There might not be a more innocuous centre of influence and resistance in the world than this one. Welcome to the suburbs of Leicester, where Eliot Higgins, founder and guiding spirit of the investigative bureau Bellingcat, lives with his wife and two children. The bearded, spectacled 44-year-old commutes most days to a single-room office near the city’s ring road—and from here he has embarrassed palace-dwelling warlords; helped solve mass murders; exposed far-right ghouls and tripped up totalitarian bullies.

Higgins, who has devoted the last dozen years of his life to untangling the long, knotted lines of misinformation that wrap around and constrict 21st-century discourse, thinks of himself and his Bellingcat colleagues as “an open community of amateurs on a collaborative hunt for evidence... an online collective, investigating war crimes and picking apart disinformation, basing our findings on clues that are openly available on the internet.” As such, he can get going on his day’s work while eating breakfast and getting the kids to eat theirs. “As soon as I’m awake I turn on my phone,” Higgins told me, when we spent a September day together in his office. “I go to the bathroom. I brush my teeth. I check if any stuff has come in overnight.”

“Stuff” is a good word for it. The subjects that Bellingcat focuses its investigative energies on are eclectic, counter-intuitive, often important, sometimes odd. One contributor might track questionable troop movements through a conflict zone in the Middle East while another tries to debunk a pernicious western conspiracy theory. Still another contributor might be trying to overthrow an international spy ring, or find somebody’s stolen pet.

That month, Bellingcat had just published a story about grain-smuggling in Crimea, based on images taken from the website planet.com; and a story about an Israeli military action in Jenin in the West Bank that drew from CCTV stills circulating on social media. The October eruption of violence that would plunge the region into a full-blown war–and raise profound questions about online disinformation in global conflicts—was still about a month away. The Jenin story zeroed in on a single incident on a single road, to try to work out how and why at least three people had been killed.

What unifies almost every Bellingcat investigation is an organisational devotion to the open source. To secure a scoop or solve a mystery, the ideal Bellingcat contributor might use a combination of videos from Instagram, satellite images from Google, digital documents dug up through an online archive called the Wayback Machine or weather reports from weather.com—with links included to each source. Tips come from anywhere and everywhere; most full contributors these days are former readers and admirers of the site who have risen up to become paid staff (Higgins calls them Bellingcats). The idea is to encourage the use of readily available, ideally free-to-use online resources, in combination with Bellingcat’s widely read platform, to push back at powerful bullshitters. “Identify, Verify, Amplify” is the organisation’s founding motto.

A browse through the archives of the Bellingcat website, which was formally launched in 2014 and evolved out of Higgins’s personal blog, Brown Moses, is like picking through the aisles of a journalistic curiosity shop. On one shelf, a story about a fake Pentagon employee; on another shelf, an exposé on a neo-Nazi sauna retreat in Finland; on another shelf, an investigation into an assassination squad. As Higgins put it: stuff. One morning in the winter of 2020, the stuff that hit his inbox overnight was incendiary, scary, darkly funny—probably one of the wildest journalistic coups in the history of the profession.

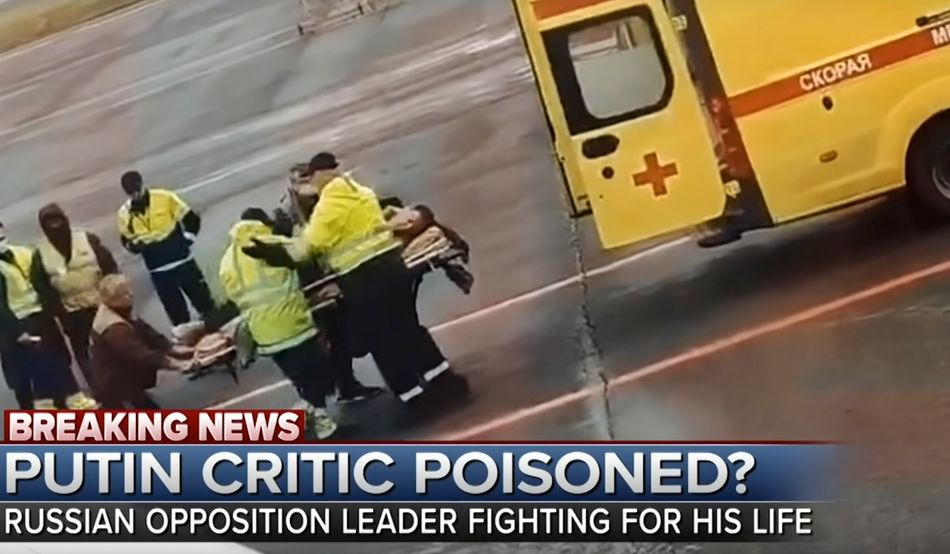

Aided by the painstaking research of Christo Grozev, a Bellingcat contributor, the Russian dissident Alexei Navalny (then in a safe house in Germany) had been able to figure out the identities and telephone numbers of some of the Russian assassins who had only recently tried to murder him. Navalny actually called one of the alleged perpetrators, pretending to be his boss, and teased out a long and detailed confession. They got the entire thing on tape. Miles away in the Midlands, Higgins (rubbing the sleep from his eyes, about to make the kids breakfast) couldn’t believe what he was receiving. “I remember the message from Christo said, ‘Oh, Navalny spoke to the poisoners.’ I thought, ‘What?!’”

That week, working in tandem with other news outlets including CNN, Bellingcat published what they had in a series of explosive, drip-fed stories. “We wanted to cause maximum drama,” Higgins recalled, of a decision to save the most incriminating audio until senior Russians, including Vladimir Putin, had had a chance to make a comprehensive denial. “Very satisfying... There’s nothing I’ve enjoyed more than giving Putin a bloody nose like that.” The story secured record traffic for Bellingcat and ended up forming a centrepiece scene in Navalny, an Oscar-winning documentary about the dissident. Looking back, Higgins described it all as “great fun... from the comfort of my own home”. The home part of the equation was important to him. “I think it’s empowering, because if I can do it, many, many other people can. A core principle of Bellingcat is to teach other people how to do this, so that one day they might be giving Putin a bloody nose, and if not him, some other terrible dictator.”

Higgins is an anonymous dresser, a fast talker, a reformed shy-guy who says he once had to “reprogram” his brain in order to undertake the sort of public-speaking engagements that now form a large part of his schedule. He has an ego, that much is clear—but there is a pleasing absence of the grand about him, perhaps to do with the fact that he does not see himself as part of the established media fraternity. By my count, Higgins and Bellingcat have published at least two other world-halting pieces of journalism aside from the Navalny story, one of which—their identification of the suspects who carried out the Salisbury Novichok poisoning in 2018—made me stop what I was doing when I read it and, like an impressed person in a cartoon, actually gulp.

In the Midlands office I confessed to Higgins that I’d tried to write an investigation of my own into that unsettling case in Salisbury, when the former Russian spy Sergei Skripal was targeted for murder, alongside his daughter Yulia, while living in sleepy English exile. The assassination attempt involved such irresponsible methods that a police officer was hospitalised and one civilian was killed through exposure to Novichok months later in a neighbouring town—her husband had found a perfume bottle containing the substance. I had rushed to the scene in the immediate aftermath of the Skripal poisoning and clustered at the do-not-cross lines with dozens of other notebook-wielding reporters. I met with ex-intelligence officers from both the UK and Russia. All a total waste of time—at least compared to the brisk and efficient job that was done at Bellingcat.

Higgins’s contributors stayed away from the initial scrum in Salisbury. In fact, they didn’t see any desperate need to visit the city. “At Bellingcat, we watched,” Higgins recalled in a 2021 book, We Are Bellingcat, “awaiting a point of entry.” They waited half a year. My story about Salisbury came and went, along with many others that failed to answer the question: who were these assassins? Then British police belatedly released pictures of two Russian suspects and the false names under which they had travelled to Salisbury. “Within days,” Higgins wrote in his book, “we had cracked the case.” Grozev, the talented contributor who later allied with Navalny, pored through hundreds of Russian databases, which included flight manifests. He paid hundreds of euros of his own money to get access to the booking data of different airlines and identity documents held by the Russian state. “Found them”, wrote Grozev in a text message to Higgins and others in the Bellingcat braintrust.

From a distance of a few years, the Salisbury investigation was a good and bad example of the Bellingcat method, Higgins told me. They used plenty of legitimate sleuthing tricks, such as trawling through online yearbook photos, reading military biographies, scrolling through Skype handles—techniques available to anybody with an internet connection. That was the good. What troubled Higgins in hindsight were those payments for private documentation (not something confined to the Salisbury case; elsewhere Grozev has paid five-figure sums of his own money in exchange for documents and records).

From a credo perspective, this paid-for information was problematic because it was not open access. It was therefore against Bellingcat’s guiding ethos: that anybody could or should be able to perform similar investigations if they had the will and the nous.

“It’s very hard to say, ‘No, I’m not going to look into these assassins that are murdering people because it’s not open source’,” Higgins told me. “You kind of get drawn down that path. But over the last year or so, we’ve tried to move away from that and get back to those open-source roots.” He explained: “We started to find it difficult to keep doing that kind of work when we became aware of the risks presented to people doing it… If they [the Russians] arrest you, they aren’t taking you to prison, they’re taking you to an open grave in a forest.” That’s literally what happened to the business partner of one of Bellingcat’s sources on the Navalny story: he was mock-executed. “We had to get [our source] out of the country after that,” Higgins said.

Grozev, Bellingcat’s star contributor, has stepped away from the organisation during the last 10 months or so—amid security concerns that we will come to. As I sat there with Higgins in his office, he seemed to have arrived at an inflection point—attempting to keep up the ambition of the scoops of the previous decade, while trying to turn himself towards the challenges of the future, without quite being sure what those challenges might be.

Bellingcat emerged out of the UK’s austerity era. Higgins was born and raised in Shrewsbury. By the 2010s, at a time when councils around the country were having their budgets throttled by Cameron and Osborne’s government, he was a 30-something college dropout working as an administrator for a refugee charity in Leicester. That charity lost its contract, at which point it entered a period of managed decline. Employees left one by one. Soon, Higgins remembers, “it was me and the maintenance guy. I would get in very early, about 7.30am. This was before I had kids. I would get all my work done in a few hours. And then…”

And then he would set about some citizen journalism. Civil war had broken out in Libya and Syria. Higgins, a keen reader of the news, in particular the Guardian’s Middle East coverage, had noticed that traditional media outlets were slow to make use of the civilian- or soldier-shot pictures and videos that were emerging out of conflict zones via social media. He started commenting below the line on the Guardian and later publishing posts to his Brown Moses blog. (That name comes from a Frank Zappa song; Higgins is a fan.) Word about Brown Moses spread. Information he had dug up found its way into mainstream news coverage and was once cited in a front-page story in the New York Times.

Wasting his offline days in a dying office, online Higgins was more and more of an authority, a respected and sometimes plagiarised source of remote reporting. His niche, he later wrote in his book, “was the detail. I never attempted to tell a complete story, as a news reporter strives to do. I unearthed nuggets that others might use.” Scrutinising hours and hours of raw footage, searching for details and verifiable facts that war reporters hadn’t or wouldn’t notice, Higgins in his Brown Moses guise helped texture and fill in western readers’ understanding of a distant conflict.

A core principle of Bellingcat is to teach other people—so that one day they might give some terrible dictator a bloody nose

“It was half an hour’s work,” he told me, of the day in summer 2011 that he accidentally stumbled upon the now-widespread journalistic technique called geolocation. In his empty office, “twiddling my thumbs”, Higgins set himself the challenge of identifying the city or town in the background of a newly emerged piece of footage—a selfie, essentially—posted online by a Libyan rebel soldier. Higgins figured, if he could prove that the rebel was walking around in a particular part of the country that was supposed at the time to be controlled by Muammar Gaddafi’s loyalist troops, he would have proof that the frontline of the civil war had shifted. He took a piece of A4 paper out of the office printer and, cross-referencing details in the background of the picture against Google Maps, sketched out a rough street map. “With a bit of a brain shift,” he wrote later, “you could construe video images from a top-down perspective… It became a matching game. I had stumbled across ‘geolocation’, as we came to call it—the first technique of the digital detective.”

Over subsequent years, more techniques would be added to the digital detective’s playbook. Higgins and others like him make habitual use of Google Earth, Wikimapia, an app called Pixifly that helps them search Instagram posts according to time and place, and SunCalc, an app that helps them determine the length of shadows in photographs and video stills. Where software doesn’t exist they have programmed it, for instance, creating tools to find satellite pictures free of clouds or for figuring out when a TikTok video went live. They have taught themselves the patience to trawl through hours of video; shocking footage; mundane footage; footage recorded at weddings and graduations and children’s birthday parties as well as footage recorded in the scatter zones of crashed aircraft; aboard tanks; at public executions. Which leads to another important entry in the digital detective’s playbook: learn to recognise the signs of secondary trauma in yourself.

“There are different kinds of trauma you can get from this work,” Higgins told me. He has known contributors to feel dizzy, depressed. Early in his investigative career (trying to find proof of the use of sarin gas in one of Assad’s bombing attacks on his own civilians) Higgins spent hours studying social-media footage of dying adults and children, trying to spot incriminating signs of altered pupils. “Not good,” was how he described the effects of that activity on his health. Later, when he was looking through images of the wrecked MH17, the Malaysia Airlines plane that crashed in 2014 over Ukraine killing hundreds of passengers, Higgins came across a picture of a stuffed toy. “A Miffy rabbit, do you know those? My daughter had the exact same one.” He found the picture of the toy rabbit harder to process than gorier, more explicit images of the same disaster. “It was just very upsetting,” he told me.

The MH17 disaster—up there with Salisbury and Navalny in Bellingcat’s landmark investigations—happened to take place just a few days after Bellingcat went live. Higgins had finally lost his job at the refugee charity. He worked for a pipe company in Leicester for a while, then did admin for a retailer of women’s underwear. He had applied for journalistic traineeships, including at the BBC, but never heard back (despite the fact that the broadcaster had made use, he said, of findings he had publicised via his blog). Frustrated, broke, starting to outgrow Brown Moses, Higgins was encouraged by readers of his blog to formalise the operation, leading to a crowdfunding drive and the foundation of Bellingcat.

It was the journalist Peter Jukes, an admirer of the way that Higgins and his collaborators held powerful global actors to account, who suggested the name Bellingcat, a riff on a fairytale in which cunning mice hang a bell on a cat so that however sneakily it tried to move against them, they would know what it was up to. The cat-like Russian state denied military involvement in the downing of MH17, despite mounting evidence that Russian-backed soldiers had ground-launched a missile at the plane by accident. Mice-like, a newly formed core of Bellingcat contributors went to work to prove military involvement. Piecing together digital scraps, sifting through hours of dashcam recordings hoping for glimpses of clues, they were able to chart the movements of the renegade unit that fired the fatal missile.

Whenever they were stumped in this work, Higgins asked for and received help from followers on social media. After finding a useful piece of video that potentially identified the route the missile was transported by, Higgins tweeted: “Gold star sticker to the first person who geolocates this video.” Minutes later, they had a hypothesis that would help them piece together the where of the crime. Soon they had also figured out the who and the likely why (a colossal fuck up that Russian generals tried to cover up with falsified digital evidence). Putin’s state media agency, RT, started calling citizen sleuths like Higgins “a dangerous trend”. Higgins fully agreed.

Bellingcat’s reporting on MH17 established its reputation, a reputation that was lacquered four years later by the Salisbury scoop and then, two years after that, the Navalny scoop. Higgins has been able to expand his permanent staff from one to six to 18 to over 40 at the time of writing, and open a physical office based in Amsterdam. There is an executive board that Higgins sits on as chairman alongside a business director, Dessi Lange-Damianova, and a training director, Giancarlo Fiorella. “We power-share,” Higgins told me, explaining that this came about in part to avoid a Wikileaks-style scenario where the whole thing became a one-man psychodrama. (“I didn’t want it to be the Eliot Higgins Show.”) There are separate supervisory and advisory boards to provide oversight. Top salaries are publicised on the website: Higgins and his executive colleagues pay themselves €90,000 a year, more than he got working in pipes but also not a fortune.

It’s very hard to say ‘No, I’m not going to look into these assassins that are murdering people because it’s not open source’

The outfit is funded by donations—including anonymous donations—and by income from its training division, which teaches the tricks of the trade to aspiring digital detectives. Just over a third of its overall funding comes from nonprofit organisations; just under a quarter comes from individual donors; 13 per cent is income it generates itself. Smaller wedges come from lotteries and private companies. In the mid-2010s, Google donated a high five-figure sum to Bellingcat, apparently a gesture of encouragement as Higgins and his team were finding their feet back then. “They didn’t get me to sign for it,” Higgins recalled, still a little surprised, “they just transferred it to my bank account.” He has several times had to defend himself for once accepting money from the National Endowment for Democracy, an organisation set up by the American government and which some sceptics believe has links to the CIA. Higgins doesn’t buy this theory. “There’s such thin evidence… one former CIA guy made that accusation in the 1990s and it was never backed up.” But in recent years Bellingcat has “moved away from taking money that comes from organisations that are mostly funded from a single government—just so in the future people can’t use that lame attack on us again. It’s annoying.”

Bellingcat’s work is mostly conducted over Slack these days, on which app the larger Bellingcat operation has dozens of private or semi-private channels. Frequent contributors get invited in to certain Slack channels, which often serve as pitching rooms for story ideas. While I sat with Higgins in Leicester, he scrolled through these Slack channels. There was one specifically for the Ukraine War and several more for Russia-related global activities. There were channels called “Far Right Monitoring”, “Financial Investigations”, “Chemical Weapons” and so on. In one Slack channel (“Bellingcats”) staff and contributors were invited to share photos of their pets. Another (“Bellingcooks”) was full of recipes. As Higgins scrolled down the list, my eye was caught by a channel called “Drama”.

Drama. There’s been plenty of that.

In 2021, Yevgeny Prigozhin, the late leader of a mercenary army, took issue with some reporting of Bellingcat’s that portrayed him as the leader of a mercenary army. Instead of suing the organisation, Prigozhin (or rather his solicitors, London-based and well-schooled in the absurdities of British libel law) went after Higgins personally over social media posts he had made to promote the reporting. The UK Treasury, then under Rishi Sunak’s chancellorship, apparently helped Prigozhin to circumvent its own sanctions. As the legal commentator Peter Geoghegan described this, um, unusual situation in the London Review of Books: “A man who [was] forbidden to enter the UK or hold a British bank account was given permission to harass a British journalist.” Higgins, helped by colleagues at Bellingcat to pay for lawyers of his own, ended up accruing £70,000 in costs despite the claim later being thrown out.

“It started out as a nightmare,” Higgins said to me in his office. “But it worked out better for me than it did for him.” Prigozhin was killed in August. I asked Higgins what he thought when he heard the news of Prigozhin’s demise. He said: “The world’s a better place.” I asked him how he felt, two-and-a-half years on, about the Treasury’s curious involvement in the case against him. He said: “It was probably a Monday morning in the civil service and they hadn’t had their coffee. There probably wasn’t any malicious intent.” I asked him what happened to Bellingcat’s 70 grand. Higgins wasn’t sure; there were complications involving Prigozhin’s estate. “But if I don’t get the money back because he’s dead, I’m willing to take the loss on that.”

I was fascinated by the breezy tone Higgins tended to adopt when discussing dangerous men like Prigozhin and Putin. The privately anxious often tend towards public bravado, of course. But there was something else: a stubbornness about being cowed by bullies, perhaps. “I take necessary precautions as best I can,” he said, when I asked him if he was ever concerned about his personal safety. “It depends on the context. Like, if I’m in a hotel, I won’t have room service. If they leave out complimentary chocolates or something, I have to flush that away. I can’t stand having it in my bin. I’m thinking about it being GRU poison.”

He recalled travelling to Amsterdam in 2018, right as Bellingcat’s big Salisbury story was about to publish. He was staying in a familiar hotel in the city. “I got a knock on the door. It was a guy in a suit. Name badge. He said, ‘Mr Higgins, we want to thank you for staying in this hotel 10 times.’ He gave me some free biscuits. I thought, ‘Okay, I’ve literally never heard of anyone doing that before’.” Higgins spent half the night Googling, do hotels give gifts for staying 10 times? He had already thrown everything away. He had washed his hands and checked his pupils for dilation. “The next morning, when I went down to the lobby, the receptionists asked me if I enjoyed the complimentary cookies.”

But seriously, Higgins said, he was more worried by random, unhinged individuals—people who have come to dislike him online—than he was by any state actor. He often gets into arguments on Twitter. He has had a few stalkers, as well as an inexplicable series of run-ins with a pressure group formed of European farmers who, Higgins told me, had taken against some statement by him and kept appearing at his speaking engagements. “Sometimes I still do have moments of anxiety,” he said, recalling a recent panic in a hotel room when the air conditioning unit started emitting a sulphurous smell. “They pass, these moments. I’m not going to let my life be ruled by anxiety of being assassinated. I would say Christo [Grozev] has had more problems with that, as you’ve probably read.”

Yes. Retaliation directed at some of Bellingcat’s key contributors, individuals who live in Russia or have close links to the country, has been severe. Roman Dobrokhotov, a Moscow-based journalist whose online publication The Insider collaborated closely with Bellingcat on the MH17, Salisbury and Navalny stories, had his home raided by state authorities in 2021. Fearing for his life, Dobrokhotov walked across the border into Ukraine. As for Grozev, whose digging and database sourcing was fundamental to Bellingcat’s biggest scoops, he was arrested in absentia by a Russian court despite not being a Russian national. In fact a Bulgarian national, resident for many years in Vienna where he lived with his wife and children, Grozev recently told the Financial Times of an extraordinary warning he was delivered by Austrian authorities.

Leave Austria (Grozev says they said) because we can no longer protect you from the Russians. Grozev is now living in America without his family. In March, he missed his father’s funeral. Not that having a Kremlin-made target on his back has made him any less belligerent. In the summer he told the FT: “The Russians are spreading legends and narratives about me that we are CIA because the alternative would make them look so weak—that they are being beaten by journalists. That’s not acceptable to their pride.”

Is Higgins ever concerned about his personal safety? ‘If I’m in a hotel, I won’t have room service’

The CIA smear and others like it have been a source of mild but persistent drama for Bellingcat since its foundation. As recently as the spring, Elon Musk dismissed the entire Bellingcat project as a “psyop”, a reference to psychological operations practised by military and intelligence services.

An awful lot of sceptical people think that Bellingcat’s reporting is too good to be true. They think that the organisation gets its goods from one or other intelligence organisation, if not in the US then in the UK. Higgins denies this. But he would. I asked him, if he was a digital detective who existed outside the Bellingcat bubble, how would he dig into whether this organisation had links to spy agencies? Higgins pondered this, then said that he would look at the organisation’s structure, how transparent it was about its money, its information sourcing. (He said that this was one of the reasons Bellingcat was set up the way it was, with his salary and others made plain on the website: to combat conspiracy-mongering.) When he ran out of ideas he acknowledged that, eventually, open-source investigation hit its limits. Some things just had to be taken on trust or not taken at all.

It was time for me to leave his office. He had to get some work done before the weekend. Bellingcat’s next story, then taking shape on its Slack channel “Far Right Monitoring”, was an exposé of a fantasist who claimed to be a dangerous mercenary when he wasn’t. As well as keeping an eye on that, Higgins was about to spend time answering emails for a documentary on MH17. He had a staff retreat to think about; a paid corporate speech to tinker with as well as a university lecture; a journalism award to accept in Gothenburg. There weren’t many pictures on display in his office, but as I was leaving I noticed a holographic image on a shelf of a mouse scurrying across a computer keyboard. It put in mind those earlier, friskier days of the Bellingcat experiment, when Higgins and his collaborators, self-acknowledged mice, scurried under the feet of mighty governments and, occasionally, made them whimper.

In October, as violence took hold of the Middle East, Palestinians killing Israelis and Israelis killing Palestinians with a ferocity that was hard to make sense of, a familiar routine played out in the wider world. People miles away from the conflict zone turned to the internet to try to find out what was happening. They encountered a space brimming with nonsense, best guesses, half-truths or quarter-truths. “Grift” was a word that Higgins kept using when I met him. It was his way of describing the most destructive kind of internet lie, the deliberately seeded untruth that flourishes all too well on social media. I thought of “grift” often during those early days of the Gaza violence, when fabricators, guesswork merchants, propagandists on both sides seemed at their most prevalent and divisive.

When Higgins and I spoke again in November, he sounded changed, fatigued by events as the conflict in Gaza entered its second month. If the Bellingcat project was to count for anything, Higgins told me, it must quash or at least reduce the power of the internet lie. Society needed this more urgently than ever. As Higgins saw things, people with sympathies on both sides of the conflict—understandably confused, sad and scared—were tending to huddle in online spaces where they could expect to hear confirmation of what they already believed or suspected. Grifters, dealing out fake news and conspiracy theories to different camps, were thriving.

Higgins partly blamed Elon Musk’s slow and miserable quasi-deregulation of Twitter (or X, as Musk wants us to call the social-media tool now, as if in acknowledgement of its no-go toxicity as an online place). “Oh, he’s made a great environment,” Higgins said wryly—“for the spread of disinformation.” There were times during the first weeks of the conflict in Gaza that Higgins removed Musk’s app from his phone. He slunk back to the service eventually, as so many of us do, despite our better instincts. These were instincts that Higgins still hoped to tap, he told me. I knew that Bellingcat had been slowly deprioritising the singular, smash-and-grab scoops that made it famous. Instead, it was trying to propagate the investigative techniques that underpinned those scoops. Higgins intended to ramp up those efforts. Bellingcat was involved in the launch of a new investigations lab at a Dutch university. He had once hoped to teach people the trick of giving the Putins of the world bloody noses. Now, it felt imperative simply to teach and spread the tricks of basic factual verification.

When a hospital in Gaza was bombed in mid-October, there was widespread confusion about the culprit. Into a very human gap of instinctive empathy and shock, deliberate misinformation flooded—all the worst that the modern Musk-y internet could muster. I suggested to Higgins that Bellingcat would once have devoted investigative resources to figuring out what really happened to that hospital. “Things are moving so fast [in the region],” he said. “We can focus on one incident, look properly at the disinformation there. And by that time there’s been 10 equally bad incidents.”

He continued, “The question is, how do you create something useful from this? It’s one thing to write all these articles about all of these terrible things that are happening—but does that make any difference, ultimately? Because what we’re seeing in the way people approach Israel and Palestine, they aren’t really looking for truth, they’re looking for something they can bash you over the side of the head with. And that doesn’t really bring us closer to solving fundamental issues that are at stake both with Israel and Palestine but more broadly with the way our society consumes information.”

October’s events in the Middle East seem likely to have as wide a radicalising circle as any in memory; it shouldn’t be a surprise that Higgins has become a little radicalised himself by the apparent hopelessness of it all. Jeremy Paxman once described him as a journalistic hero. With the collaborators he has teamed up with, Higgins has achieved sustained journalistic success beyond my or most other reporters’ wildest imagining. To hear him question the efficacy of investigative reporting—“Does it make any difference, ultimately?”—disturbed me enormously. But Higgins went on to insist that while Bellingcat’s editorial arm would continue to pursue compelling stories, its broader organisational focus had to be on the causes of misinformation, not just the symptoms.

Otherwise, Higgins guessed, we were likely to end up with a society “where a truth doesn’t really matter anymore. Where it’s more about what you feel is accurate rather than what is accurate. Where people never know what’s really going on. Where people get to pick-and-choose whichever version of reality they prefer.” Bellingcat’s motto has been to identify, verify, amplify. Things being as they are in the world, that might already have changed. Verify, verify, verify.