The UK’s record on Sudan looked good on paper. Since the war began in 2023, it has sanctioned companies linked to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), provided more than £230m in aid and liberally expressed horror and condemnation at reports of war crimes—a stark contrast to its reaction to the moral failings of Israel. It is the “penholder” for Sudan at the United Nations Security Council, meaning it takes a lead role in drafting and negotiating actions concerning the country. But the UK can no longer turn a blind eye to its indirect role in the conflict.

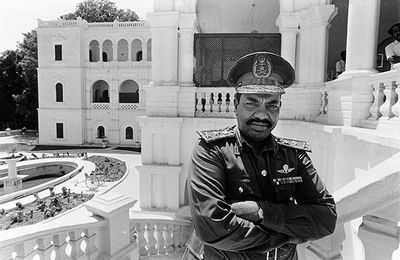

The United Arab Emirates is widely recognised as a primary enabler of horrors perpetrated in Sudan. It has reportedly been bankrolling and effectively backing the actions of the RSF since 2023, supplying powerful weapons and drones, treating injured fighters and influencing media narratives. The UAE has been the primary destination for gold smuggled and exported out of RSF-controlled areas since the start of the war, with production almost doubling between 2022 and 2024, despite the fighting. And it has good relations with General Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo, known colloquially as “Hemedti”, the warlord who leads the RSF. Hemedti has supplied RSF mercenaries to fight on the UAE’s behalf in Libya and Yemen for years; Emirati banks hold RSF money. Cameron Hudson, a former CIA analyst and a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies thinktank told Le Monde that the war would have already concluded had the UAE not so determinedly supplied the RSF with weapons. So determinedly, in fact, that military aid has doubled since April, he said.

The Sudanese government has accused the UAE of complicity in genocide through its arming of Hemedti’s men—and it is on this point that the UK could make a difference. Hemedti also has help from the Russian mercenary group Wagner, Libya and other actors, but while the UK does not have intimate business relations with the Wagner group, it does with the UAE.

The UK has exported more than £1bn of arms to the UAE via standard export licences since 2019, making it one of Britain’s biggest customers. This takes place while the UK openly supports an embargo on all arms to Sudan. The UAE rejects any claims that it gives military support to the RSF —and why would the foreign minister Yvette Cooper want to believe otherwise?

The British government has involved the UAE extensively in diplomatic efforts, and when questioned in the House of Commons, Cooper has mentioned “putting pressure” on the “Quad” —the United States, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt—for a “humanitarian truce”, while saying little in parliament to question why this war is being waged or about the involvement of other states. A diplomatic conference hosted in London this April with the aim of finding a solution unhelpfully excluded both parties directly involved in the conflict, including the Sudanese foreign minister. Indirect negotiations in Washington this October—this time allegedly involving the RSF and Sudanese government—were also thwarted by the UAE, according to Le Monde. Just days later, the RSF massacred an estimated 460 people at a hospital in El-Fasher.

The conflict is getting more difficult for the UK to ignore. Last week, the Guardian reported that British military equipment has been found on battlefields in Sudan. Records of licenses supplied indicate that in September 2024, three months after the Security Council found evidence of the presence of the “ML4” category of small-arms equipment in Sudan, the UK issued an export licence that allows it to send unlimited quantities of the same type of products to the UAE.

On Saturday, Cooper, acknowledging the atrocities in El-Fasher, committed £5m more in aid and criticised Russia for blocking a UN Security Council resolution on humanitarian access a year before. But last Thursday, foreign minister Steven Doughty still declined to comment on future sanctions in Sudan, much less a halting of weapons exports to the UAE. Although Doughty acknowledged that “British-made items” were found in Sudan, he said this was not evidence they were being used.

Meanwhile in Sudan the official death toll has climbed past 40,000, but aid groups suggest it could be much higher. Nearly 9.5m people have been internally displaced, with millions more having fled towards Chad, Libya and the English Channel. Videos emerging from El-Fasher showed massacres in hospitals and execution “killing fields”; satellite images reveal neighbourhoods stained with blood. According to Unicef, children as young as one have been subject to sexual violence, as the RSF runs rampant in Darfur.

Something has shifted: even the UAE admitted for the first time on Sunday that it “made a mistake” by not sanctioning the RSF and army leaders who instigated the 2021 coup that later led to the war. And yet, as gruesome stories leak out of Sudan, it is clear that Britain could use this moment to do more.

For now, 70,000 people have been displaced by the violence at El-Fasher. Tens of thousands are now fleeing to Tawila in North Darfur, making the dangerous 80km journey on foot while facing extreme hunger. With reports that the RSF may be selectively targeting non-Arab tribes for ethnic cleansing, many surely fear that violence will follow them. Unfortunately for them, Britain’s weapons trade with the UAE goes on. Those weapons may well be involved in war crimes. It’s business as usual.