Since the dawn of the industrial age, energy security has been defined as a reliable supply of fossil fuels at a stable and reasonable price. The pursuit of it has seen countries invaded, regimes toppled and civil wars prolonged in repeated battles to control fossil fuel assets—from the British military operations in Iraq in 1914 to the recurring gulf wars of recent times.

Ahead of a summit held in London in April this year and sponsored by the UK government and the International Energy Agency (IEA), an alternative understanding was proposed. A roll call of more than 130 clean energy companies, industry associations and investors produced a joint statement urging governments to redefine the meaning of energy security. It was clean energy that would provide jobs, cut costs and make Europe and the UK more secure, they suggested. And it was clean energy that would protect businesses from price shocks like the one that followed Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022; it added one trillion dollars to unplanned expenses for industry. “A vision of energy security based only on the security of fossil fuel supply is no longer compatible with protecting businesses and consumers or sustained economic growth,” they concluded.

Even allowing for the vested interests of the signatories, this was a radical statement and an appealing view of energy security in the electric age: a promise of peace, stable prices, reliable and abundant clean energy and long-term prosperity.

In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion, it was anxiety over energy security that added further urgency to the transition away from fossil fuels already initiated to meet the climate crisis. But already by 2020, China’s mastery of supply chains and high-volume production had brought the cost of renewable energy installations down so dramatically that it was cheaper to build renewables than new power stations powered by oil or gas. Innovation in storage promised to address intermittency and balance supply and demand in grids, popular acceptance of renewables was growing and governments around the world were planning the upgrades of national grids needed to manage the variable supply of renewable energy.

As the IEA noted in its 2025 report, three years after the Ukraine war began, the countries that had achieved a rapid growth of renewable technologies since 2010 had reaped the benefits of becoming less dependent on imported fossil fuels. Growth in renewables across the European Union overall had reduced such imports by 50 per cent, and helped the bloc to survive the 2022 energy crisis caused by the Kremlin. And yet, despite the continuing war and blatant Russian intrusions into Nato airspace, Russia still supplies 18 per cent of Europe’s gas and several governments appear to have entered an age of hesitancy over their continuing commitment to rapid decarbonisation.

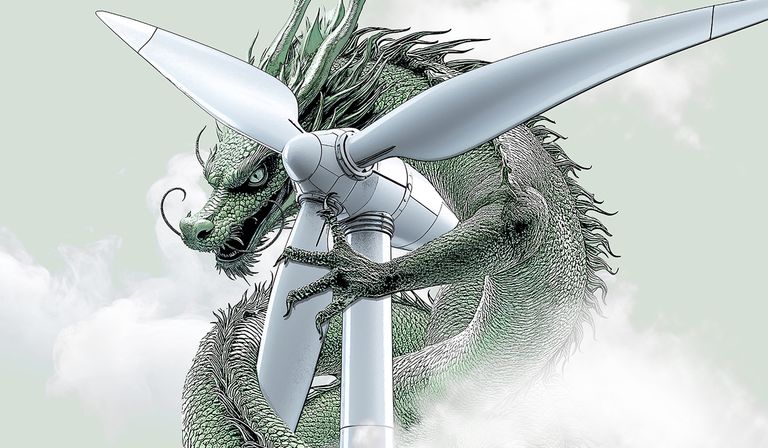

China is now by far the world’s dominant supplier of clean technology. It has destroyed Europe’s solar industry

Some of this retreat can be attributed to the growth of climate-hostile right-wing populism and pressure from fossil fuel industries. But new security concerns about the risks of renewable technologies in an increasingly unpredictable world are also challenging the serene picture offered by the clean energy companies. If security concerns of the fossil age continue to focus on Russia and the Middle East, the anxieties of tomorrow are centred on China.

Unlike the United States, China doesn’t have big fossil reserves to exploit or promote, with the exception of coal. Having become a net importer of oil in the 1990s, its energy security headache is the need to import large quantities of oil and gas, most of it by sea. Leaders in Beijing realised that a transition to clean energy not only suggested a solution to this vulnerability but also a massive opportunity at a moment when China’s industrial production needed to move up the value chain. They acted, investing heavily and consistently in energy transition technologies since 2011, the beginning of the 12th Five Year Plan.

As an industrial policy, this has been a domestic success, but China’s low-cost and abundantly available technologies are accelerating the spread of clean energy around the world. China is now by far the world’s dominant supplier of clean technology. It has destroyed Europe’s solar industry and now builds 80 per cent of global solar capacity. In 2020, it took the leading position in wind power manufacturing from the EU. Just three years later, China held approximately 60 per cent of the world’s wind turbine production capacity, compared with the EU’s 19 per cent. For the first time, four of the world’s top five original equipment wind manufacturers that year were Chinese.

The availability of clean, affordable renewable technology is helping to resolve traditional security concerns over imported fossil fuels and making a rapid transition possible. In this year’s energy forecast, the IEA expects that electricity generation from renewables will have increased by 60 per cent by 2030, and by the end of 2025 renewables may pass coal to become the largest source of global electricity. Solar photovoltaics (solar PV), which convert sunlight into electricity, are expected to account for more than 50 per cent of this increase, followed by wind, with a likely 30 per cent share. Renewables are projected to meet more than 90 per cent of electricity demand growth in the next five years.

But this renewables surge has given birth to a new and even more challenging security issue. Unlike oil and gas, renewable energy supplies—wind and sunshine—are entirely local. The new problem is that such energy systems must be digitally controlled. Since China is the dominant supplier, the question arises: could that control be exercised to benefit Beijing?

Unlike traditional electricity systems, which typically rely on centralised power stations, renewable energy systems are networked and incorporate energy inputs from various solar panels, wind farms and battery storage. This means they need advanced digital technologies and platforms to coordinate the flow of power and maintain grid stability. While this digital management makes energy use more efficient, it also increases risk. A 2024 report from the FBI warned that renewable energy systems brought novel vulnerabilities and increased the number of entry points for a cyberattack. At the centre of those increased risks is the indispensable technology of the inverter.

Inverters are both the brain and the musculature of renewable energy systems. They convert the energy generated from direct current (DC) to grid-friendly alternating current (AC) and allow the user to monitor and manage performance. At a household level, the inverter reports how much energy is generated (for example, by domestic solar panels) and sends alerts if problems arise. At utility scale—a large wind or solar farm—inverters manage the relationship of the generating technology to the grid, reporting minute by minute both on their own output and on grid demand, to determine the energy output that the grid can accept at any moment.

This is critical to making renewable energy usable. If a wind farm is generating more than the grid can absorb, the inverter manages the imbalance and supply is curtailed to avoid crashing the grid. But the smarter the inverters, the more data they process and, according to security experts, the greater the risk of a range of cyber threats: penetration by cyber criminals, malevolent hostile state attacks or manipulation. While inverters are controlled by their operators—a British energy company, for example—they remain available to their manufacturers for software updates. According to SolarPower Europe, an industry association, 80 per cent of the inverters imported to Europe come from China.

In February this year, Nato published a sobering assessment of the risks to national energy systems and cyber security that are built into renewable energy systems. China, increasingly seen as a technonationalist state that regards technological control as geopolitical power, has established a virtual chokehold on renewable technology and component supply. If it decided no longer to deliver them to Britain, our capacity to generate renewable power would be threatened. For Nato, however, the greater risk is not in the supply of components but in their operation.

Assessing national security risk involves imagining the worst that could happen, evaluating the probability of that event and putting necessary security measures in place to prevent it. In the unlamented “golden era” of UK-China relations, David Cameron and George Osborne overruled security concerns to invite China to build and operate a nuclear power plant in the UK. They appeared prepared to take this risk in the belief that China would never exploit its position on the grid to do harm—but in 2022, their successors in government spent £700m to buy China out of the Sizewell C nuclear power venture in Suffolk on security grounds and quietly killed off cooperation on future nuclear projects.

In the colder light of 2025, three years after Russia and China declared their “no limits” friendship and the Ukraine war that followed, the naivety of Cameron and Osborne seems unthinkable. Earlier this year, China’s foreign minister Wang Yi told an EU delegation that Beijing could not let Russia lose the war in Ukraine. Beijing already provides Russia—named in this year’s UK national security strategy as the “most obvious and pressing threat”—with drones, as well as semiconductors, microchips, critical minerals and other components of military equipment. Joint military exercises between the powers have also become more frequent. Wang Yi’s statement must make governments that support Ukraine question what else China is prepared to do to save Putin from defeat.

Russia’s almost routine assaults on Ukrainian critical energy infrastructure are instructive. The Kremlin launched a combination of physical and cyberattacks on the Ukrainian electricity grid in 2022, and has repeated such hybrid attacks against its energy infrastructure ever since. But Russia began its cyber-attacks on Ukraine’s electricity systems in 2015, when it planted malware that rendered computers inoperative and spread to the industrial control systems of energy companies that were connected to the internet. The malware also erased the files needed for system restoration. Approximately 225,000 homes lost power.

The next year, another attack built on those tactics and brought down the systems that shielded essential grid equipment from electrical faults. It forced Ukrainian grid operators into a risky recovery effort “without full visibility of essential systems, putting grid equipment at risk”, according to a US Congress report. Washington has attributed these attacks to the GRU—Russia’s military intelligence directorate.

Since the war began, national security agencies have also noted increased cyberattacks on countries that support Ukraine by Russian state-sponsored hackers with such colourful nicknames as Berserk Bear, Energetic Bear, Crouching Yeti and Dragonfly.

Beijing’s continuing material and diplomatic support for Russia’s war has forced a reassessment of the risks posed by China’s involvement in national energy systems. Chinese-made equipment is already deeply embedded in national power grids in the US, the UK and Europe—a troubling fact when considered alongside the record of covert Chinese cyberactivities. As far back as 2010, the US defence department discovered that its computers were sending military network data to China. Since then, there have been repeated discoveries, including the notorious Volt Typhoon, a Chinese state-sponsored hacker group that was found in 2023 to have compromised thousands of American computers. Washington and its Five Eyes intelligence partners issued a warning in 2024 about the group’s targeting of critical infrastructure.

Richard Dearlove, former head of MI6, said the UK’s net zero target ‘hands power to Beijing’

China has repeatedly denied involvement in offensive cyberespionage, but security analysts believe that Volt Typhoon was a multi-year operation to install disruptive technologies that could be used in a moment of tension, such as an invasion of Taiwan. When the need arose, it would give China the capacity to disrupt communications across the US, along with potential sabotage of critical infrastructure including electrical utilities, water systems and transport hubs.

Worrying recent discoveries suggest renewable technologies—in particular, Chinese-made inverters— could be part of future cyberhacks. While inverters have firewalls designed to block unauthorised access, this protection can be circumvented. In May 2025, American investigators discovered undocumented communication modules embedded in Chinese-manufactured solar inverters and battery systems through which an attacker could switch off or sabotage inverters, remotely disabling or manipulating devices and potentially triggering cascading grid failures.

This is Europe’s problem, too. Over 200 gigawatts of European solar capacity (equivalent to more than 200 nuclear power plants) are tied to Chinese-made inverters. In May, Reuters reported that unexplained electronic components had also been found in equipment imported from China for Denmark’s energy supply network, according to the industry group Green Power Denmark. In January, Richard Dearlove, former head of MI6 and not an enthusiast for the UK’s net zero targets, told the Times that the goal “hands power to Beijing”.

Any inverter potentially carries a risk of hacking but, because manufacturers can enter their own equipment by the front door, using Chinese technology is unavoidably more dangerous. How governments are reacting to the threat can vary depending on their previous experience with China and which alternatives are available. The Baltic states, which have long warned of the threat from their close neighbour Russia, are among the most cautious of the Chinese risk, too.

In November 2024, for example, Lithuania, following a prolonged confrontation with China in 2021 and 2022, passed a law blocking Chinese access to wind and solar farms larger than 100kW (approximately the rate of production needed for a single building), aiming to cut off remote control of energy installations by potentially unfriendly foreign states. Last year, neighbouring Estonia’s head of foreign intelligence warned that his country could be at risk of blackmail by Beijing unless it banned some Chinese technology, such as inverters.

But is a tough response the best defence? Governments are caught between two serious security threats: the one from China and the ever more urgent warnings from climate scientists that the world is approaching tipping points that could trigger catastrophic runaway warming. Rapid deployment of renewable energy is essential to counter the latter, and it is easier to defend against cyberattack than the collapse of the climate system.

Ciaran Martin, the former chief executive of the National Cyber Security Centre, tells me that covert, unauthorised data transfers and data manipulation are “serious concerns”. And “if the equipment has to link back to a central apparatus controlled by a Chinese company in order to work, the risk probably can’t be mitigated”. But he believes that some risks in renewables must be tolerated, pointing out that the capabilities of smart components can be exaggerated, and that there are practical obstacles to turning them into weapons. “Building in targeted malevolent functionality would be very expensive,” he says, “and is unlikely to be done at scale.”

The risks of Chinese dominance of the supply chain, he argues, are also unavoidable. “If you build a whole edifice of wind farms, the Chinese could stop supplying replacements,” he says, “though that is a card that can only be played once, because the result would be immediate decoupling.” On the operational risk, “It might be possible to turn a wind farm off,” he says, “but again, that is a move that is hard to deny and can only be used once.”

The remedy may lie in how energy systems are designed, what safeguards are created and what security conditions are built into any licence to operate. Audits of the software embedded into renewable technology components from anywhere in the world could be made mandatory, and stringent cybersecurity criteria built in from the start. “It is not impossible,” says Martin. “How many civil aircraft have been brought down by cyberattacks? None. Because we don’t allow that to happen. We design safety systems that ensure that it won’t.”

Such stringent standards, however, are not yet applied to wind turbines—a fact that leaves cybersecurity expert Alan Woodward concerned. “Remote monitoring for maintenance gives you the potential to control the equipment, including to switch it on and off. Our grid, frankly, does not cope as well as it should, so it is not hard to imagine that switching a series of turbines on or off [using inverters] could trigger a cascade collapse.”

Private enterprise might be motivated to find a solution. British company Octopus Energy recently announced that it would be exploring the possibility of Chinese firm Ming Yang building wind farms in the UK. Ming Yang withdrew from a large German wind project this August for “operational reasons” after security concerns were raised, but an Octopus spokesperson insisted it is not blind to the security risks and is exploring ways to use its own software to control Chinese wind turbines. The partnership was in an early stage, she said, and it was not clear what Octopus would do if its plan to install and run its own software did not work.

For now, the way forward is unclear—but it is critical that the dilemma is resolved. Failing to mitigate the risks of connected technologies will expose critical infrastructure to attack. But failing to deploy renewable technologies at speed will exacerbate the catastrophic impacts of climate change. The future of energy security just got a lot more complex.