Who was Aby Warburg? Kenneth Clark, author of Civilisation and one of the few art historians known to the general public, hailed him as “without doubt the most original thinker on art history of our time”. His was quite a life. Born in 1866 into the wealthy Hamburg banking family, he made a deal with his brother to forfeit his right to take over the firm as long as he was always provided with any books he wanted. As keen on archaeology, anthropology and the natural sciences as he was on art, he lived with Hopi Indians in Arizona to learn about their rituals and cosmologies.

During his lifetime, he built up an enormous research collection. Because he was Jewish and it was a shrine to cross-culturalism, this collection was at risk from rising Nazism; so it was relocated to London and now forms the centrepiece of the Warburg Institute in Bloomsbury, called “Britain’s most eccentric and original library” by the New Yorker. Now, almost a century after Warburg’s death in 1929, it’s the inspiration for Black Atlas, an equally original film by Edward George, best known as a member of the Black Audio Film Collective whose The Last Angel of History (1996) is a foundational document of what has become known as Afrofuturism.

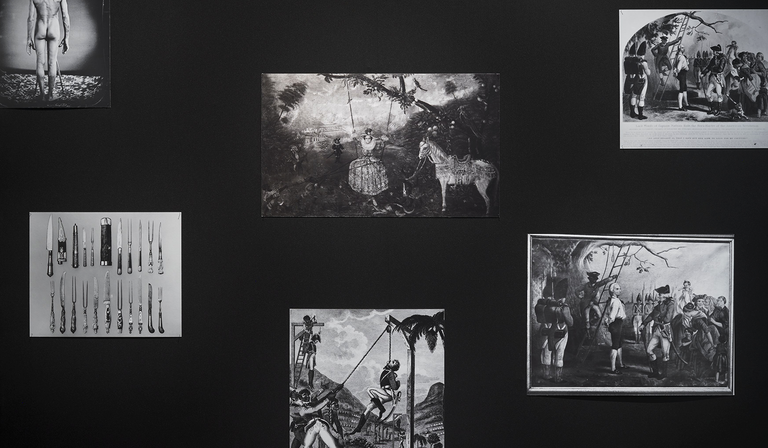

Black Atlas gets its name from Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, a tantalisingly incomplete project in which Warburg assembled many hundreds of photos, diagrams and sketches that he pinned on thematically clustered wooden panels covered with black cloth. He wanted to track what he termed the “aftermath of antiquity”—the ways in which certain images from Alexandrian Greece had reappeared in the Renaissance, the Reformation and beyond. This is art history less as connoisseurship or object analysis as it is about delirium and drift, pattern recognition, following the migration of images across nations, cultures and historical periods. Might they speak an Esperanto of the human soul?

George, too, has been swimming in images—the tens of thousands that make up The Image of the Black in Western Art collection assembled during the Civil Rights era by French-American collectors Dominique and John de Menil. Here, ripped and torn from Africa, scattered across centuries and continents, are black men, women and children—at sea and on shore, shackled and flayed, toiling and dancing, foregrounded and barely perceptible smudges at the edge of a canvas, their faces rendered as furniture details, their mouths crying out. In joy? In rictuses of suffering?

Some images will be familiar. There’s Bosch! Degas! A Hogarth print! Most are harder to pin down. That’s partly because, for so many pieces, the artists as well as the sitters are unknown. They’re often undated too. Even when information exists, George doesn’t divulge it. The closer the camera zooms in, the more ambiguous what it’s showing. Like Warburg, he’s not interested in pinning down these images, in bundling them into schools or genres, in press-ganging them in service of linear arguments. His approach—he calls his film a “poetic image essay”—is more intuitive and associative. It gives viewers room to roam. As an atlas, it’s less a navigational tool than an imaginative cartography.

The Warburg library has a famously idiosyncratic classification system, with sections devoted to topics such as Magic Mirrors, Knots & Mazes, Polemics against Freemasonry. George also has odd—oddly direct—names for some of his image-sections: Monkey, Collar, Sex, Face. The cadenced questions he poses on his voiceover are self-reflexive, sometimes unanswerable, in dialogue with heady thinkers such as Derrida, Lacan and the black American poet Fred Moten. They’re very different from the hectoring simplicities too often peddled by public historians talking about race.

Philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman argued that “Warburg is our haunting; he is to art history that which an unredeemed ghost—a dybbuk—might be to the place where we live”. George, in a similar vein, remarks, “I am surrounded by ghosts of ways of seeing; the work of ghosts and their ways of seeing look back at me. I ask myself: whose ghosts are these, and in whose bodies do these ways of seeing now haunt the present?”

Ways of Seeing was the name of a landmark television collaboration between Mike Dibb and John Berger that brought the ideas of another German Jew—Walter Benjamin—into the public consciousness. Black Atlas is as rich and thought-provoking as both that and Laura Mulvey’s exploration of the “male gaze” in her now 50-year-old essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”.

Since the early 1980s, when he was stealing photos from National Geographic, George has been recontextualising and reframing images of blackness. He encourages us to linger longer with them, to listen as much as to look at them, to imagine our once and future relationship with them.