It looks like we could fairly soon be leaving the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Farage long ago made this his next Brexit, as a supposed cure for interventionist human rights lawyers stopping immigrant deportations. True to their current form in chasing after Reform UK, the embattled Tories have now said the same. Keir Starmer, meanwhile, has split the difference, committing a few days ago to “look again” at the ECHR in order to facilitate deportations.

Starmer’s intervention, coming as it does from a former human rights lawyer, plays straight into support for Farage. I doubt the prime minister has any actual plan for renegotiating the ECHR, which would be hugely difficult and lengthy, given that it is a treaty of 46 nations. But with these remarks he has substantially delegitimised the ECHR, having previously—with his friend Richard Hermer, the attorney general—refused to accept that there was incompatibility between tackling asylum abuse and human rights law.

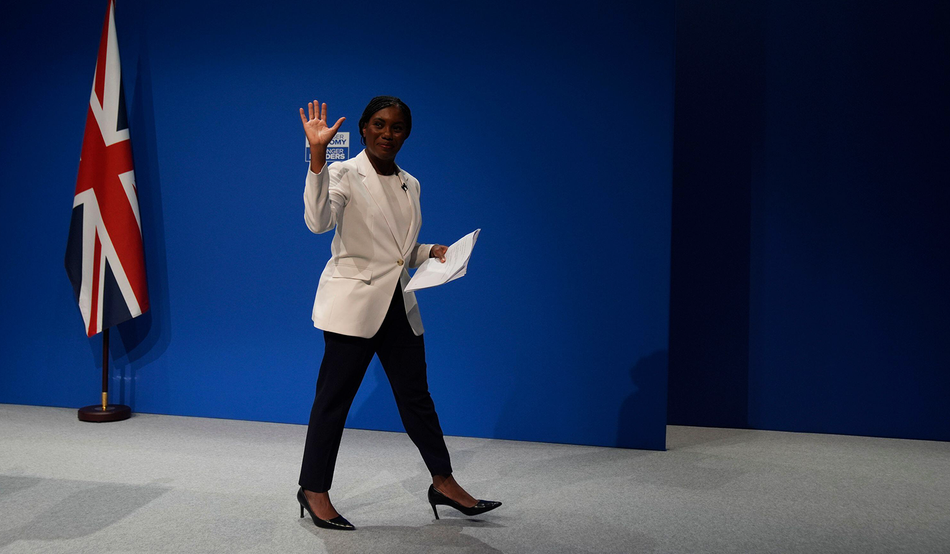

Then there is the new home secretary, Shabana Mahmood, who was appointed with the challenge from Reform in mind. She immediately suggested a draconian tightening of the regime under which migrants can apply for settled status (or “indefinite leave to remain”), also splitting the difference with Farage. Last month, the Reform leader proposed to scrap that status entirely and deport previously legal migrants wholesale. This week Mahmood proposed big curbs on pro-Palestinian demonstrations.

It won’t, I think, be long before Mahmood starts overtly attacking the ECHR and briefing about the need for Starmer’s review to be bold in curbing human rights judges. It wouldn’t surprise me if, in due course, she runs to be Starmer’s successor on a “Reform Labour” platform of forestalling Farage by pulling out of the ECHR entirely.

So what actually happens if we leave the ECHR? “Everything and nothing” is the answer.

The formal act of leaving means withdrawing from the Convention and from its two associated postwar, Strasbourg-based institutions: the European Court of Human Rights and the Council of Europe. The symbolism of this would be huge, but the immediately practical effect would be limited, because the rights-based provisions of the ECHR are already entrenched in UK law through the Human Rights Act (1998). It is British, not European, judges who are the main guardians of the ECHR, as the last government found when it proposed deporting asylum seekers to Rwanda, a country with a poor human rights record.

Furthermore, for all the arguments about individual deportations of asylum seekers and other illegal migrants to “unsafe” countries, no government of recent times has attempted a deportation policy which takes rights of residence away from legal migrants or British citizens (apart from those convicted of offences). Even Enoch Powell, in his “Rivers of Blood” speech in 1968, did not propose forced deportation of legal immigrants. Notably, all EU citizens resident in the UK at the time of Brexit were allowed to remain thereafter.

So the big question is: having withdrawn from the ECHR, what could a prospective government do next that wasn't possible before withdrawal? In particular, what would it do in terms of the existing UK legal protection for human rights? And what would it do in terms of new policies and practices?

The brutal reality is that, outside the ECHR, there is virtually nothing a government could not attempt to do if it commanded a parliamentary majority. If, for example, a Farage-led government repealed the Human Rights Act, it could then sack judges and replace them with partisan ones; sack civil servants en masse and replace them too with partisan appointments; deport British citizens; abolish jury trials; abolish the BBC; dispense with anti-corruption legislation; and even subvert free and fair elections. Such a government would also need to abolish or pack the House of Lords with loyalists—which it could also do, provided that the Commons was prepared to sanction it.

The only other possible constraint is the monarchy and its reserve powers. But these have never been used against a government in the democratic era, and this would be a perilous course.

The key point is that the irreducible core of the British constitution is the doctrine of the sovereignty of parliament. Once the ECHR has gone, that is all you have left.