitor accommodation, a café and events have brought new visitors to the town. East Quay is an inspiring example of what a determined group can achieve, one it’s not hard to imagine being reproduced elsewhere.

Jess Prendergast, a member of the Onion Collective, advocates the concept of “attachment economics”, which sees commitment to a place as a powerful mobilising force to rally the community. She argues that on the periphery: “There is an independence, and a deep attachment to people and the place. On many national measures West Somerset is at the bottom, but in studies of happiness and wellbeing we ran high. We may have no money and sometimes things are shit, but we have the things needed for wellbeing.” She says there are 150 local community groups in the town of 4,000 people. “The place is built on music and theatre. We can’t go out to the cinema or theatre so we do it ourselves. Who determines what the good life is? We shouldn’t be seen as left-behind. The levelling up agenda implicitly tells people: you must become like us. It’s condescending.”

East Quay is one idea of how to reinvent a seaside town. Eden Project Morecambe is another—the proposal to build a sister site to the Cornwall eco-attraction received a £50m grant from the Levelling Up Fund in January, to pay for a spectacular centre on the seafront. Both are exciting and inspiring, but they can’t—and shouldn’t—obscure the shocking national neglect of a pattern of deprivation and despair. What’s needed is a well-funded, long-term national vision of better public transport and digital connectivity to ensure that prosperity in this small island reaches the edge.

Corrections: the original text of this article referred to Cliveden in North Somerset. The correct name of the town is Clevedon, whose residents could have life expectancy more than ten years longer than that of poorer residents in Weston-super-Mare. The article also referred to Bridlington as being in North, not East, Yorkshire. This error has been amended.

The original text also described the proportion of Scarborough’s population without qualifications as “over 30 per cent”. The true figure is 20.6 per cent and the text has been amended to reflect this.