Ten years ago, one of the most notable international agreements was signed in an unprepossessing conference centre, in an unremarkable suburb northeast of Paris.

The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference—also known as the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21)—saw negotiators representing 195 nations gather in Le Bourget. Ultimately, almost all agreed to targets that would limit temperature rises to “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and to pursue other efforts to limit rises to below 1.5°C. The agreement also committed developed nations to provide poorer nations $100bn a year by 2020 to help them cut emissions and adapt to the effects of climate change.

The Paris agreement, adopted on 12th December 2015 and taking effect the following year, was imperfect. The language was looser than many wished for; its implementation relied on nations setting their own interim emission-reduction targets. In many ways the ensuing decade has not been kind to its legacy. And yet it remains an impressive, unprecedented piece of climate change diplomacy. The accord exceeded both the Kyoto protocol in its application to all nations—rich and poor, developed and developing—and the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, which set the parameters for future commitments but did not impose targets.

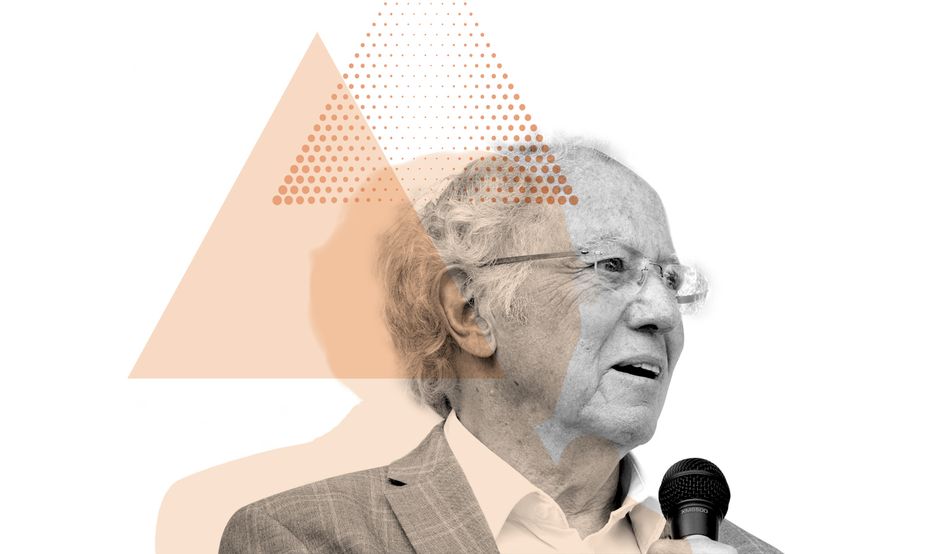

One British official who played a key role in its creation is David King. The chemist and academic—knighted for his public service in 2003—was the UK’s permanent special representative for climate change, working closely with foreign secretary William Hague and prime minister David Cameron. He’d held the same role when David Miliband was foreign secretary and Tony Blair was prime minister, and it was Blair who in 2000 brought him in as the government’s chief scientific adviser.

I visited 96 countries in two years. I was burning up a lot of carbon

King, now 86 and still active as emeritus professor of chemistry at Cambridge University, recalls that as special representative he required two things above all else—time and money. He knew he had to start negotiating in the months and years prior to COP21. The alternative was to wait and deal with around 20 officials per country at the conference itself. Dealing with thousands of negotiators in a few short weeks was a recipe for failure. “What we had to do was negotiate bilaterally,” King, sporting a white t-shirt and framed by an extensive library of books, explains when we speak over a video call.

To make that possible, climate attachés were assigned to UK embassies around the world. Their presence facilitated one-to-one discussions and signalled the importance the UK ascribed to climate diplomacy. “I visited 96 countries in two years,” recalls King. “I was burning up a lot of carbon.”

Fortunately, money also proved forthcoming. The exact amount was never publicly disclosed, says King, for fear of backlash from a climate-sceptical press. “The government was worried that The Sun, The Daily Telegraph etcetera would run a campaign and that would be the end of the budget.”

During those pre-Paris negotiations, two issues bubbled to the surface. The first was how to agree a suitable temperature limit. The more exacting 1.5°C figure went against the international consensus but when King attended a meeting in Papua New Guinea of island nations threatened with rising sea levels, he came away convinced by the new target. He called Number 10 and persuaded the prime minister to endorse a change of tack.

The second challenge concerned how to bring the United States into the agreement. For those, including King, seeking a deal at COP21 it soon became apparent that they couldn’t bake “top down” demands into the language of the accord. Why? Because Barack Obama, president at the time, lacked Congressional support and without the world’s largest economy as a signatory, the agreement would lack heft. The solution was to introduce nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Put simply, this meant each country would set its own targets. This was not an ideal fix but an example of pragmatism eclipsing perfection. King describes NDCs as “necessarily weak”.

Despite the US’s initial commitment to the Paris agreement, King is scathing about Washington’s role over recent decades, reserving equal scorn for the efforts of successive administrations. With the exception of Obama’s second term, he insists that the US has absented itself from climate change leadership. “The US has been a very negative force,” he says. “Imagine if, since 1992, it had decided to take a leadership role on this. Wouldn’t we have had [greater] agreement by now? I’m sure we would.”

Imagine if the US had decided to take a leadership role on climate change

Donald Trump is not such an outlier, then. Yes, he has twice withdrawn his country from the Paris agreement, but the current US president reflects a wider American climate scepticism, says King. It is a scepticism that is aided and abetted by “senators and congressman with money in their pockets from the fossil fuel industry”. Trump’s “bare-fisted, undiplomatic approach simply clarifies the US position.”

Such is his distrust, King would prefer the US not to be present at future negotiations. These include COP30, hosted in Brazil from early November. “My fear is that they are going to turn up,” he says. Why fear? Because, he believes the US would overwhelm the conference with scores of negotiating lobbyists “going around explaining to countries that there is no need to take [climate change] seriously”.

Clearly some things have changed in the last decade. Ten years ago, an eager Obama was an essential signatory at Paris. Today, King envisages a group of “willing nations” that excludes an obstructive US. He wants the group “to come together, whether formally or informally, at COP in Brazil and say, ‘We understand the nature of the risk and this is what we together are planning to do’.” King cites Mission Innovation, a global initiative designed to catalyse investment in research and development, as an example of what can be done together. Originally launched at the Paris conference a decade ago, Mission Innovation represents 23 countries plus the European Commission on behalf of the European Union.

The group of willing nations may not feature the US, but it does include China. King is impressed by Beijing’s progress. He accepts that the country continues to invest in new coal fire power stations but maintains these are in place in order to phase out older, less efficient power stations, and ultimately phase out fossil fuels altogether. He points to China’s investment in clean energy and to research by the Climate Crisis Advisory Group—a collection of interdisciplinary climate experts of which King is founder and chair—which indicates that, overall, Chinese coal emissions “appear to have peaked around 2013–2014 and stayed relatively flat since then”. (Tracking data from the United Nations suggests a 1.23 per cent increase in overall greenhouse emissions between 2013 and 2018). “China is a country that fully recognises the challenges of climate change,” he says.

Willingness in a one-party state is a little different to willingness in a democracy like the UK. The latter requires that the public consents to the direction of travel and the effort required to get there. Take net zero, for example. That’s the mission—inferred by the targets set in the Paris agreement and passed into law by the British government in 2019—to balance greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere by human activity with active removal of those emissions by 2050. Despite continued support among the public, the political consensus is fracturing. Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch used a speech in March to pronounce the mid-century target “impossible”. (See interview with Andrew Bowie, page 10). Perhaps a more surprising intervention came a month later from King’s former boss Tony Blair. Writing a foreword for a paper published by his institute, titled “The Climate Paradox: Why We Need to Reset Action on Climate Change”, Blair argued that “though most people will accept that climate change is a reality caused by human activity, they’re turning away from the politics of the issue because they believe the proposed solutions are not founded on good policy.”

Trump’s bare-fisted approach simply clarifies the US position

It turns out that King is a doubter, too. “I’m not a great fan of the idea of net zero,” he says, admitting that he was surprised that Theresa May chose to introduce it into law as one of her last acts as prime minister. Net zero, King says, is too vague a concept and it encourages focus on emissions capture at the expense of absolute reduction. “It would be much better for countries to be aiming for 90 per cent reduced emissions by 2050.” To that end, he applauds Keir Starmer’s commitment at COP29 last year to a target of an 81 per cent emissions reduction by 2035.

Rather than the orthodoxy of net zero, the Climate Crisis Advisory Group recommends adhering to four pillars (or, more colloquially, “the four Rs”). These are: reduce emissions, remove greenhouse gases, repair the planet’s climate systems and add resilience to deal with climate impacts and threats.

At COP30 discussion will centre on adaptation, meaning policies that address the impacts of climate change. Isn’t there a danger that by focusing on adaptation, it excuses policymakers from concentrating on the more urgent matter of mitigation? King says this is a false dichotomy. “You could say the same thing about ‘repair’ and ‘remove’,” he points out, referencing the pillars above. “We need all four Rs. If we simply were to reduce emissions—let’s suppose a magic wand allowed us to reduce emissions to zero tomorrow—Greenland ice will continue melting.”

I’m not a great fan of net zero

Finally, the conversation returns to Paris. How does King assess progress a decade on? He offers a mixed review. On the positive side of the ledger—and reflecting the view of UN secretary general António Guterres who declared in July that fossil fuels had “run out of road”—King welcomes the market’s embrace of clean energy sources. “Renewables are now the cheapest way to create electricity in most parts of the world,” he says. “It means that market forces are there to drive renewables onto the grid.”

On the other hand, he describes overall progress as “disappointing”. Figures vary—the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service recorded a 1.7°C temperature rise last year while the World Meteorological Organization measured mean temperature rises of between 1.4°C and 1.6°C. Either way, the average is approaching, or above, the 1.5°C aspiration King fought hard to include in the Paris agreement. He points to the “feedback effects” of this kind of temperature rise, such as ice melt, that are “dramatically changing” what had previously been forecast. He points to sea ice levels in 2023—the sixth lowest on record—as an example. “It’s not good news,” he says, with some understatement. “We need much better action.”