There’s no telling what will make a nonfiction bestseller. Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time and the late Erich von Däniken’s junk archaeology about “ancient astronauts” both seem implausible candidates for sales in the millions, yet attained them. Perhaps even less likely a commercial blockbuster is a book of more than 700 pages, with close type and double columns, about English grammar and words.

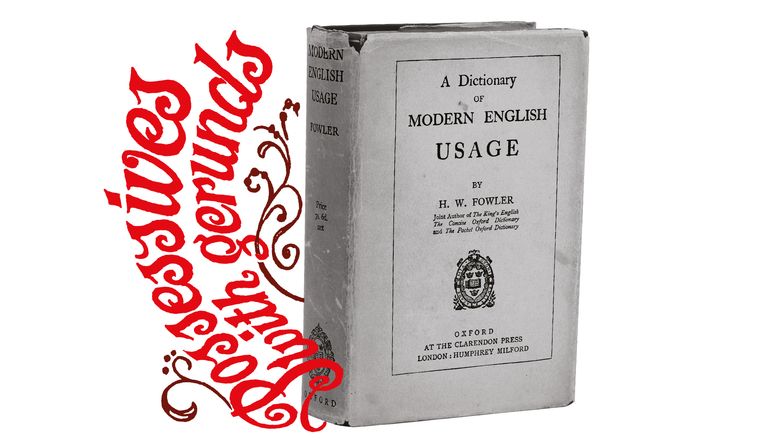

This is A Dictionary of Modern English Usage by Henry Watson Fowler. Published on 22nd April 1926 and selling 60,000 copies in its first year, it swiftly became not just a revered reference work but an institution, known to devotees simply as “Fowler”. Introducing a reissue of the first edition in 2010, the linguist David Crystal wrote: “No book had more influence on twentieth-century attitudes to the English language in Britain.”

The centenary is an apt moment to review the book’s merits and reputation, and to advance a modestly revisionist case. There is much to admire in Fowler. He was a stylish writer who knew grammar. He has a notable place in modern British social and cultural history. He is not and never was an oracle on language and its use, however—and he shouldn’t be treated as such. After 100 years, it’s time to close the book on Fowler.

Many of Fowler’s pronouncements were eccentric and misguided, and have been perversely kept alive by popular usage manuals. He worked independently of modern linguistic scholarship and there is often no basis to his judgements other than personal taste. Further editions of Fowler (the fourth, edited by Jeremy Butterfield, appeared in 2015) replicate his flaws, introduce new ones or give sound advice while going to tortuous lengths to link it to the man himself.

Fowler was born in 1858 and enjoyed a privileged education at Rugby School and Balliol College, Oxford. Early promise was not fulfilled, however. He left Oxford with a second-class degree and a muted character reference, enough to secure a job as a schoolteacher in classics and English. He taught (after a brief spell at Fettes College in Edinburgh) for 17 years at Sedbergh School in Yorkshire. He left on a point of principle, being unable in conscience to prepare pupils for confirmation in the Church of England.

Thereafter, Fowler made a living as a freelance writer, on top of an annuity from his father’s estate. His chance came when he collaborated with his brother, Francis, on a series of classical translations published by the Clarendon Press, an imprint of Oxford University Press. The brothers Fowler, fascinated by what they regarded as solecisms of English usage, wrote The King’s English (1906) and compiled the Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English (1911). These proved popular.

Despite being well over recruitment age, the brothers enlisted in the First World War as part of the British Expeditionary Force in France. To their chagrin, their duties were menial rather than military, and they returned to England after a year. Francis died in 1918 of tuberculosis, contracted during wartime service. Henry continued alone with the linguistic enterprise they’d embarked upon, which came to fruition in the famous dictionary. Movingly, the dedication is to the memory of Francis, “who shared with me the planning of this book, but did not live to share the writing… He had a nimbler wit, a better sense of proportion, and a more open mind than his twelve-year older partner.”

The book is pedagogical, offering instruction and correction. That’s a weighty reason, though far from the sole one, for its success. Many people, out of diffidence and genuine curiosity, seek guidance on their use of language. Fowler met that demand.

In The King’s English, the brothers set out at length the principles of how to write, and more specifically how not to write. It was, as they described it in a letter to their publisher, “a sort of composition manual… for journalists and amateur writers”. In word choice, they urged the merits of being “direct, simple, brief, vigorous and lucid”. Their approach to syntax was to set out a series of alleged solecisms from newspaper articles, with their own corrections. Some of these, such as errors of subject-verb agreement (for instance: “An immense amount of confusion and indifference prevail in these days”, from the Daily Telegraph), were surely due merely to tight newspaper deadlines.

If The King’s English was the preliminary sketch, the Dictionary of Modern English Usage was the completed canvas, its alphabetised entries ranging from the indefinite article “a” to “zeugma”. Fowler is firmly prescriptivist and sometimes unyielding. Take his entry on “unique”, a word often termed by sticklers an absolute adjective, namely one that isn’t gradable. Fowler is with them. He insists that “uniqueness is a matter of yes or no only; no unique thing is more or less unique than another unique thing…”. Hence, according to Fowler, it is illiterate to use the term as a synonym for exceptional or rare, and “it is nonsense to call anything more, most, very, somewhat, rather, or comparatively unique”.

So much for Charlotte Brontë, who in Villette gives to her narrator, Lucy Snowe, the words: “‘A very unique child,’ thought I, as I viewed her sleeping countenance by the fitful moonlight…”

This happens a lot in Fowler’s treatment of words individually and in combination. He proffers apparently authoritative judgements with neither argument nor evidence, while terming alternative usage illiterate. On occasion, he even invents a supposedly crucial distinction out of whole cloth. Witness his claim that a differentiation has developed, and “is now complete”, between “masterful” (meaning imperious or commanding or strong-willed) and “masterly” (skilful or expert or practised). Fowler has made this up, however. Evidently believing that such a distinction ought to exist, he falsely asserts that it does. As the Oxford English Dictionary discreetly observes in its own entry on “masterful”, the word’s use in the sense of skilful “has been criticized in usage guides, apparently starting with H. W. Fowler”.

From Fowler, and him alone, this piece of disinformation insinuated itself into the genre of usage manuals. I cite, almost at random, Grammar and Style (1993) by the philosopher Michael Dummett: “Masterful, which means ‘dominating’, is often used erroneously for masterly, in the sense of ‘worthy of the master of a skill’.”

Yet here we come to an oddity. Elsewhere in Fowler, especially in the mini-essays that punctuate his text, his analysis is often subtle and sensitive rather than censorious. He is good at identifying what makes some writing stilted and artificial. His critique of “elegant variation” (a felicitous term of his own devising, denoting the use of jarring synonyms in order to introduce variety) is acute and still highly relevant. A genuine example I recall is a Le Monde journalist’s reference to “fermented grape juice” for fear of repeating “wine”. (Yes, this was in French, but the point still applies.)

Fowler is justly scathing about what he terms fetishes—namely “current literary rules [that are] widely misapplied or unduly revered”. Among these are the notions that it is wrong to split an infinitive, end a sentence with a preposition or use “different to” rather than “different from”. And, in contrast to the general tenor of prescriptivist writers, he observes (in his entry on “that” as a relative pronoun): “What grammarians say should be has perhaps less influence on what shall be than even the more modest of them realize; usage evolves itself little disturbed by their likes and dislikes.”

Here Fowler expresses an essential truth. It’s not just that language changes (though of course it does); rather, what is “correct” is an empirical question. It doesn’t matter if you dislike the use of “disinterested” to mean bored rather than impartial, or whether you insist on “try to” rather than “try and” or deplore the prepositional phrase (used by Shakespeare among many others) “between you and I”. These usages are so common that they can’t be regarded as errors: they are part of the lexis and grammar of present-day Standard English.

This doesn’t mean grammar lacks rules or that lexicography lacks definitions. Moreover, it’s always open to us to try and change usage. A benign example of conscious linguistic reform is the way that ineradicably sexist terms, such as “he” as a supposedly generic (or epicene) pronoun, have largely disappeared in edited prose over just a generation or two. But it’s a matter of fact, not opinion, whether a construction is grammatical or a definition is accurate. These facts may sometimes have fuzzy boundaries, but they are derived from observed regularities of usage, not the edicts of style gurus.

The besetting flaw of Fowler is that he enunciates the principle of the custom of usage while frequently ignoring it in practice. As Crystal writes in the 2010 edition: “The problem in reading Fowler is that one never knows which way he is going to vote. Is he going to allow a usage because it is widespread, or is he going to condemn it for the same reason?”

This isn’t a problem only for modern readers. Contemporaries too were misled by grammatical analyses in Fowler that don’t hold up. In an entry on “like”, for instance, Fowler quotes Charles Darwin: “Unfortunately few have observed like you have done.” Then Fowler immediately remarks: “Every illiterate person uses this construction daily; it is the established way of putting the thing among all who have not been taught to avoid it…”

So Fowler acknowledges that this construction, which he terms a “conjunctional use”, is part of English usage and that people avoid it only if they’ve been instructed to; and then he condemns it anyway. In reality, modern scholars of syntax would treat “like” in this construction as a preposition taking a tensed subordinate clause as complement; it’s informal, but there’s nothing grammatically wrong with it. A famous example was a tobacco advertising slogan of the 1960s: “Winston tastes good like a cigarette should.” Grammar pedants insisted it should be “… as a cigarette should”. A guide to English that condemns the usage of a great mass of native speakers as illiterate is not going to be accurate.

It’s perfectly reasonable to dislike some usages and constructions, but they are still part of the language

Perhaps the weirdest of all Fowler’s caprices is his objection to what he terms “fused participles”. This means that he regards a clause like “women having the vote reduces men’s political power” as ungrammatical. (The example is Fowler’s own, reflecting both the politics of a bygone era when universal female suffrage had yet to be achieved, and an instinctive misogyny that sadly crops up elsewhere in the book.) And his denunciation of this linguistic “corruption” is extreme. He insists that, to be grammatical, it must be “women’s having…”.

In English we have a lot of words that end in -ing, which can be used in various ways. I lack space to go into Fowler’s case here, but essentially he’s distinguishing between a gerund and a present participle. This distinction exists in Latin but not in English, where you can mark the subject either for plain case (“women having…”) or genitive case (“women’s having”). Both are grammatical, though the genitive is a bit more formal.

You could happily ignore Fowler’s specious reasoning on “possessives with gerunds” but for its adoption by many usage guides since, including the style guide of the New York Times. This is bizarre, because if you adhere consistently to Fowler’s rule you’re bound to end up writing execrable English. Genuine examples he gives of supposed correctness include “will result in many’s having to go into lodgings” or “to deny the possibility of anything’s happening”. According to Fowler, these absurd circumlocutions are mandatory if you’re to avoid the (purely imaginary) error he’s identified.

There is nothing wrong in principle with linguistic prescriptivism. As Randolph Quirk, a pioneering scholar of English language at University College London, noted in the 1980s: “What is certain is that very many people indeed feel uneasy about their own usage and the usage around them. University professors of English receive a steady stream of serious inquiries on these matters from people in all walks of life… These are real issues for real people. And rightly so.”

There are a handful of excellent books that will provide serious answers to these enquiries. My picks would be The Sense of Style by Steven Pinker; Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace by Joseph M Williams and Joseph Bizup; and Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage. The crucial advantage for these authors is that they know the facts of English grammar and lexicography, and ensure their guidance is consistent with these. Few other style manuals consistently meet this prerequisite of usefulness, and Fowler is not among them.

Fowler was lightly revised by Ernest Gowers for a second edition published in 1965. Gowers was a civil servant and author of The Complete Plain Words (1954), a celebrated work on writing clear prose. He did a good job of stripping away stuff in Fowler that was outdated and prolix while retaining the essence and ethos of the book. His edition was well received by Fowler’s admirers; a third edition, edited by Robert Burchfield and published in 1996, was by contrast widely excoriated. Burchfield, formerly chief editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, had in effect written a new book while retaining the talismanic name of Fowler. It had opinions on usage but was far more of a descriptive work than the original Fowler or Gowers’s revision.

You’d have thought readers would welcome a dispassionate account of the state of the language. But that won’t work with the particular constituency that, from my experience, is most likely to read commentaries on English usage. These are people who hold strong views on the “incorrectness” of certain constructions and wish to find them confirmed. Burchfield rarely offered that, however, and was in that respect more attuned to the way scholarly linguists work.

Even so, the third edition of Fowler is unsatisfactory. Burchfield was a lexicographer whose technical knowledge of grammar—there’s no polite way of saying this—wasn’t up to the job. An example is his long entry on the benighted controversy over prepositions ending a sentence. Burchfield correctly says it’s a myth that a preposition at the end of a sentence (a sentence-terminal preposition) is ungrammatical, yet he bungles the analysis. The construction at issue is what’s called a “stranded preposition”. A preposition is said to be stranded if it doesn’t immediately precede its complement. Not all stranded prepositions come at the end of a clause or sentence (“who were you out with last night?”) and not all sentence-terminal prepositions are stranded (“this bed hasn’t been slept in”).

Both these types of construction are grammatical in English, but they differ. In the second example I’ve given, traditional grammars would classify “in” not as a preposition but as an adverb, precisely because it lacks a complement. That analysis is mistaken—it’s still a preposition—but the relevant point is that the spurious objection to stranded prepositions has never been levelled at such constructions. Not understanding that the distinction is crucial, Burchfield cites this second type of construction anyway among his examples of prepositions at the end of a sentence, even though no one has ever claimed it is incorrect. Here’s one, which Burchfield has taken from the Times Educational Supplement: “They must be entirely reliable and convinced of the commitment they are taking on.”

Thus Burchfield’s third edition of Fowler, well-intentioned but blundering, limped on till it was superseded by Butterfield’s fourth. This volume (marketed as “Fowler’s for the 21st century”) is a better book: a serviceable and informative guide to usage. Butterfield is notably more permissive than Burchfield on such disputes as “disinterested” being used to mean uninterested and “anticipate” for expect. But Fowler, this is not; and there should be no titular fifth edition. That’s not a criticism of Fowler the historical figure. It’s rather a plea that publishers and pundits cease invoking the name of a guru whose knowledge was extensive, yet whose advice was of highly variable quality.

For the moment, Fowler’s reputation seems secure. Simon Heffer, the historian and Conservative peer, expressed a common judgement when writing some years ago of the Fowler brothers’ work: “Those who wished to aspire to the highest levels of English bought these books and learned from them. Those who did not continued in their acts of verbal butchery, usually unaware, and certainly unabashed.” This undoubtedly encapsulates the philosophy of Fowlerism. Heffer applauds it; I think it corrosive.

The way native speakers use their own language is a body of evidence comprising a vast corpus of complex syntactic regularities and semantic consistencies. It’s perfectly reasonable to dislike some usages and constructions, but they are still part of the language: they’re not instances of butchery, philistinism or even mere decline. Writerly advice may be valuable to the extent it recognises, rather than stigmatises, these facts of language. And the body of facts will change over the course of a century. For all his insight, flexibility and sensitivity, Fowler made the irremediable error of identifying correct English usage precisely with the way he himself spoke and wrote.