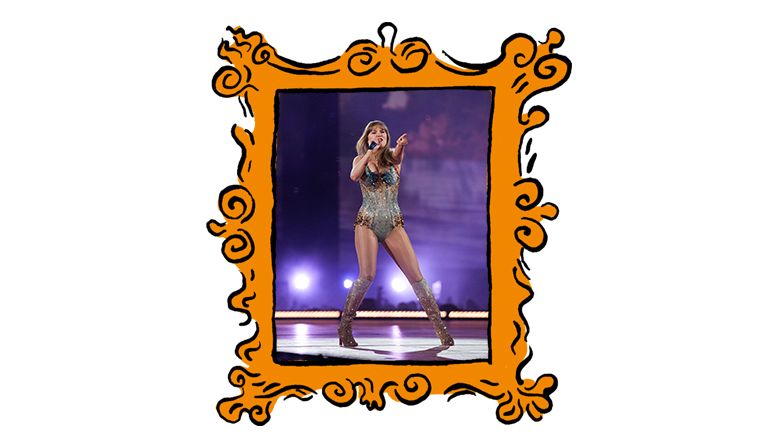

Within one week, exactly seven days and 8,611km apart, I watched two capital-G Great Concert Films: Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense and Taylor Swift’s The Eras Tour.

Going into both of these, I dared myself to remain as ignorant as possible. I had wildly different relationships with the artists on the screen and the gigs these films were memorialising: I loved the music of Talking Heads, but had never seen the film; and I had, knowingly, only listened to one Swift song (turns out that was pure self-delusion and I knew quite a few of them, mainly through Swift’s viral domination of TikTok), but was well-acquainted with her as a pop culture figure.

This exercise came out of a desire to experience them as films, not as a fan. This year, cinematically speaking, has been the year of Barbenheimer and the concert film. And, much like Barbenheimer, the concert film has become a global experience, with simultaneous releases around the world tying into tours, reunions and album releases.

Now it’s Beyoncé’s turn. This week sees the global release of Renaissance: A Film by Beyoncé, which documents her global tour of the same name and provides behind-the-scenes insight into her creative direction.

Not all concert films are made equal—I haven’t seen many think pieces about Machine Gun Kelly: Mainstream Sellout Live From Cleveland, which also came out this year. Nor are they new: much like recorded plays and opera, they have been a lucrative mainstream of cinemas for years already.

But rarely have they been a topic of wider conversation as much as they have this year, perhaps prompted by the coalescence of the worldwide tours of two pop stars of cultural enormity (Taylor Swift and Beyoncé, not MGK) and the transfiguration of those expensive, not always accessible experiences into a form that suggests intimate proximity to the revered stars.

Usually, concert films will simply be a refashioned, remastered or otherwise re-released iconic performance, such as David Bowie’s last Ziggy Stardust show at the Hammersmith Odeon in 1973 or Maria Callas’s one-night-only performance at the Paris Gala in 1958. Sometimes they are gimmicky sets by a once-legendary band trying to cash-in on nostalgia (This April, Billy Idol recorded a gig he played at the Hoover Dam for just 250 people).

Alongside music docs, which have become a staple for both established and up-and-coming performers (from Lady Gaga to Lewis Capaldi and Robbie Williams), concert films of all kinds are designed primarily to super-serve a loyal audience. They sit, as a genre, somewhere between marketing and advertising. It would be naive to say that Swift, Beyoncé or even the Talking Heads did not consider a concert film as a revenue stream as well as an artistic endeavour.

The most memorable concert films, though, use the medium of film to encase in amber a highly controlled performance, making choreography look effortless and improvised even when it is far from either of those things. The creative control that both Swift and Beyoncé exert over every atom of their work and public image, as well as their clear interests in the moving image, make their films something bigger and bolder. Beyoncé has already given us the pioneering, astonishing visual albums Lemonade and Black Is King, while her 2019 film Homecoming looked at the formation of her Coachella headline performance. Renaissance blends both approaches, showing the woman behind the icon while never letting us forget her artistry, her image, the spectacle that is Beyoncé.

Swift too has dabbled in filmmaking, directing the extended video for “All Too Well” as well as several of her music videos. (She is also slated to make her feature length debut at some point in the near future.) While she hasn’t directed The Eras Tour—that’s been handled by Sam Wrench, who has made a career directing concert films for the likes of Billie Eilish, BTS, Lizzo and Blur—all the swooshing cameras and drone shots never let you forget just how undeniable Taylor Swift’s mass appeal is. Meanwhile Jonathan Demme, the director of Stop Making Sense, remains a master of any and every genre. Shot 40 years ago across four performances by the Talking Heads, his film unfolds itself slowly, starting with one person (who else but David Byrne with a cassette player and a guitar) and culminating in a heaving, drenched group of musicians. We barely glance at the audience, so exhilarating and engrossing it is to see the musicianship built up in this way.

Yet watching these films in the cinema, surrounded by knee-bobbing hipsters for Stop Making Sense and by singing girls for The Eras Tour, I realise the music is not the point at all. Nor is it the spectacle or even the direction. It’s the access. The proximity. The largesse that only the cinema can grant. The ultra-front-row access to an artist at their peak. The possibility of seeing David Byrne, Taylor Swift and Beyoncé sweat in 4K. (Joke’s on me: Beyoncé doesn’t sweat.) Through film, the concert becomes a megaton experience for those of us who were not alive for (or could not afford) the live gig.