As transport secretary in the late 2000s, I visited a huge battery products factory in Beijing. It mostly churned out mobile phones for Nokia but was developing a new line in fast acceleration electric cars. They had some amazing prototypes which could travel hundreds of miles without recharging.

The company, called BYD (“Build Your Dreams”), was full of engineers and designers trained at British and German universities. It is now a major player in the UK, selling more than 11,000 cars here last month. If it weren't for Brexit, BYD would probably by now have built a factory in the UK on the model of the pioneering Japanese car companies which entered the European market in the 1980s. Incentivising BYD to build factories and research centres here ought to be a key objective of our industrial policy, to mutual advantage, before the rest of the British-based car industry goes out of business. Rejoining the EU customs union would help a lot.

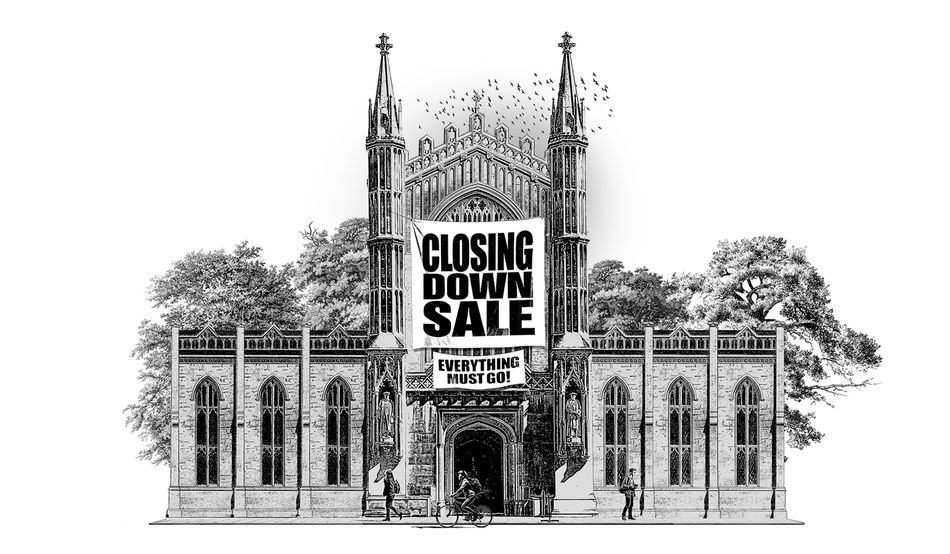

Then there are all those Chinese students and academics in UK universities, accounting for £2.3bn per year in fees, according to the Higher Education Policy Institute. Many of Britain’s universities would go bust if Chinese students stayed at home. And many technology and engineering departments would go intellectually bust if their Chinese faculty and research centres were evicted.

The cases of BYD and UK academia highlight how successful UK-China engagement could be. China is our fifth-largest trading partner. We import more goods from China by value than from the US, and Xi’s Beijing has been a good deal more stable and predictable in its trade policies than Trump’s Washington.

But the same Xi regime has been classified by the National Cyber Security Council as a “highly sophisticated and capable threat” in cyberspace. The intelligence services, including MI5, warn of extensive Chinese espionage efforts targeting sensitive UK technology and intellectual property. A 2023 parliamentary report found that China had penetrated “every sector” of the UK's economy.

Then there is Xi the ally of Putin; Xi the threat to Taiwan; and Xi the oppressor of democracy in Hong Kong and throughout China’s territories and spheres of colonial influence.

Put all this together and you have a relationship that needs intensive management, including of threats. Yes, there could be huge gains for the UK from successful partnership, but huge losses will be incurred through complacency and misjudgement.

Indeed, accurately describing the relationship makes a nonsense of simplistic notions of China being an “enemy” or a “friend”. It is both a partner and a threat, and the UK needs to strengthen the partnership while containing the risks. The situation is in some ways akin to Britain’s wary, intense relationship with industrially and imperially surging Germany in the late 19th century. That story ended very badly, but it need not have done so if Britain—and of course Germany—had been better led.

By contrast, Putin’s Russia is very clearly an enemy. There is virtually nothing positive in the relationship. There are only colossal threats from Russia’s invasion of the territory of a fellow European democracy, and Putin’s systematic efforts to undermine not only Ukraine but all neighbouring European states and European democracy at large. The recent story of Reform UK’s leader in Wales, Nathan Gill, pleading guilty to eight counts of bribery in relation to favourable statements he made about Russia are but one example. There is no trade or intellectual relationship of any meaningful kind, either. It is, in fact, a state of war, just short of direct military confrontation.

Any bilateral relationship is complicated, as evidenced by the UK's ties with Moscow and Beijing. Sometimes what's called for is nuance. But at other times what's called for is forthrightness, and the ability to see threats for what they are.