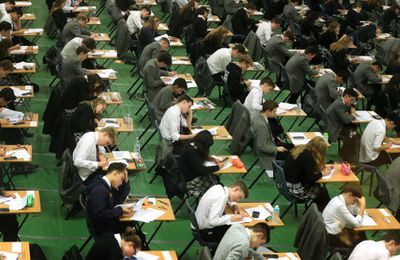

Education, on some measures the UK’s biggest industry after finance, is being corroded by the creeping infiltration of global finance at every level. The primary aim of such companies is usually to extract as much profit as possible from the huge sums being spent on education by governments and individuals, and reward their international investors, most of whom have no intrinsic interest in education or UK society and culture. The result has been lower standards, declining quality and a corruption of the classic aims of education.

Financial companies and private equity (PE) in particular have sought to capitalise on growing global spending on education and training, estimated to be worth more than $8 trillion a year by 2030. Private equity’s business model is built around short-term profit maximisation and two strategies designed to increase the wealth of investors rather than improve learning.

The first, dubbed “buy, strip, flip”, involves buying a firm using borrowed funds, thereby loading it with debt, before slashing costs and selling its assets to boost profits and pay handsome dividends to investors. The firm is then sold on after a few years or, all too often, declared bankrupt, with little regard for the economic and social consequences. The UK already has seen the abrupt closure of private equity-owned care homes for the elderly and for vulnerable children when these were no longer profitable.

One tactic within this strategy is “sale/leaseback”, whereby the finance company sells a property of the bought firm to another, often also owned by the finance company, and then obliges the original firm to lease back the asset, providing a large rental income that is then paid out to investors. Sale/leaseback has been used in the UK primarily by owners of independent schools and for-profit nursery chains but also by academies and “free schools”, as well as by charter schools in the US. In one egregious example, British taxpayers are paying half a million pounds annually for a London primary school to rent its land and buildings from an investment company. The government has also approved state schools to increase their use of leasing arrangements for equipment of all kinds, ranging from computers to lawnmowers to minibuses, creating another profitable income stream for finance companies.

The second strategy is “roll up”, which involves a financial company buying up as many providers as it can, to take advantage of economies of scale and standardisation. This approach is now commonplace for private nurseries and pre-school childcare, on both sides of the Atlantic, where firms aim to create a local monopoly enabling them to raise prices without fear of competition.

Such strategies have a longer history in the United States than in the UK. Private equity and other investment firms began buying up pre-school providers in the late 1990s and supplying a low-cost standardised service, part of what sociologist George Ritzer described as the “McDonaldisation of society”. Annual profit rates of 15 to 20 per cent are the norm in this sector.

The same process is now taking place in the UK, often involving foreign investors attracted by the guaranteed revenue stream generated by the government’s model of subsidising private childcare, as well as cuts in funding for state-provided childcare. Providers backed by private equity or investment firms spend less on staff and charge parents more, while their annual profits average over 20 per cent, double that of other private providers. Those profits are not channelled into expanding childcare provision, but are paid out to lenders, investors and private equity executives. Perversely, by draining funds out of the sector, finance reinforces the already severe shortage of nursery places.

Special educational needs and disabilities

Equally worrying is what is happening to SEND (Special Educational Needs and Disabilities) schools. Local councils have a statutory obligation to provide suitable schooling for children who need extra support, but have not been given the resources to meet rising demand themselves. Instead, paradoxically, they have had to turn to higher-cost private providers, incurring huge deficits that the government has allowed temporarily to be moved off council balance sheets to avoid them going bankrupt.

Private equity has moved in, again earning more than 20 per cent profit rates. One child’s place in a private provider costs a council £61,500 a year on average, compared with £23,900 in state schools. In 2022-23 alone, private operators netted £2bn in fees paid by cash-strapped local authorities. No wonder a report from 2024 for local authorities concluded that “SEND represents an existential threat to the financial sustainability of local government”. That threat remains despite the government’s announcement in December that it will absorb the off-budget deficit from 2028-29, as there is no guarantee that SEND funding will be sufficient to reduce reliance on private providers.

Schools

Even state schools are not free from private equity and financial capital. Successive governments have encouraged “business-school partnerships”, whereby companies or banks help support state schools. The Bridge Academy in the London Borough of Hackney is close to the City of London headquarters of Swiss bank UBS, which contributed funds to build the school. Up to 1,000 UBS employees volunteer at the school each year, from sitting on the governing body to running activities and mentoring.

Meanwhile, finance has come to dominate the growing phenomenon of for-profit global school chains, which include a number of independent schools in the UK. UK-based Inspired Education Group, owned by a consortium of private equity firms, was founded in 2013 with four schools. It now has 125 schools and nurseries (15 in the UK), with 95,000 pupils in 30 countries. Nord Anglia, another UK-based chain owned by foreign investors, has more than 80 schools in over 30 countries, with more than 100,000 pupils and in excess of 13,000 staff. Oakley Capital, a UK-based private equity firm with a stake in the global school chain Affinitas, has invested in the private school attended by Prince George and Princess Charlotte.

Supply teachers

Another sphere dominated by finance is the provision of supply teachers. Originally, supply teachers were deployed to fill temporary gaps. But under austerity, especially since the pandemic, they are covering for a chronic shortage of permanent teachers. Today there are about 90,000 supply teachers in the UK, most contracted to private agencies, which act as labour brokers. One of the biggest is the Edwin Group, owned by an American private equity firm, which supplies temps to more than 4,500 schools. Typically, agencies pay supply teachers about 40 per cent less than regular teachers, while charging schools almost double supply teacher wages. This is absurd.

Universities

At university level, finance has also been making inroads—initially in the US which has a large number of private higher education institutions, but increasingly in the UK, France, Germany and elsewhere. Several private equity-financed American universities have gone bankrupt or been involved in fraudulent practices, leaving huge numbers of students stranded. A study of US higher education institutions showed that when private equity becomes involved, spending on actual education went down, fees went up and fewer students graduated.

The UK is now exposed to similar risks: in July 2025, a Wall Street private equity fund bought a 50 per cent stake in Arden University, Britain’s fastest growing university, which is privately owned. One of its partners, Bolivian-American billionaire Marcelo Claure, was installed as chair of the university’s board with ambitious plans for an AI-directed expansion. A British university with 40,000 students has become a commodity, owned by foreign interests.

Private equity firms are active in the lucrative business of student recruitment, too. Most British universities are spending a lot of money on trying to lure foreign students, who pay higher fees, through specialised recruitment firms or their own offices in Chinese and Indian cities, and elsewhere. On one estimate, UK universities paid an estimated £500m in agent commissions in 2022. The dominant firm is private equity-financed SI-UK, which has partnered with more than 100 universities and has around 100 offices in 40 countries.

Student accommodation

The three biggest owners of purpose-built student accommodation in the UK are all financial firms, including iQ Student Accommodation which is owned by American private equity giant Blackstone, the world’s biggest private landlord. They have focused on higher-quality, higher-priced accommodation, targeting foreign students from rich families. One could argue that, in so doing, they share some responsibility for putting more British students into deep debt and forcing others to stay at their parents’ home while commuting to attend classes.

Edtech

“Learning products” or education technology (edtech) are another rewarding area for financial capital. These account for a rising share of spending in schools, universities and institutions for “lifelong learning”. Private equity firms are now so powerful in this sector that they can shape the curricula in schools and universities, playing a role in determining what is taught, what is not taught, and how students are assessed.

Apprenticeships

Finance has also seen rich pickings in the supply of apprenticeships. In 2016, Tony Blair’s eldest son, Euan, set up Multiverse as an apprenticeship broker, gaining income from the apprenticeship levy, a government tax on large employers, in return for supplying firms with workers provided with low-cost on-the-job training, mostly in digital technologies. In 2022, after several funding rounds from venture capital, his firm was valued at £1.7bn, the UK’s first edtech “unicorn”. Although the training has never been evaluated, and although his firm has yet to turn a profit, it was allowed to issue BSc degrees (making a mockery of university degrees). At the age of 38, Blair was awarded an MBE for “services to education”.

Multiverse aside, private equity now dominates apprenticeship training in the UK, and increasingly that is led by non-British firms. By 2023, eight of the ten largest training providers by apprenticeship starts were majority-owned by private equity firms or other global investors, and of those only four were headquartered in the UK.

Private finance is trying to dominate the whole education “ecosystem”. As it does so, a greater share of the money spent on education goes to investors, while the supply of services becomes more expensive, less reliable and more controlled by foreign finance.

Thus, while more is being spent by governments and individuals on education than at any time in history, much of that spending is not going on improved education but on rewarding investors—and with the growing influence of foreign finance the system risks drifting slowly out of British societal control.

This article draws from Guy Standing’s new book, “Human Capital: The Tragedy of the Education Commons” (Pelican).