At the end of August, Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds released their 18th studio album, Wild God. It’s a triumphant record, one that grapples with the deep sorrow of the past nine years—in which two of the singer’s sons died, along with his former partner and collaborator Anita Lane—and emerges with something we might call an incandescence. “There’s no fucking around with this record,” Cave has said. “When it hits, it hits. It lifts you. It moves you.”

For a time, Wild God was almost titled Joy. Cave weighed the word carefully and set it aside, concerned that it might be interpreted as “happy”. “Which felt misleading,” he said. But a track named “Joy” still stands on the record—a six-minute composition that arrives four songs in and serves as something like a gyre for the album’s spirit.

Flaming out in synthesiser, piano, French horn, it’s a peculiar and wonderful song; not a rock song exactly, but something more akin to the experimentalism of recent albums Push the Sky Away, Ghosteen and Carnage. “I woke up this morning with the blues all around my head,” it begins. “I woke up this morning with the blues all around my head/I felt like someone in my family was dead.”

This is a familiar lyric for many blues fans. I first heard a version of it in a Bo Weavil Jackson song from 1926 named “You Can’t Keep No Brown”—“I woke up this morning with the blues all around my bed.” But it’s there too in a Blind Lemon Jefferson song from earlier that same year called “Long Lonesome Blues”. And in Louise Johnson’s “All Night Long Blues”, recorded in Grafton, Wisconsin, four years later. The first recorded instance of this line was in “Trixie Blues”, set down in 1923 by Anna Jones and Fats Waller, and in the years that followed it was variously incorporated into blues tracks by Ishman Bracey, Wiley Barner, Sleepy John Estes, Frank Stokes, Vol Stevens and Son House.

It’s not the only blues callback in “Joy”. “I jumped up like a rabbit and fell down to my knees,” begins the next verse. “I jumped up like a rabbit and fell down to my knees/Called out all around me, said ‘Have mercy on me, please.’” Here, Cave abuts another 1926 tune by Blind Lemon Jefferson named “Rabbit-Foot Blues”: “Blues jumped a rabbit, and he ran a solid mile…” against Robert Johnson’s legendary “Crossroad Blues”: “Went down to the crossroad, fell down on my knees/Went down to the crossroad, fell down on my knees/Asked the Lord above, ‘Have mercy, now, save poor Bob if you please.’”

There is something quite masterful in this echoing of blues passim. It announces the song’s sorrowful lineage, a new take on the age-old ache. But it offers, too, a portrait of the catharsis such music can bring.

In Cave’s song, an after-midnight visitation of a “wild ghost”—a “flaming boy”—heralds an end to the anguish. “We have all had too much sorrow,” he tells the singer. “Now is the time for joy.”

The song opens out then. Looks across the wide world to see people shouting “their angry words about the end of love”. And then it looks up to the night sky and sees in the stars some great riposte to such fatalism and rage. There they stand, he says, like “Bright triumphant metaphors of love”.

Twenty-five years ago this month, Cave gave a lecture at the Atelierhaus der Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Vienna, on the nature and composition of the love song. He was 40 then, and looking back over the 20 years of his career, the singer spoke of how it was the early and traumatic death of his father that had led him to songwriting. Words were an attempt to fill the void. “I found through the use of language, that I wrote God into existence,” he said. “Language became a salve to longing.”

Cave found his language came to rest most deeply in the love song. At that point, he wagered he had written some 200 songs, the bulk of which were love songs. “The love song is the sound of our endeavours to become God-like,” he said, “to rise up and above the earthbound and the mediocre.”

In “Joy”, I hear the sound once again of this exquisite endeavour: from the depths of the blues, the reaching for language, upwards above the earthbound, for those “bright triumphant metaphors of love”. It is a song to fill the void, to find the salve, to bring God into existence once more. It is one of the finest love songs of his career.

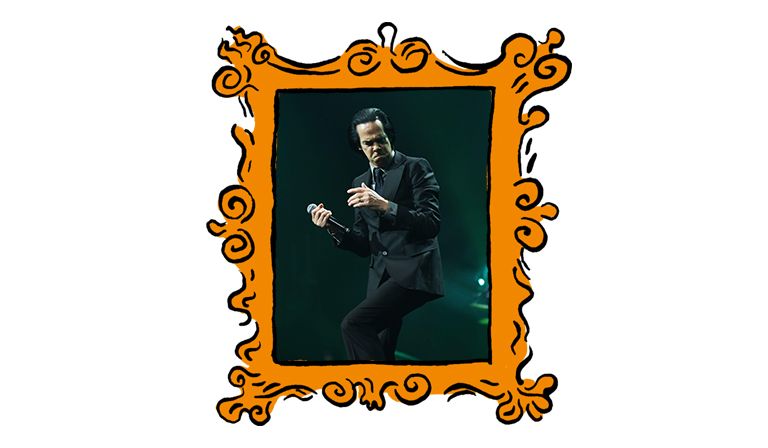

The joy of Nick Cave

Two of the singer’s sons have died in the past nine years. How can—does—he grapple with that?

September 19, 2024

© Capital Pictures / Alamy