The most affecting section of Manhunt, the Royal Court’s recent play about the killer Raoul Moat, takes place in darkness. For 12 minutes, we are blind. Guiding us through this darkness is the voice of PC David Rathband, the man who was robbed of his own sight by Moat and took his own life when both his body and his marriage buckled under the impact. It is the standout section of an otherwise mediocre piece of theatre. It leaves us in no doubt about the catastrophic impact of Moat’s violence.

Clearly, former chief constable Sue Sim had not seen Manhunt when she sounded the alarm in the pages of The Times (£). Sim was in charge of Northumbria Police during the seven fearful days when Moat terrorised the North East in 2010, targeting police officers and the family of his former partner Samantha Stobbart. Sim, correctly noting that “there is a group of people in society who have wanted to idolise Moat”, leapt to the assumption that Robert Icke’s new play would take the same tack, condemning the “appalling” prospect of a theatre minimising the trauma haunting Moat’s victims and drawing audiences in with an offer of “mere titillation” and “public entertainment”. “My concern is that people will want to go and see a play about a cold-blooded murderer,” she concluded. Let’s hope no one tells her about Macbeth.

If Sim was imagining a bombastic musical about an outlaw’s brush with the law—Bonnie and Clyde featuring Paul Gascoigne—she couldn’t have been more wrong. London’s Royal Court Theatre is hardly the centre of populist mass entertainment: for 70 years, since the foundation of the English Stage Company, it has served up earnest, lefty deconstructions of thorny social issues. Manhunt is more of the same: gritty, high-minded and as fun as a hairshirt. Director Icke, who devised the play with his company and with the input of the journalist Andrew Hankinson, is interested in the causes of male violence. He is clear-eyed about its destructive impact.

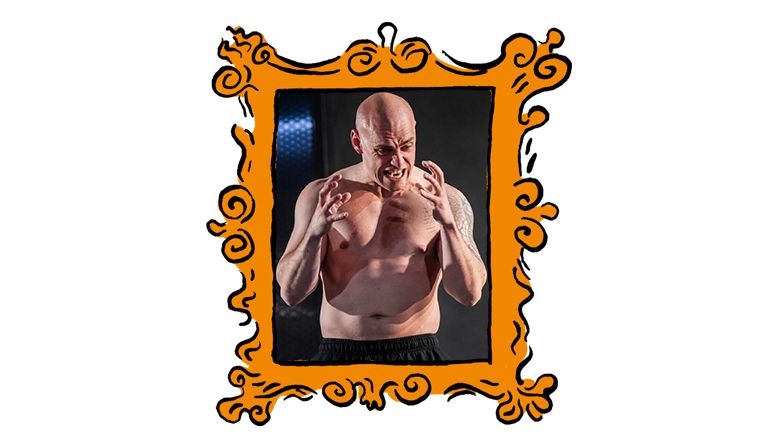

Yet while it’s easy to dismiss Sim’s intervention as ignorant pearl-clutching, I found myself wondering what more thoughtful criticism this woman—who once accused her own force of being an “boys’ club”—might have offered if she had actually seen the play. She was clearly wrong to suggest that Manhunt would glamorise Moat or ignore the suffering of his victims. No one could watch Samuel Edward-Cook’s rage-filled, emotionally incontinent rendering of Moat and walk out wanting to emulate him. The blackout section is a 12-minute exercise in empathy with one victim: Rathband, whose blindness we are invited to experience. But even as Icke explains Moat’s pain and foregrounds Rathband’s voice, he offers no glimpse of the interior life of Stobbart. Whether victim or perpetrator, Manhunt is interested in men, not women.

Icke frames his play as Moat’s story, told in the first section through a series of interactions with social workers, lawyers and judges. Moat is a flagrantly unreliable narrator—yet, for that long opening stretch, Icke never juxtaposes Moat’s self-pitying justifications with anyone else’s accurate version of events.

We hear of Moat’s rage against Stobbart when she dumps him, but we never hear these truths: that he groomed her when he was 31 and she 16; that she told friends she only felt safe enough to exit the relationship once he was locked away in jail; that she told him her new partner was a police officer in the hope it might keep him away from her house (instead, it inflamed him and encouraged his existing grudge against the police). When Moat arrives covertly at Stobbart’s house, both he and the audience hear the women of the house belittling his manhood: a claim the real-life Moat made to justify his actions, and which the survivors deny. He admits to the murder of Chris Brown, Stobbart’s partner, but repeatedly tells us he never meant to seriously harm Stobbart, despite shooting her in the abdomen.

This alone might be forgivable, given that we do clearly see Moat’s violence towards Stobbart. We are here to understand his perspective, after all. Yet where his mind is brought to life in 3D, women are uniformly flattened into 2D. All but one of the social workers, lawyers and judges who hound Moat through the criminal justice system are officious women. Moat explodes in misogynistic rage at each of them: “Shall I punch you five times and see what happens?” There is no suggestion that any of us would like to be locked in an interview room with him. But thanks to Icke’s nagging, pompous direction of each of these female jobsworths, we are left with the insistent suggestion they might deserve it. Social services, by this reckoning, comprise a bloodless, manipulative and thus female system: incapable of speaking to male rage.

None of this should justify Sim’s unsophisticated critique of a show she hadn’t seen. The reverse is true: the Times’s story shows all the hallmarks of a journalist ringing up a public official to provoke a comment and stretch it into a story, which speaks to the vacuous quality of most theatre coverage by news reporters rather than specialists. Instead, the headlines about what a former police officer in Northumbria may or may not think about a play in London have distracted from a more important conversation we should be having: when does “himpathy”, the excessive desire to understand male perpetrators of violence, distract from empathy with their female victims?

Manhunt has finished its short initial run but was evidently programmed with a view to a West End transfer. Although it began life at the subsidised Royal Court, super-producer Sonia Friedman is listed as a backer, which normally means a commercial run is in the offing. If it makes that move, it will join Dear England and Punch, which I reviewed in last month’s issue of Prospect, as the latest entry in a fashion for real-life stories on stage. Watching Manhunt, I couldn’t help but wish that some of these reportage stories had learned from the better practices of high-quality journalism: balance, fact-checking and a victim’s right to reply.

The real crime of the Raoul Moat play

When does an excessive desire to understand male perpetrators of violence distract from empathy with their female victims?

May 08, 2025