A few months ago, I wrote in these pages about rampant sexual abuse in a French private school. In reporting that piece, I met with adults who came forward to recount childhoods filled with beatings, molestation and rape. Then, when it was revealed that France’s former prime minister had been involved in covering up the scandal, I watched, dismayed, as words like “violence” and “abuse” slowly disappeared from the coverage, only to be replaced with terms such as “political scandal” and “parliamentary inquiry.” When one of the survivors compiled a book filled with dozens of testimonies from survivors, news reports immediately zeroed in on a single one: the former PM’s own daughter, whose abuse at the school was then used as political fodder in the efforts to try and bring down her father.

These events came to my mind last week after the release of Jeffrey Epstein’s “birthday book”. Instead of reckoning with the decades of abuse meticulously catalogued through the book’s 238 pages, the discourse had zeroed in on one cartoonish doodle of a headless, pubescent woman, whose pubic hair looks a lot like Donald Trump’s signature. Suddenly, everyone seemed to have become a forensic handwriting expert, analysing, as Jimmy Kimmel deplorably put it, Donald’s “long D”. What might his alleged contribution mean for his presidential career? One by one, opinion pieces have appeared about the book’s impact on the professional survival of numerous influential men—articles which invariably fail to even mention the word “girl”.

In all the noise about its (in)famous signatories, we lost sight of what the birthday book actually is. It is not a meme or a punchline or a political prop, but an artefact of the misogyny and abuse that very real girls—now women—lived through.

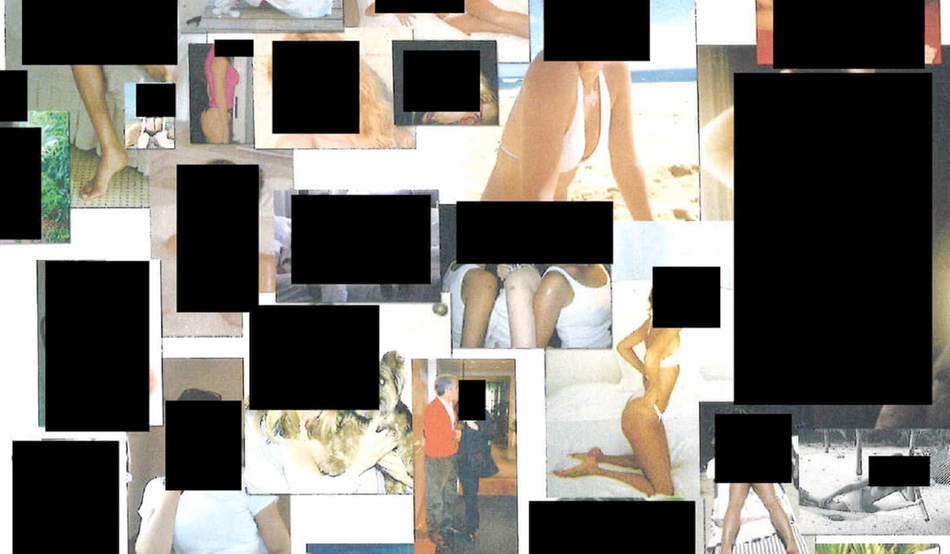

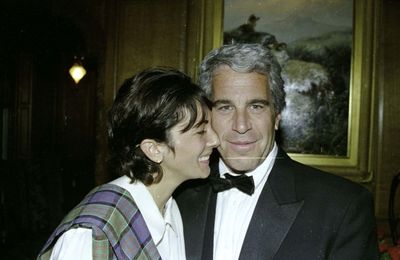

“The First Fifty Years” albums—a set of three tomes curated by Ghislaine Maxwell in 2003 to celebrate the milestone birthday of her onetime lover and fellow convicted child-sex offender, Epstein—read like a frat-boy yearbook replete with sexist in-jokes and ghoulish photographs. Bradley Edwards, the attorney representing Epstein’s victims, said that “it should be set in the Smithsonian as an artefact of this time.” The book is damning, a catalogue of lewd innuendo from the world’s most powerful men, immortalised in leather, as if misogyny were a collectible.

The book must certainly be preserved (and used) as evidence, but we cannot let it become mere spectacle. Every entry we co-opt to bring down a man’s career risks replicating Epstein’s modus operandi: turning women into props while their rich and famous abusers become the story.

As Epstein survivor Wendy Pesante reminded us during last week’s press conference on Capitol Hill: “Being a survivor is not a headline. It’s our life… It’s panic in a grocery store. It’s smiling at work while my hands tremble. It’s waking up at 3am with my heart racing and not knowing why.” Every Trump sketch, every cheque for a “fully depreciated woman” dissected by the media and online commentators, risks overshadowing such victims’ testimonies.

Let’s not forget that, among the girls with no names whose redacted faces flicker through the birthday book, are some of the women who spoke on Capitol Hill, coming together for a press conference for the very first time, amid the House Oversight Committee’s ongoing (and bipartisan) probe into Epstein’s federal crimes. They bravely put themselves in the spotlight to ask for accountability, demanding that the most damning and relevant evidence of their abuse, which remains under lock and key in the Department of Justice’s files, be released: flight logs, financial documents, surveillance tapes. The client list that survivors have begged to see. Instead, these empowered women got a scrapbook filled with pictures of the naked bodies of the trafficked girls they used to be.

As was bound to happen when its pages began circulating online, one of the survivors recognised herself. The “Friends” section of the scrapbook features a hand-coloured drawing of Epstein greeting three very young, balloon-carrying girls within a larger drawing showing a nude Epstein on a sunbed. He is being massaged by four different topless young women while a plane, presumably the infamous “Lolita Express”, as his private jet was known, flies overhead. “When I saw that picture,” explained survivor Jess Michaels on CNN last Tuesday, “all that put me right back there to what happened next.” What happened next—after the massage—was rape. And we knew this long before the drawing began popping up on our newsfeeds. The victims had already told us about all of it.

This is the central cruelty of the birthday book. Yes, it embarrasses its signatories, but most of them have already said they didn’t remember signing it, or that they meant it as a joke, or that the whole thing is a “Democrat hoax”. The ones who the book really harms are Epstein’s victims.

The girls with no names—the ones whose faces are redacted in the files—are the real story. They were real, live teenagers who thought they were meeting a talent scout, who accepted a cash “favour” from a classmate, who boarded a private jet without understanding it was a trap. If we focus on the signatories of the birthday book rather than its victims, it becomes another artefact of erasure, not of accountability.

Survivors are being asked to live through the same cycle again: testimony, dismissal, spectacle, silence. In an interview earlier in September, Jena-Lisa Jones described the exhaustion of being repeatedly forced into the spotlight: “We’ve been having to do interviews like this to get our voices out there because they didn’t just listen the first time we said it.”

Yet again, survivors face triggers and scrutiny only to be drowned out by the whir of partisan scandal, or, in one chillingly literal example, by a military flyover during the survivors’ gathering in Washington last week. Mid-speech, US Air Force jets thundered overhead, drowning out their voices. The official explanation was that it was a tribute to a fallen pilot. But the symbolism was hard to miss: women opening their mouths to tell the truth; the state silencing them with a show of virility. This is the choreography America prefers. Survivors speak, planes fly overhead, cameras pan back to the famous men explaining away their contributions to this gift for Epstein’s birthday, and, more importantly, the maintenance of a culture of systemic abuse.

What should we do with this obscene book? Keep it, yes. Analyse it as a case study in the violence inherent in misogyny-as-humour. Place it next to the Access Hollywood tape in the museum of patriarchal impunity. Just don’t mistake its publication for any form of justice. Don’t confuse gawking at men’s lurid fantasies, at jokes told at the expense of survivors, with listening to those survivors.

“We are not the footnotes in some infamous predator’s tabloid article,” Jess Michaels said in Washington last week. “We are the experts and the subjects of this story.” Another survivor, Haley Robson, made a request: “I would like Donald J Trump and every person in America and around the world to humanise us, to see us for who we are and to hear us for what we have to say.”

The lesson of the birthday book is not that Trump can’t draw, or that Clinton wrote a syrupy note, or that Peter Mandelson was careless enough to leave behind a record of his complicity. The lesson is this: that political theatre is still more compelling to us than listening to women.