What hope is there for the future? On climate, you’d be forgiven for feeling bleak. Global greenhouse gas emissions are still rising, the impacts of past emissions are increasingly evident, and right-wing populists rage against net zero and call for the extraction of yet more oil and gas—while simultaneously winning over voters.

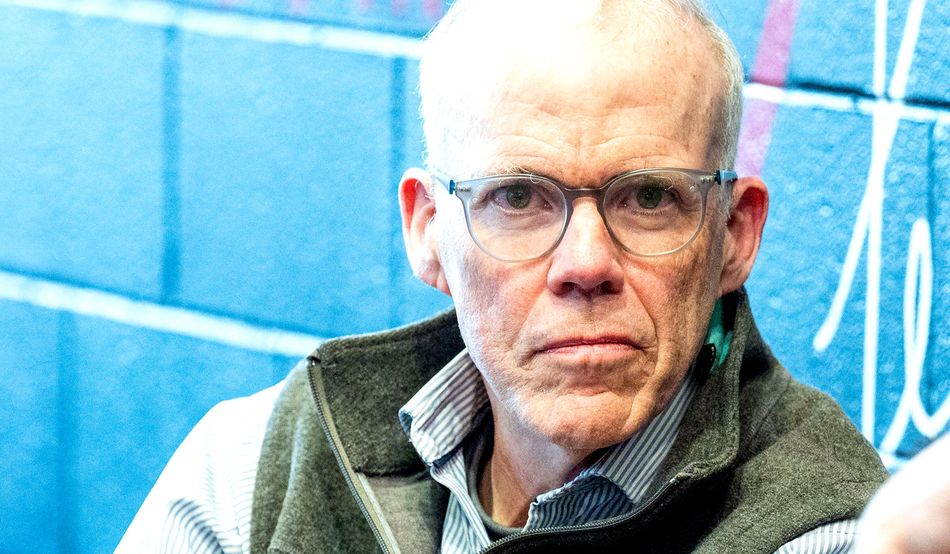

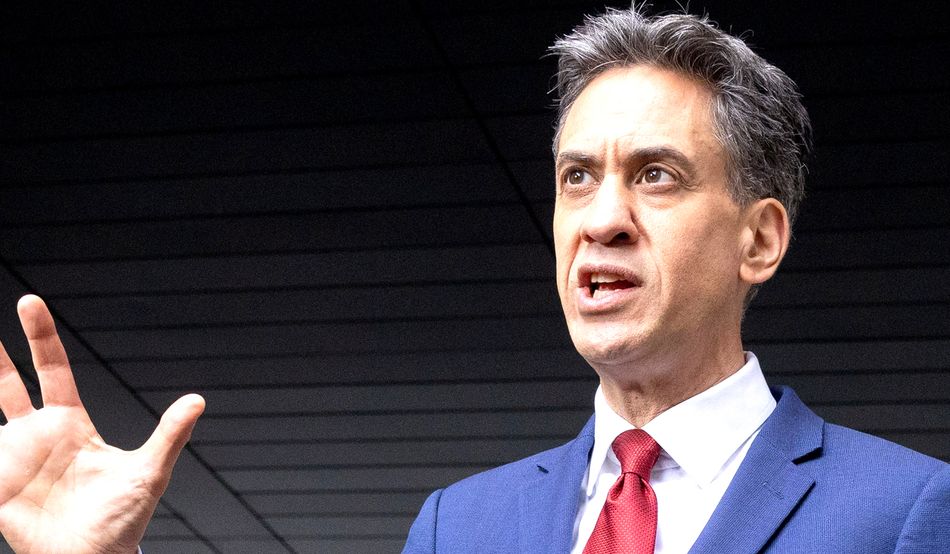

According to the UK’s climate minister and a leading American environmentalist, though, the economics of electrification will make the future brighter than it first appears. Ed Miliband, secretary of state for energy security and net zero, and Bill McKibben, an environmentalist and author, joined Wolfgang Blau, Prospect editorial board member and cofounder of the Oxford Climate Journalism Network, to discuss political strategies, positive tipping points and the fight that’s still to come. The conversation took place at the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero and online on 2nd December 2025.

Wolfgang Blau: In November 2024, British prime minister Keir Starmer said climate action was “not about telling people how to live their lives… I’m interested in making sure their energy bills are stable, that we’ve got energy independence and that we also, along the way, pick up the next generation of jobs.” My starting question is: do you both agree with that statement?

Ed Miliband: Shall I start, Bill? I do agree, it will surprise your listeners and viewers to know! I mean, I’m in this unusual position of doing a job I did 16 years ago, for the second time (for those who don’t know, I was the climate change secretary from 2008 to 2010). And what’s so interesting to me, and this is partly because of the way the world has changed, is that the argument we’re making is now not simply about doing the right thing for future generations, but it’s about doing the right thing for today’s generations. We’re not just in the disaster avoidance business, we’re in the better lives today business.

For me, this is really fundamental because the argument now to transition away from fossil fuels is an energy security argument. It’s a lower bills argument, because look what happened to energy bills in this country when Russia invaded Ukraine. It’s an argument, as Lord Stern says, about the greatest economic opportunity of the 21st century, and who is going to seize it. And of course, it is also crucially about the legacy we leave to young people and future generations. Some of us did make this argument way back then, but I think it is now a more convincing argument to make, for a variety of reasons, including the dramatic fall in the costs of solar and batteries and wind and so on. I think that’s why this transition is unstoppable, because the economics and what’s right environmentally now point in the same direction.

Bill McKibben: Ed’s in a really interesting position, because he’s one of the first people, in the western world, anyway, to attempt to implement policy in a dramatically changed world. The first 35 years of the climate crisis were spent on a planet where fossil energy was relatively cheap and clean energy relatively expensive, and that constrained all the action. Pretty much everything we were doing was in some way to try and make fossil fuel more expensive, so we’d use less of it: pricing carbon or slowing down the infrastructure buildout or divesting from fossil fuel.

As of three or four years ago, that has flipped, and now the force of economic gravity works in the other direction. So the prime minister’s point is powerful.

The other thing that’s happened is, we’re 10 years further down the pipeline in the climate crisis, and the amount of time that we have left to deal with it has correspondingly shrunk. The secretary of state is saying just the right things about how to think about this politically, as long as everyone is also remembering in the back of their minds that the latest data on things like what the big currents in the Atlantic are doing is pretty daunting. We’re going to end up in the right place—30 or 40 years from now, we’re going to run the planet on clean energy just based on sheer economics. But the job is to speed up that transition, in the hope that we might get there before it’s a broken planet that we’re running on clean energy.

Ed: Bill, you are right, and there’s two truths that we’ve got to hold, aren’t there?

One—and personally, I have come to think that this is more important than I used to think it was—we have made progress as a world. After I left the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009—which went badly, for those who don’t know—we were heading for 4°C of warming by the end of the century, and now we’re heading for somewhere between 2.3 and 2.5°C if countries meet their emissions commitments. That’s very bad. Deeply serious in the ways that you’ve talked about, very catastrophic for future generations. But we have made progress as well.

The second truth is that we need to speed up. We’re way off track from where we need to be. And holding both those truths is one of the challenges we both face, maybe in different ways, because if you hold only the first truth, you’re not telling the truth, and if you hold only the second truth, you make people despair and think, “Well, you’ve been going at this for decades and you’ve made no progress.”

Bill: We’re moving, potentially quite quickly, into a different kind of world

Bill: I think it’s a super-exciting moment, and we haven’t done as good a job yet at transmitting that excitement as we should. In the United States, we did this big thing in September at the equinox. We called it Sun Day, and we had 500 events around the country just to celebrate possibilities. And I think that for politicians that should be getting easier and easier.

One of the fundamentally fascinating moments of the next year is going to be that, from July 2026, Australia will start offering three free hours of electricity to every Australian, every afternoon in three states. Humans have spent 700,000 years working hard to get the energy they needed, collecting the firewood, paying the electric bill, whatever it is. We’re moving, potentially quite quickly, into a different kind of world, and if we can summon some of that excitement, it’ll make it much easier to get there at the pace that we need to go.

Ed: My friend Chris Bowen, who’s the Australian climate minister, never ceases to talk about his three hours of free electricity. And to use a sort of fashionable word in some US circles, it does offer the possibility of energy abundance, doesn’t it? That is what is so exciting about this.

I was with some people earlier on today who are talking about eight-hour batteries. I believe Gavin Newsom is doing this in California. Normally people say, what happens when the sun doesn’t shine or the wind doesn’t blow? Well, actually, if you can get to eight-hour batteries, you’re beginning to get to the point where it can be 24 hours. And this is what the UAE is talking about doing.

Bill: It’s absolutely right, and it’s completely fascinating. The next time you talk to your Australian counterpart, just remind him that this is all great, and if you’re also exporting vast quantities of coal off to Asia, you’re undercutting the moment too. Moments of transition are incredibly complex and this is one where we’re going to have to keep as much pressure on as we can, because the time is so compressed that we don’t have the luxury of doing what we like.

Wolfgang: I would like to tap into the shared expertise of both of you as leading climate communicators. You, Bill, effectively developed the genre of climate journalism before the term even existed. You, Ed, developed some of the world’s most innovative climate and energy policies. How do you communicate the economic advantages of climate action and the energy transition, as well as the growing emergency and risk from increasing extreme weather events in countries, both the US and UK, where a large share of your audience are increasingly worried about their rising energy bills?

Bill: I think we start where we just were. If I were running for office in the midterms in the US—which is going to be a pretty critical election, and which may determine how far down the road we go with whatever offbrand of fascism we’re experimenting with—I think I’d be talking a lot about what’s happening in Australia. And I’d be contrasting it with what happens when you, as we’re doing in America, increase the demand for electricity with every data centre anyone could ever want to build, and when you constrict the supply of the cheap stuff. Everybody can understand “free”. I think people increasingly understand the possibilities that clean energy provides. So I would spend a lot of time talking about that. I’ve been out campaigning all fall and my sense is that people really understand, if you explain it to them, that we’re in a new moment—and it helps that everybody hates big oil companies and the like. They understand that the companies have been doing nothing but try and preserve their own business model for two or three decades now.

Ed: For me and for Britain, I think, the seminal moment in this was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. People saw their bills go through the roof, and people understood that wasn’t because we were importing lots of Russian gas (I think it was something like 4 per cent in the UK, if that) but because gas was priced on the international market, and we were a price taker, not a price maker—in other words, British fossil fuels don’t make the price of fossil fuels. By two to one, still, if you ask the British people whether they think renewables or fossil fuels will get you cheaper bills, they say renewables.

I think about it two ways. One, if we’re going to lower bills for good, we’ve got to lower the wholesale price of electricity, and the way to do that is with renewables. No question; even our critics don’t take that idea on. Now they talk about the cost of building, and we’ve got to bear down on those costs of building—but the way to lower these bills for good is through cheap, clean renewables.

But the second point is a sovereignty point. I think people really understand that fossil fuel dependence is a massive gamble on international geopolitics. Something goes wrong in the Middle East and prices go up. Putin invades Ukraine, and you’re at the mercy of petrostates and dictators. Why would you want that when you can have cheap, clean, homegrown energy, which is the right thing for future generations and the right thing for today’s generations?

There’s this Westminster view that there’s a massive backlash against net zero. But what all of the polling people tell me, those who I trust, is this is wildly overdone. There are very loud right-wing newspapers that are talking about this backlash. There are loud people on X saying the same. We’ve got to make sure that people see reductions in their bills, which is why the Chancellor announced a £150 reduction in costs from bills in the November budget. And that’s really important, because we’re determined to show people that actually we can tackle the cost of living crisis at the same time as moving to clean energy.

Bill: The first point that Ed was making hasn’t yet sunk in enough. A world dependent on fossil fuel is dependent on people who control the few places where we have big pools of this stuff. That’s the world that we’re accustomed to living in, but it’s a bad world.

Vladimir Putin is a good example of these people, so is the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, and now so is the president of the United States. The idea, as he’s put forward, is that we’re going to have energy dominance by forcing everybody to buy American liquefied natural gas (LNG), if they don’t want tariffs. That should be and I think is serving as a strong reminder to the rest of the world that, though they may not like everything about China, they’d just as soon buy some green gear from Beijing and then depend on the sun henceforth, and not depend on anybody else.

To put it in reverse, I often ask people just to reflect on how the geopolitics of the world would have been different for the last 100 years if oil had been of relatively trivial value during that time. How many wars and coups and assassination attempts and terrorist plots and everything else we would have averted. That’s the world that we’re now more or less capable of creating, because every place on the planet is going to be capable of producing its own energy.

Wolfgang: It’s almost impossible to disagree with either one of you. We all know that no state in the US installs more renewables than Texas, exactly because money talks and they are much more affordable.

However, there is a paradox that I think we really need to address more in this conversation, and that goes as follows. In survey after survey, we see the population of the UK, urban as well as agricultural, as well as people in the US, say they are worried about climate change. They can see an increasing number of impacts, they want much more aggressive policymaking by governments. And yet we know what the election results look like in the US and here in the UK. We all know Reform is leading, ahead of any other political party with sometimes double-digit margins. What is this paradox, this populism versus the planet? How do you make sense of that contradiction?

Ed: Well, I would bow to Bill’s knowledge on this, but I don’t think Biden lost because of his climate policies. I haven’t seen any evidence that suggests that. And what people who know about this tell me is that in the UK, as I say, the argument about the backlash is overdone.

Look, in a sense, it’s a fight. And as a politician, I think, “let’s have the fight”. Because Reform have said they want to wage war on clean energy investment. We’re going to double the number of clean energy jobs by 2030—that’s 400,000 jobs that they are waging war on, as well as the existing clean energy jobs. You’re seeing those jobs spring up all around the country. Well, let’s have the fight about whether we’re better off betting on expensive, insecure fossil fuels and dependence on that. Personally, I think we’ll win the argument.

Ed: I don’t think Biden lost because of his energy policies. I haven’t seen any evidence of that

Rishi Sunak, who was the prime minister here, gave a big speech about a year before the last election, basically rowing back on net zero. It didn’t really help him. Boris Johnson said the other day that his party had basically decided to declare war on net zero, and he didn’t think it’s going to work. So, I can’t speak for the US but, as far as the UK is concerned, I don’t think people really want a culture war on this. And I think the Tories and Reform are making a big mistake. As a Tory actually said to me recently, it’s bad policy and bad politics.

Wolfgang: So the polls are wrong?

Bill: The polls are right. But people are not lining up behind Reform because of their position on energy and climate. Politics is determined by 1,000 moving pieces at once, and the good news for Ed and company is they’ve got three years to solidify what they’re doing.

The lesson from the Biden administration is that you’d better be good at talking about what you’re doing, as well as doing it. Biden actually did good work around energy and climate, but did poor work around messaging on any of it. Our election wasn’t decided by any of that. It was decided by 1,000 things having to do with people’s perceptions about the age of politicians and whose vibe was what, and the kind of things that often determine elections.

Ed is the right person to be doing this, because he’s capable not only of getting the policy right but of making the case. Over the next three years, given time to solidify what’s starting to happen in the UK, there are going to be a lot more people earning their living out of the green energy sector than out of the fossil fuel sector, and it’s going to be Reform that’s taking bread out of people’s mouths. If it works right, you can get things set up so that communities really benefit from clean energy when it goes in.

Wolfgang: There’s an interesting phenomenon across Europe, whether you look at [National Rally parliamentary leader] Marine Le Pen’s people in France, Germany’s AfD, prime minister Giorgia Meloni in Italy, to a degree Sweden and here Reform, which is that they have very different policy positions on the EU, the euro. Even on migration, they really differ. Yet what they all share, passionately so, is their support for fossil fuels and their resistance against renewables.

Ed: Is that really true? I don’t want to contradict you as you know a lot more about European politics, but I had a discussion with my Italian counterpart at COP who I think was part of conservative Forza Italia at one point, and he was talking about all his schemes on solar, rooftop solar, other things he was doing. Is it that black and white?

Wolfgang: If we stick with Germany, where we have several regional elections coming up next year, the vehemence with which AfD is fighting renewables is striking. It’s an open question, it’s not a given, right? What makes fossil fuels so attractive to right-wing nationalist parties?

Bill: There are going to be a lot more people earning their living from the green energy sector than fossil fuels

Bill: Reactionaries are comfortable in the past, and the past was the time of fossil fuel. Reactionaries are comfortable with big concentrations of wealth and power. The very first plutocrats on planet Earth were people like John D Rockefeller, who figured out how to corner the market on petroleum. I don’t think it’s any huge surprise, but I doubt whether that becomes a hugely effective weapon.

If you look at what else has been happening across Europe, how many millions of people in the last three or four years have put solar panels on their balconies? A kind of incredible gateway drug into the world of control over energy.

I’ve lived my life in rural America, which means I have a lot of neighbours who have a Trump flag on the mailbox and a solar panel on the roof, not because of climate, but because “my house is my castle, and it’s a better castle if it has an independent power supply”. So if we learn to talk about these things in some new ways, then there’s a real chance of bridging some of these divides.

Ed: I don’t want to sound complacent about this, because I’m really not. This is definitely a big fight. I’m partly saying what I’m saying because I believe we can win it, and also partly because I think we’ve got to win it, frankly. I think you can win the argument as long as you begin by understanding that, for so many people in the UK and in the US, the affordability or cost of living crisis is their number one issue. And recognising that it is totally understandable that that issue, for many people, trumps all others. That is our starting point when it comes to our advocacy for clean energy, in creating the good jobs, in cutting bills and all of those things.

Ed: Nigel Farage said he wants to bring back coal mines. Nobody in my constituency wants that

Wolfgang: What does a general population need to know? How technical do you both need to be in your public communication? Climate change is sometimes described as a two-term problem—of course, it’s much more—but what we see is that candidates and parties such as Australia’s teals [independents] get into parliament as surprise winners on a climate ticket, or in the case of Germany the Greens became part of the coalition, but as soon as they start doing what they promise to do, they lose the support of their own voters and are out again.

Bill: The technical stuff you need to understand and be able to communicate now isn’t about climate. Most people understand that we’re in a fix here. They don’t understand exactly what we’re going to do about it, because no one understands exactly what we’re going to do about it. What you need to be able to talk about are heat pumps, EVs or ebikes. You need to be able to talk about insulation. And happily, most people are fully capable of understanding those things. If we master and win that discussion then the other stuff begins to take care of itself.

Ed: You don’t need to convince people that climate is having an effect. I think that’s true in the UK and in most parts of the world.

Reform leader Nigel Farage said he wants to bring back coal mines. I’m from an ex-mining constituency. Nobody in my constituency wants to bring back coal mines. I’ve been an MP there 20 years! I literally could count on the fingers of one hand the number of people who’ve said that to me. What they do want is the good jobs, like the dangerous, precarious, difficult, sometimes fatal, but good jobs with pensions and security and community, that coal mining used to provide. That’s where clean energy is our absolute best bet.

Bill: Often kids ask me, what job should I do in order to help the planet and to have a good life? And you know, I often now say, look, if you’re at all good with your hands, the most useful job on the planet right now is electrician, and we need a lot more of them, at least in this country. There’s going to be no shortage of demand for decades to come, and you’re doing the thing that’s actually essential to changing the planet.

Wolfgang: Ed, I’d like to speak a bit about China. We hear a lot about this new multipolar world with various power blocs: China, India, the EU, Europe, the US. But in many ways, we’re also entering a quite binary or bipolar future of a rising electrostate and a United States that’s doubling down on being a fossil fuel power, trying to force even Europe into greater dependency on fossil fuels again. What is your view on the emerging role of China here? Bill, you wrote recently that China was working to own the future. Personally, as much as I respect what China is doing for the energy transition, that quote worries me. I wonder if it doesn’t worry you that China could be owning our future?

Bill: I’m well aware that if I had spent my life doing in China what I’ve spent it doing in the United States, I would have spent my life in jail. So, it’s not like I’m a huge fan of the Chinese regime. On the other hand, they’re a nation looking rationally at the future around them. They faced an extraordinary problem, in that their cities were becoming essentially unliveable from pollution, and in a matter of a few years managed to turn that around, in the process building an industry. They’ve made their bet on this electrostack of technologies, where the United States has made its bet—I think an unwise one—on AI as our driver for the future. I think it’s unwise, if only because there are no guarantees around AI the way there are around the factories that are churning out the stuff in China.

In any event—I can say this, and Ed can’t—I think it’s been remarkable to watch, over the last nine months, a country surrender technological and economic primacy. All this stuff was invented in the US. The first practical solar cell: 1954, Bell Labs, Edison, New Jersey. The first industrial wind turbine: 1941, 30 miles south of my house in Vermont. The lithium-ion battery, on and on and on. And we’ve now tossed this away.

Our president went to the UN and gave a speech which I think is perhaps the dumbest speech in the history of the UN (not a high bar to clear, it must be said) in which he explained that green energy doesn’t work and that climate change is a con job and a hoax. The short-termism of the US in regard to this is breathtaking, and it is rewriting the geopolitics of the world. You could sense it [at COP30] in Belém, because from that technological and economic primacy is naturally going to follow a kind of political leadership.

The difference is, if you go get green technology from China, you buy it once, and then you depend on the sun and the wind. That’s a very different prospect than going to Russia or Saudi Arabia or the US and buying LNG, which you then set on fire and have to buy some more of tomorrow. One is renting forever and the other is buying to own, at which point you then depend on the sun, which has had heretofore an enviable record of coming up pretty much every morning.

Ed: It would be negligent not to engage with China, the world’s largest emitter

Ed: There’s plenty of reasons to be cautious about China: its dominance of the economic supply chain, and a number of other reasons. But what really struck me about COP30 in Belém is that of all the countries there, I would say China was one of the most keen on an agreement. They have set their faith in these multilateral processes.

The way I think about it is that it will be negligent not to engage with the world’s largest emitter. And also, I don’t want to sound like a sunny optimist about everything, because I think there are huge challenges and I wish China’s target was more ambitious, but if Bill and I had been talking 15 years ago, and if we’d said China will have an absolute cut in emissions by 2035, as they do in their NDC [Nationally Determined Contribution, each country’s agreed reduction in national emissions under the Paris agreement], I don’t think we would have believed it.

Bill: And their carbon emissions are down year-on-year. They’re going to beat their target, I think. More to the point, they’re driving down everybody else’s.

I haven’t been to China for the last couple of years, but people there tell me Beijing and Shanghai are way quieter than they were a year ago because everybody’s driving EVs. That’s good news for Beijing and Shanghai, but the real news is for the rest of the world. Anybody counting on fossil fuel growth, for example if Reform wants to go drill in the North Sea, there’s not going to be a market for it. China is leading this transition away.

The other piece of good news is that there’s nothing stopping anybody else from setting up factories to build solar panels. And indeed, lots of people now are. I think the big action in the next few years is going to be watching the Indians figure out how to jump into this.

Ed: Yeah, 100 per cent. The fact is, Trump did say he was leaving the Paris agreement, and people wondered if there was going to be a domino effect. I don’t say in any way that the agreement that was reached in Belém was perfect. Far from it. But 194 countries said, “We’re going to keep the show on the road. We believe in multilateralism. We do believe in Paris.” I think there is a significance to this.

Bill: A bunch of countries signed up to join Colombia and the Netherlands in talking about fossil fuel transition in the spring, you know.

Wolfgang: Ed, you led negotiations, you led ministerial consultations, you were part of the group of countries, together with France and many others, to demand the inclusion of a roadmap to transition away from fossil fuels. Can you describe the minimum elements that such a roadmap needs to include?

Ed: It was very important to COP28, in the UAE, that there was a commitment for the transition away from fossil fuels. One of the things I said at COP30 is that we should have this roadmap not because it’s easy, but because it’s hard. There are complex issues, let’s be honest, for fossil fuel producers and the implications for their economies; for fossil fuel-consuming countries; for making sure there’s a just transition for workers, a whole range of things.

A commitment to transition away from fossil fuels wasn’t in the final text from COP30; there was a reference to the UAE consensus of COP28 which we got inserted at the last minute. But what’s so interesting about what’s come out of Brazil is that something like 80 countries from the Global North and Global South—which goes to this point that lots of countries are thinking, this is in our economic interests—have now signed up to wanting this roadmap to phase out fossil fuels. The Brazilian presidency will now work with us and others on what this roadmap looks like, and how it starts to chart this complicated course to what this transition away looks like. Again, I think it’s a hopeful sign.

Bill: Just in the same way that the economic force of gravity has kind of flipped, I think the COP process is now trailing the economics of the energy transition, and its job is going to be to figure out how to clean up as that transition goes on, how to make it possible, smooth it, accelerate it. In climate terms, the whole COP process hit its high watermark at Paris, and that’s that. I don’t think there’s a scenario where COP drives climate consciousness forward in a relevant timeframe, but it can play a part.

Wolfgang: What does drive it, Bill?

Bill: Events drive it. If anybody thinks for a moment that people’s understanding of climate change is going to go away, they need only wait for the next round of floods, hurricanes, wind storms, fire storms, whatever else.

The other thing that’s going to drive it is the understanding that we now have a tool that we spent most of the climate era without. As of three or four years ago, we have—in the form of cheap sun, cheap wind, cheap batteries—a tool, and it’s the only tool that we’re going to have in a relevant timeframe. Twenty-five years from now, we may have small modular reactors, but in the period of time that decides whether or not we break the back of the climate system, we have sun and wind and batteries, and that’s good.

I think international diplomacy will be about figuring out how to deal with that transition; other things are driving it forward.

Ed: I’m a bit of a defender of the COP process, partly because I think we’d never have got from 4°C to 2.3°C or 2.5°C, or to 80 per cent of the world being covered by net zero targets without this mechanism of accountability. It’s a frustrating, mad system, but it is 194 countries trying to navigate their futures. So it’s not surprising that it’s quite complicated!

I think it’s good that Keir Starmer went, and leaders continue to go, because it does provide them with some kind of mechanism of accountability. But I sort of agree that what’s happening in the real economy, which was quite on show at COP, is the most exciting thing, because you can see the transition actually happening.

Wolfgang: Bill, I have to ask you a more personal question. You have been at this for quite a long time. Thank you very much. At the same time, every time you almost had a breakthrough, a policy change happened, a new government happened, and you almost went back to square one. Does one need to sign up to a life as Sisyphus to work in climate?

Bill: That’s not really how it feels to me. It feels to me, as I said, as if we got to the top of the hill, to use your image, and the ball is now rolling, finally, in the right direction. The job is not Sisyphean. The job is now to push that ball as hard as we can.

The problem is that we wasted 30 years, mostly because the fossil fuel industry gamed our political system… most of the advances that we’ve made in technology, we could have made 20 or 30 years ago. We never get that time back, and the planet and its people are infinitely poorer as a result. But it doesn’t do much good to whine a lot about that. The job is to figure out now how to take advantage of the fact that we finally have a tool, because it would truly be a sin to waste it.

I use the word “sin” advisedly. I was in Rome in September with the new pope—a weirdly normal American, I must say. Very strange to see in operation. And he was great. He said the path that Francis has set out is the path that we will keep following. The Vatican recently became the first solar-powered nation, having flipped the switch on this big, new solar farm that they’ve built. I said that our slogan henceforth has got to be “energy from heaven, not from hell”. We’ve got to ride renewable energy as hard as we can. We’ll see where it gets us. And it’s completely possible that, by 2030, we’ll look around and we’ll have to take other drastic action, because the physical trends we see on the Earth, around the Atlantic currents, around the jet stream, around the savannafication of the Amazon, will have pushed us even harder than they’re pushing us now. But we will be in a much better position to take whatever action we need to take if, between now and 2030, we’ve built a hell of a lot of solar panels and wind turbines and batteries.

Wolfgang: I share all your excitement about the technologies that are now finally at our fingertips and available at ever lower cost. I do worry, though, about one thing: these ever more frequent policy swings.

Labour’s 2030 climate and energy strategy, of course, is banking on very large infrastructure investments for which investors need to have trust and policy certainty. And yet we see it in Brussels on the issue of the automotive industry combustion engine bands, we saw it in the US; a lot of investment has been destroyed. How do you reassure investors that there is enough policy certainty to follow your strategy, which many of them really want to support?

Ed: As far as we’re concerned, investors have a clear sense of our mission and have faith in our mission. I’ve been struck actually by the extent to which you can get people to buy into this argument. By staying the course and showing the progress you can make, I’m confident that we can do that.

I have a few thoughts that come from what Bill said. I mean, if the Vatican could do it, everyone can do it. If the Vati-can, anyone can, boom boom!

A few thoughts. One, 1.5°C absolutely matters, and we should keep 1.5 alive. But it’s also the case that every fraction of a degree matters.

Secondly, we talk rightly about negative tipping points, but there can be positive tipping points. If you look at what solar has done in the last 10 years, it’s way exceeded the forecasts of the International Energy Agency and others. And I think we can see positive tipping points as these technologies become cheaper and you get greater deployment than you expect.

Thirdly, I suppose the most important message for me is: don’t despair. Despair is a completely futile thing, and part of the responsibility in all of this, and I think Bill does this very well, is to be a bearer of hope. I don’t feel despairing. I feel that what is happening is daunting and deeply worrying. But I feel hopeful. And I genuinely think there are reasons for hope.

Wolfgang: Optimism is the job.

Bill: I agree with that. It’s easy to be despairing right now, especially in the US. We’re in the grip of an illiberal and in many ways dangerous but farcical administration, but people are rising up and demonstrating that they don’t like it. I think, knock on wood, that some sense will be restored here eventually.

At any rate, climate change is about what happens on the planet, and on the planet things are headed more in the right direction than they have been at any point in this period.

Bill: Our job is to save as much as we can of the world we were born into

What Ed says is the bottom line is absolutely right: to the best of our understanding, every 10th of a degree Celsius that we raise the temperature moves 100m of our brothers and sisters out of a safe climate zone and into a dangerous one. So the fact that we can’t stop global warming is sad, but the fact that we are in a position to save hundreds of millions of people from having to leave their homes should be more than incentive enough to keep everybody at work.

As for investors: look, anybody who’s serious about looking at the future and understanding which way it’s going has got to reach the conclusion that the human experiment with setting stuff on fire is coming to an end, and human reliance on the sun—which already gives us, remember, light and warmth and, via photosynthesis, our supper—is now moving into an entirely new phase. In the longest historical sense, that’s the meaning of our moment here, and our job is to accelerate that transition such that we save as much as we can of the world that we were born into.

Wolfgang: In closing, a question to both of you. You touched upon climate tipping points very quickly. What are the signs and signals we should watch out for as indicators of positive tipping points towards humanity embracing a climate-positive future?

Bill: The fact that every Australian is going to get three free hours of electricity, beginning next year, is one of those moments that historians will one day use to dramatise the moment that we’re in.

Ed: It’s every local solar project, wind project, nuclear, in my view—you see it around the world. I genuinely believe this transition is unstoppable. And Bill said it earlier on, the transition is unstoppable, the question is: can we do it in time and quickly enough? Acceleration is what it is all about. And there are countless reasons for hope and optimism and positive tipping points.

Wolfgang: Ed, Bill, thank you both very much.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity