Are you ready for war?

I’d like you to pause for a moment and really consider how you’d answer that question. You might begin by breaking it down: what kind of war? Ready to do what, exactly? And is the “you” meant to be you as an individual, or as part of a collective?

Let me suggest the most likely answer: no. You’re not ready for war. Very few people are. Even those whose job it is to prepare for war daily often aren’t truly ready until it begins in earnest. So, while you stay present with that question, let’s consider what an ordinary civilian might need in order to be as ready as possible.

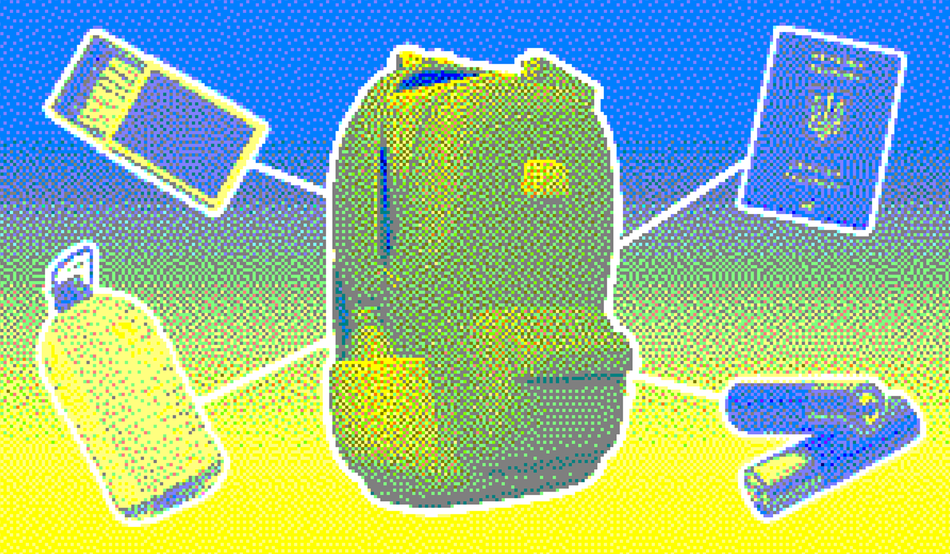

In the days and weeks leading up to the full-scale invasion, Ukrainians were sharing lists of what should go into an emergency bag, known in Ukrainian as a tryvozhna valizka. The word tryvoha in Ukrainian means both “anxiety” and “alert”—povitriana tryvoha, for instance, means “air raid alert”. I like to think of the tryvozhna valizka as a bag that helps us package our anxiety in a way that keeps us alert.

One of the key rules for a successful emergency bag is that you must be able to carry it on your own. In a moment of crisis, if you need to move quickly you can’t afford to be weighed down by your luggage. If you’re fit and well, chances are you’ll end up helping someone else carry theirs. That means only the absolute essentials can be taken with you.

To make the task of packing easier, I’ve grouped the recommended items into five categories: documents, first aid, basic food and water supplies, a survival kit, and money and a list of next of kin.

Now that we’ve worked out what needs to go into the emergency bag, I’d like you to take this mental exercise a little further: what if we consider not just our own survival, but that of our community, our country, our region or maybe even the planet?

If we translate these five categories from physical items into broader concepts, they might look like this: documents, proof of who you are—your passport, for instance—are about identity; your medical kit, for example a tourniquet that can stop bleeding and give you a better chance of surviving injury—that’s about resilience; basic provisions to keep your body alive—those are sustenance; your survival kit, candles, matches, batteries, a paper map to navigate the terrain when GPS signal fails—they are about autonomy; and finally, your cash, bearing in mind that bank cards could be useless if basic systems and order collapse, and a list of key contact numbers (again, mobile reception may well be down)—these things are about security.

A simple rule for packing, which I picked up in my youth as a moderately keen hiker, is to place the heaviest items at the bottom and layer lighter items on top. This reduces the risk of toppling over and giving yourself a concussion before your journey even begins.

So: identity, resilience, sustenance, autonomy, security. What shall we pack first?

I suggest we begin with autonomy. It carries no small amount of weight.

The very notion of keeping an emergency bag is bound up with securing one’s own autonomy. What is autonomy, if not self-reliance? At first glance, that might suggest a clash between the personal and the collective. Sharing the few meagre provisions you’ve managed to secure could rob you of a better chance at survival. However, as Rebecca Solnit writes in her essay “The Ideology of Isolation”, “no one is wholly independent. You can’t survive without taking air into your lungs, you didn’t give birth to or raise yourself, you won’t bury yourself, and in between you won’t produce most of the goods and services you depend on to live. […] we are in it together, for better or worse.” And so, when it comes to gaining and keeping autonomy, and then cultivating from that independence, we are far better off working in concert with others.

What kept Ukraine bound in Russia’s imperial grip was the absence of autonomy: political, economic, cultural. What gave Ukraine the chance to escape that grip was the act of claiming autonomy. And what frightened the imperial centre enough to unleash political violence was the sight of Ukrainians actually practising autonomy.

While individual voices—from poets to politicians—had long called for Ukrainian autonomy, it was the collective that made the independence real. The too often overlooked referendum of 1st December 1991 confirmed Ukraine’s declaration of independence. The turnout was 84 per cent—a level of political engagement most 21st-century politicians can only dream of—and of those who took part, over 90 per cent said yes.

Crucially, this support wasn’t just felt in some parts of Ukraine; it was in all of Ukraine. Even in Crimea more than 54 per cent voted for independence, at a time when the Crimean Tatars—the peninsula’s indigenous people, persecuted and deported by Stalin—had only just begun to return home, had only just begun to imagine reclaiming their autonomy. They imagined it as part of an independent Ukraine. In Donetsk, Luhansk, Odesa, Kharkiv and Kherson, regions that are habitually claimed by Moscow as part of its “Russian world”, and that suffer from heavy Russian bombardment today, between 80 per cent and 90 per cent voted in favour of independence in 1991. In other parts of the country, the figure was between 95 per cent and 98 per cent.

This page of recent history is all too conveniently forgotten by those who question Ukraine’s ability to secure and defend its autonomy. Yet it is unambiguous proof that Ukrainians of every political, ethnic and linguistic stripe were united in one thing: the desire to live in an independent Ukraine. In 1991, that desire found expression in the simple act of picking up a pen. More than three decades later, the same goal compels people to pick up arms.

Autonomy, then, is not about going it alone. It is about being able to lean on others, and letting them lean on you to protect independence, both individual and collective. It is hard-won for many, and it is fragile for all. And when it’s threatened, one must be ready to protect it. Which brings us to the next item for the emergency bag—resilience.

Resilience is not merely about surviving hardship—it is what allows you to stand up after a fall and to keep going. It is forged in the crucible of difficulty, yet we should resist the temptation to romanticise it as something that gives meaning to suffering. Trauma leaves scars on both individuals and societies. Resilience may grow from those scars, but if wounds remain unhealed, they can reopen. True recovery becomes possible only when survival is paired with justice.

Stanislav Aseyev’s account of his time in Izoliatsiia (Isolation)—a Donetsk art gallery that was turned into a concentration camp by Russian proxies in 2014—brings the link between resilience and justice into sharp focus. A writer, journalist and human-rights activist, Aseyev endured inhumane conditions for 962 days. In his book, The Torture Camp on Paradise Street, he recounts the daily torments inflicted on him and his fellow inmates: electrocution, beatings, torture, humiliation. He says that in order to write the book, he had to first survive, “And in order to survive,” says Aseyev, “I had to believe I would write it.” The will to testify fuelled Aseyev’s resilience.

He writes of justice too, and it is hard to tell which passages carry more bitterness: those detailing the suffering, or those acknowledging that the suffering was meted out with complete impunity. “In this account of my time in Isolation,” writes Aseyev, “I purposefully avoid using surnames or even first names. It would be cruel to name a survivor. For anyone who’s been through that place, rape, and torture, recognising themselves in this book would only add to the trauma. As for the perpetrators, they can keep their names until they face justice. I know none of them have repented; every word I write is a joke to them.”

The testimony of a survivor or a witness who can bring evidence of crime into the court of law can help create resilience—but only if it is heard, validated and acted upon by wider society. Collective indifference to one’s suffering, on the other hand, can complete the work of the tormentor. The pursuit of justice, therefore, is essential in strengthening the resilience not only of those who suffered directly but of those around them as well.

So, we’ve now packed two rather bulky items: autonomy, which comes hand in hand with unity, and resilience, which draws its strength from justice. The next thing to consider is sustenance. This needs to be within easy reach in our emergency bags, and we must ensure it doesn’t spoil too quickly, as nourishment can swiftly turn into poison.

If we think of sustenance at the level of a country—Ukraine—we must consider how its place in global food production has been compromised by war. Ukraine, the proverbial breadbasket of Europe, is one of the world’s largest producers of wheat, maize and barley, and until the full-scale Russian invasion, it was the largest exporter of sunflower oil, providing nearly half the global supply. Ukraine’s exports are critical for regions such as the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia. Because of this, even small disruptions in Ukrainian food exports ripple outwards, pushing up global food prices and threatening some of the most vulnerable parts of the world with famine.

As a result of Russia’s invasion, Ukraine has become the most landmined country on earth. Vast swathes are contaminated with mines and unexploded ordnance. Since February 2022, hundreds of civilians—including children—have been killed or maimed because of the mining. Agricultural workers are among the most exposed, as fields across the east and south remain unsafe. Until this land can be cleared, Ukraine’s role as a cornerstone of global food supply will remain uncertain.

To meet this challenge, one of the largest demining operations in history is underway, supported by many countries. Modern technologies—drones, AI mapping, robotic deminers—are being tested to speed up clearance. Yet even with such support, the task could take decades.

And it is not only farmland that has been poisoned. Water supplies, too, have been compromised. Shelling and strikes on industrial sites—factories, refineries, fuel depots—have released toxic chemicals, heavy metals and waste into soil, air and rivers. The destruction of the Kakhovka Dam in June 2023 remains the starkest case of an unfolding ecocide.

The damage is not only immediate. Contaminated soil, unexploded ordnance and polluted waters may blight agriculture for years to come. Ecosystems already strained may never recover without sustained restoration. This cannot be faced by one nation alone. When the consequences of conflict and environmental damage cross borders, our response must do the same—global challenges demand global collaboration that goes beyond national interests.

And this brings me to another item for our emergency bag: identity.

When they say territories, we, Ukrainians, hear homes and ancestral graves. When they speak of rare earth minerals, we think of fellow citizens—like my own brother—who have laid down their lives defending that land

Twentieth-century nationalism brought immense suffering, particularly to national minorities and stateless nations. In this context, expressions of national identity can appear radical, often serving to exclude those deemed not to belong. Yet when national identity is rooted in active citizenship and grounded in mutual protection of everyone’s rights and in political inclusion, it can also foster qualities essential for the survival of communities, such as resilience and autonomy. It is therefore hardly surprising that Russia’s war targets not only Ukraine as a state, but also the very notion of Ukrainian identity. Nowhere is this more evident than in the attempt to erase the national identity of the younger generation.

For more than a decade of Russia’s assault on Ukraine—and especially the last nearly-four years—I have travelled across countries and continents, imploring audiences to care about the largest and bloodiest war on European soil since the Second World War. I have encountered genuine sympathy, but also a great deal of indifference. There are often those eager to tell me what’s best for my country—for instance, that surrendering territories (didn’t they once belong to Russia anyway?) is the price to pay for peace. Like a broken record, I reply that when they say territories, we, Ukrainians, hear homes and ancestral graves. When they speak of rare earth minerals, we think of fellow citizens—like my own brother—who have laid down their lives defending that land, and of those still there whose lives under occupation are reduced to mere existence. To abandon those people would be to condemn them to suffer the crimes that have been meticulously documented in every corner of Ukraine that has been subjected to Russian occupation. Too often, my words are dismissed as those of a traumatised Ukrainian, a grieving sister overcome by emotion.

But there is one truth that always stills the room: the mass abduction of Ukrainian children who are forcibly naturalised, subjected to coerced adoption or fostering, Russified, militarised and stripped of their national identity. No one has yet dared suggest that we ought to let Putin keep our children in exchange for peace. No one has argued that Ukrainian children somehow belong to the Russian nation.

Estimates of the number of Ukrainian children abducted by Russia vary: Ukrainian authorities cite just under 20,000 identified cases, while the Humanitarian Research Lab at Yale has tracked more than 35,000. Everyone involved in tracing these children agrees the true figures are far higher, obscured by Russia’s attempts to cover up the abductions through forced naturalisation and the adoption of Ukrainian children by Russian families. Russia has simplified the procedure for the naturalisation of Ukrainian children as Russian citizens, effectively erasing their true identities.

To dismiss nationalism as no more than a construct is to dismiss these identities that are being attacked and erased. To perceive borders as arbitrary is to ignore the reality of those who endure occupation. In many places, the border between one’s own country and that of the aggressor marks the line between relative safety and total danger.

National identity is shaped by cultural imagination, but it is not imaginary. It is the channel through which people assert their existence against those who would deny it. Nor does it need to exist in opposition to identities that cross national lines. On the contrary, it is by respecting each other’s distinct national identities, and allowing for their complexity, that we can build a shared identity based on values.

And that brings me to the final item that must go into our emergency bag: security.

There are those of us who feel a greater sense of security through membership of wider communities or structures: the EU, Nato, and other military or economic alliances. (Although increasingly, our reliance on these institutions is being tested.) Those of us who were never granted entry to such exclusive clubs have had to seek security elsewhere. For me, one of the most vital sources of security has always been culture.

Rarely does a public talk I participate in go by without someone asking how to save Russia. Russia, not Ukraine. The assumption seems to be that the country of Pushkin, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky must somehow be rescued from the evil that has befallen it. This superficial engagement with Russian culture is insufficient to grasp that seeds of hatred of the Other can be found within its works, but it is apparently enough to inspire readiness for a rescue mission.

Equally, the lack of knowledge about Ukrainian culture—even a superficial understanding—has fostered indifference towards saving Ukrainian cultural heritage, which is being burned in libraries, destroyed in archives and buried under the rubble of bombed out museums, theatres, galleries and concert halls. This ignorance can keep us blind to the fact that more than 240 Ukrainian writers, artists and other creatives have perished in Russia’s war already, and with them, the unrealised works within which our fragmented identities might have found a true home.

One such creative was Victoria Amelina. A novelist and poet, she became a war-crimes investigator after the full-scale invasion because she believed that bearing witness is a form of administering justice and providing security, if not for her generation then at least those who will come after. She died on 1st July 2023, after being injured in a targeted missile strike on a restaurant in Kramatorsk, while she was dining with some writers from Colombia—trying to broaden the knowledge of her culture beyond Ukrainian and even European borders, and thus strengthen its security. Perhaps to honour her legacy, the next time we are tempted to pick up a tome by Pushkin or Dostoevsky, we could read a book by Amelina instead. Maybe we should even put it in our tryvozhna valizka.

And so, our imaginary emergency bag is beginning to look rather full, and I hope by now you feel a little more prepared to face any calamity with it at the ready. If we have packed it wisely, there should still be room for one small item, the one that is often more important than all the rest. The one that can remind us of things which cannot be packed into a suitcase: the smell of home, the view from a familiar window, the sunlight spilling through the curtains first thing in the morning, the laughter in the room next door.