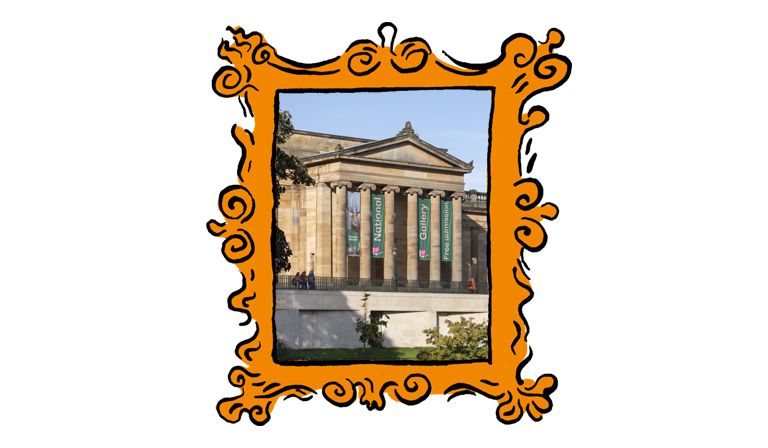

If you head into the Scottish National Gallery from its newly renovated entrance looking out over Princes Street Gardens in Edinburgh, you’ll doubtless be struck by one thing: the light. This is no longer the dark and dingy underpass it was formerly, when it was more often treated as the way out of the gallery—literally, an exit via the gift shop—than an inviting way in.

It is from here that the new and improved galleries are reached; recently reopened after the usual story of lengthy delay and mounting costs, and not only giving space to works sequestered in storage but also connecting the National with its sister institution, the Royal Scottish Academy. The implication of cohesion and unity is obvious. It is here, the new National says, where all Scottish art comes together.

Swing to your left as you come in and you’ll find a long strip of rooms charting over a century of Scottish art from the 20th century backwards, with paintings and sculptures punctuated by views of the gardens from floor-to-ceiling windows. Beginning with Anne Redpath’s The Indian Rug (or Red Slippers) from 1942, you’ll go via the likes of William McTaggart, the Glasgow Boys, Phoebe Anna Traquir and Hill & Adamson, before culminating in Edwin Landseer’s The Monarch of the Glen from 1851. A staircase next to the Landseer takes you up and back to the old galleries, with their more traditional dark-painted walls and familiar pan-European fare.

Many of the works in the new space are not new themselves; in fact, some will be immediately recognisable even to those who have never set foot in the gallery, the Landseer included. Yet it’s hard to deny that seeing them displayed so differently injects them with renewed vitality. I remember my visits here as a teenager, making my way from the lofty upstairs room that displayed Paul Gauguin’s Vision of the Sermon, going down a level, and then another, and another… until you reached the Scottish art section, practically hidden away in the basement as if it were either an afterthought or an embarrassment, or both. It’s a bold statement of intent from the gallery to have this same art at the forefront of its renovation, brash and unignorable, signalling confidence in what Scottish artists have contributed to the country’s cultural imprint.

Yet, the new gallery windows have opened just in time to afford its visitors a very different view of that same culture. Right now, the lawns of Princes Street Gardens are being laid over with metal sheeting in preparation for Edinburgh’s Christmas market. Tacky and overpriced in the way only really cheap things can be, the market is symptomatic of the wholesale commercialisation of the city centre that occurs from August straight through to Hogmanay. The underlying assumptions appear to be that anything worth doing shouldn’t be free and that tradition is a privilege that must be paid for. When the market leaves in January, it will inevitably leave the gardens in a muddied ruin, making the rest of winter even more dreich. The difference in priorities driving the National Gallery and what is going on just outside it could not be further apart.

Which brings to mind a question. The renovation of the gallery was a long and torturous process, yet the inexorable (and encroaching) growth of the Christmas market, year on year, has always been as good as given. If it’s taken us this long to give historical Scottish art the time of day it deserves, what does that say about our attitude to the art being made in the here and now?

In answer to this, I can’t help but think part of the problem lies in a centuries-old tension within Scotland about what the arts are meant to do or achieve. In his tract Aesthetics in Scotland from 1984, the modernist poet and firebrand nationalist Hugh MacDiarmid lamented the longstanding Scottish intellectual tradition that was innately suspicious of the arts in favour of a so-called common-sense philosophy, exemplified by David Hume and the empiricists.

It was this that led, in the modern era, to what MacDiarmid termed “the disassociation of mind from experience”: the assumption that looking at art and the pursuit of “useful” knowledge were mutually exclusive. “With all the facilities at their disposal nowadays most people steer clear of equipping themselves with information about the things they go to see,” he wrote of contemporary gallerygoers. “They do not—or will not—understand that they can only receive from works of art in proportion to what they bring to them.”

Putting aside MacDiarmid’s implicit snobbery for a moment, the relevant point here is that, if art is to mean anything, it requires our active engagement. Without the ecosystem to encourage such engagement, art becomes little more than window dressing—or, worse, elaborate scenery for tourists buying overpriced hotdogs from a faux-German hut.

Without doubt, the new National Gallery is a welcome corrective, but perhaps what we should really ask is why we needed such a corrective in the first place. The arts in Scotland remain, as they do in much of the UK, in a state of constant existential anxiety. In August, it was announced a third of jobs across museums in Glasgow are to be cut, including at the (also recently reopened and renovated) Burrell Collection; at present, there are only two full-time arts correspondents across the whole of country.

There remains much more to be done before it can be said with confidence—to paraphrase Alasdair Gray—that people in Scotland are living here imaginatively.