Nothing is ever entirely flat in a Milton Avery painting. There is always some movement, a throb or a flicker in his application of paint that slightly, gently moves the eye and holds us there. Boathouse by the Sea (1959) also has this same human wobble in the paint. I am especially drawn to the banding in the painting, the clear graphic divisions as if it were a homemade flag. It feels like a musical thing, the large dark foundation of black anchoring the painting like bass notes, allowing the lighter and melodic passages to harmonise above them. This painting seems one of Avery’s largest, large enough to allow a viewer a sense of being inside it, an immersive effect that is one of the raisons d’être of the work of his friend Mark Rothko. To me, it’s a masterpiece.

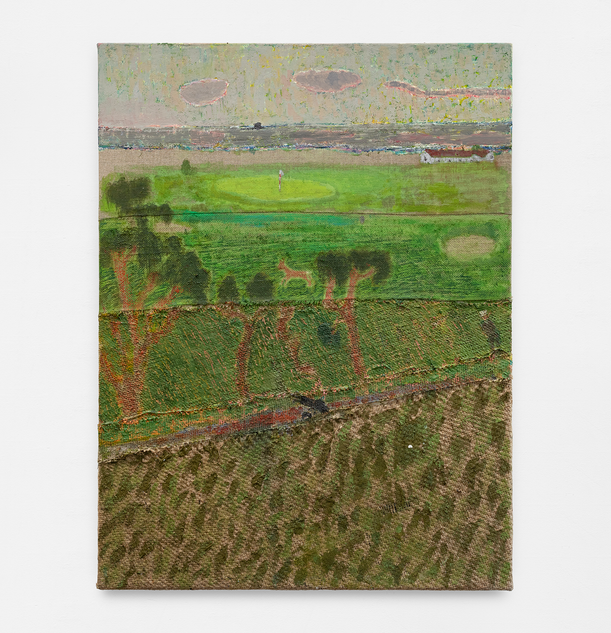

It’s Avery’s musical aspect in particular that influenced the painting I made as a response—Afternoon of a Faun (2025)—where I borrowed the same divisions as Boathouse by the Sea to compartmentalise a landscape, a golf course with its altering of nature into the artificial hierarchy of rough, fairway and green. I got to thinking golf was something Avery could have painted.

I’d heard of Avery long before I ever saw anything by him—which seems all wrong, given how stridently visual an artist he is. It was 25 years ago when the painter Francis Convery asked me, in response to an exhibition I’d had in Edinburgh in 2000—a body of landscape paintings I’d made while travelling around Scandinavia—whether I had been influenced by him. I had never heard of Avery at that point, but after seeking him out in the library—this was early days of the internet—I instantly saw what Convery meant.

I wouldn’t see a painting by Avery for another two decades after that, when I first saw Boathouse by the Sea at the Royal Academy in 2022. It seems unbelievable now that it took so long, but then this was the first time he’d been shown in a solo exhibition anywhere in Europe.

In a strange way, there was initially something about Avery’s work that troubled me, even though Avery is the least troubling of artists. I was troubled by his lightness and simplicity, which—because I was trained in the school of “hard-won” painting—I found hard to accept. I’m so glad not to believe this anymore. It has taken getting older and more experienced to come to the belief that to be simple and good is very hard. (I would say it was Avery who eventually led me to an appreciation of Matisse.) I love the directness of his work, the boldness of it. With Avery, things register firstly as shapes, a beautiful shorthand which almost (but never completely) separates everything from the whole. Though this tendency towards simplicity isn’t constrained by a modernist straight jacket; Avery allows himself diagonals and curves, and humour too. There’s a humaneness in him. Above all, I love Avery’s touch.

As a painter, Avery taught me to “lighten up”, in all senses of that phrase; to see potential in the most ordinary subject matter, to make use of what is around me and see the lyricism of those opportunities; to not show off, to “tell it slant”. I think of him as the painting equivalent of Erik Satie, whose quiet attention is focused on the undramatic, the liminal and in-between spaces, the small things, the unheroic. Like Satie, Avery does not try to make big important statements. And he is all the more radical for it.

Colour Form and Composition: Milton Avery and His Enduring Influence on Contemporary Painting, which includes Andrew Cranston’s Afternoon of a Faun, is on display in Micas, Malta, until 4th April 2026