Russia’s invasion of Ukraine early on the morning of 24th February 2022 shook the world in ways eerily reminiscent of the Great War’s outbreak in 1914. As a century before, the growing risk of a conflagration had been obvious for all to see. An early sign was Vladimir Putin’s rambling pseudo-historical essay of the summer of 2021, menacingly entitled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians”. There followed over winter the deployment of up to 190,000 Russian personnel with their war machines all around Ukraine’s frontiers. In the final weeks before the onslaught, western powers forewarned by their intelligence agencies abruptly evacuated their embassy staff from Kyiv. Yet on 24th February, when Russian missiles shrieked through Ukrainian skies and long Russian military columns rumbled over the border, feelings of shock and horrified incredulity were, just as at the start of the Great War, palpable far beyond the conflict zone. How, people wondered, could there be war in 21st-century Europe, a continent rich, free and so long at peace?

In the Polish city of Przemyl, lying just behind the Ukrainian border, the resonances of 1914 were even stronger. Przemyl was once a fortress city guarding the east of the Habsburg Empire. When, at the start of the Great War, Tsar Nikolai II’s Russian Army struck westwards and appeared poised to overrun central Europe, it was to Przemyl that floods of refugees fled seeking sanctuary. In 2022, those first desperate scenes of 108 years before were repeated, as train after train packed full of Ukrainian women and children fleeing another Russian army pulled into the city’s pretty Habsburg rail station. As the main point of entry to Nato-protected territory, Przemyl again promised safety for frightened and exhausted people displaced by war. In the conflict’s first months, this small city of 60,000 welcomed over 1.2m refugees. A spontaneous and hugely generous civic effort offered help and housing. For the first time since 1914–15, Przemyl drew global attention.

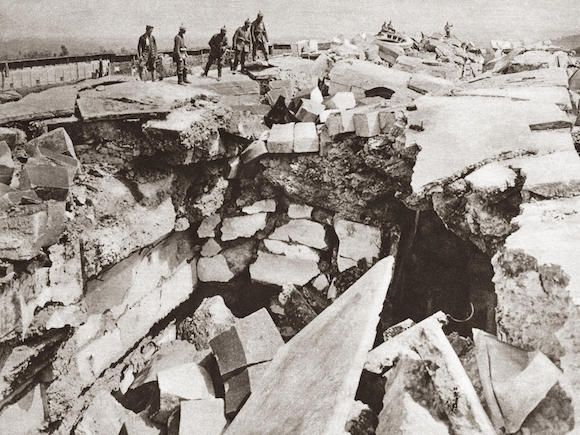

A century earlier, the city had blocked the Russian Army’s path and was subjected to that horrific conflict’s longest siege; 181 days of bloodshed, suffering and extraordinary defiance. The story of that siege appeared to me, at least until recently, as a historical episode important both for its decisive impact on the First World War and as a crucial yet overlooked starting point for the horrors which ravaged the wider region in the years that followed.

Today, the war raging to the city’s east has exposed another pressing contemporary relevance. The story of Przemyl’s siege, with its mass conscript armies, ferocious winter warfare, wretched civilian suffering, and frighteningly modern ethnic cleansing, links the past tightly with our own time. Tsar Nikolai II’s violent bid to seize, hold and reshape the land and people around and to the east of Przemyl is a stark reminder that today’s Russo-Ukraine War, although launched by one man, is also a child of dark currents in Russian history.

Vladimir Putin’s violent ambitions in Ukraine, and the ideology behind his denial of Ukrainian nationhood and insistence that Ukrainians are merely a subordinate branch of the Russian people, has its roots in Russia’s imperial past. Tsar Nikolai II’s wish to create “a Great Russia to the Carpathians”, announced in April 1915 when his army briefly stood triumphant in what today is western Ukraine, and the modern Russian state’s aggression are both underpinned by a common racialised nationalism. Putin’s war is not just a legacy of the Soviet Union’s crumbling but a replay of the Tsar’s failed attempt to claim all Ukrainian-inhabited lands for Russia.

Some power calculations remain constant: the historian Dominic Lieven’s observation that the Tsarist state needed Ukraine’s people, agriculture and industry to be a “great power” holds true for modern Russia. Today’s brutality parallels that of 1914–15, for it is motivated by the same violent and deeply entrenched nationalist ideology. Both the Tsar’s and Putin’s armies have behaved viciously toward people whose existence contradicts their vision of “primordial Russian land”. Jews were the major victims of 1914; beaten, murdered and, in Przemyl after its surrender, cleansed totally. Yet the Tsarist military also waged a fierce and disturbingly familiar assault to eliminate Ukrainian identity, purging Ukrainian intelligentsia and shutting down Ukrainian cultural and educational institutions. Ukrainian books were confiscated and Russian histories imported for use in Ukrainian schools; also a priority today for the occupiers of devastated Mariupol. Extreme violence was and remains an authoritarian tool to transform populations. In 1914, people spoke with horror of Russian crimes at Brody and Lviv; today notoriety has passed to Bucha, Irpin and Izyum.

The Tsar’s military campaign led to a gruelling attritional struggle which eventually destroyed his regime. Though today’s war is fought with very different weapons, militarily too there are striking continuities. In 1914, battle-hardened and after a decade of modernisation, the mighty Tsarist army was expected to be a “steamroller”, crushing all before it. Putin’s military too had enjoyed years of investment before the Russo-Ukraine war and was widely rated as among the world’s most formidable. Yet both armies disappointed. The reasons are astonishingly similar: a persistent culture of corruption in state and army, inflexible senior commanders unable to coordinate dispersed forces, institutional neglect of logistics and secure communications, poor officer-man relations and a small and badly trained non-commissioned officer corps all degrade Russian combat power. A turbulent century separates these armies, punctuated by revolutions and regimes of radically differing ideology, and yet the old French adage applies: plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Nevertheless, the future is open. The early victory outside Kyiv and the immense courage and sacrifices of its people in this terrible war have already secured Ukraine’s survival as an independent nation. Its army’s recent advances in Kharkiv and Kherson have given efforts to liberate Russian-occupied territory further momentum. Yet the First World War and, above all, the gruelling siege and extreme violence around Przemyl in 1914–15 are reminders that the present struggle is about more than one autocrat’s vanity. Russia’s ambitions over Ukraine and its people have a long and blood-drenched history. Thwarting those ambitions and closing that history for good will not be easy. The current war will be very hard fought.