When I was a boy, neo-Nazis threatened to march on Skokie, Illinois, a town with a disproportionate number of Holocaust survivors. Aryeh Neier, then president of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), defended the rights of the skinheads eventuating in a book, Defending My Enemy. The ACLU lost a sizeable number of paying members. Yet Neier cherishes that the absolutist position on speech—I might hate your words, but I shall defend to the death your right to say them—was fervently debated at dinner tables across the country, perhaps for the first time.

Fast forward almost half a century to the crisis surrounding speech in the United States today and edifying conversation has been swapped for rancour and recrimination. Only a few years ago, it seemed that a censorious left was swinging its bat, taking down all manner of people for reasons large, small and unfounded. “Getting cancelled” had become as regnant a concept in the culture as getting dissed, though with impacts far more consequential.

The genocidal war in Gaza flipped the ideological script. Students on campus, often of a left-wing sensibility, peacefully and at times intimidatingly demanded accountability for the crimes being prosecuted. But some of those perturbed by this sought to see the protesters muzzled. Conservative outfits such as Accuracy in Media, a media watchdog, took pains to restrict their speech, underwriting trucks that doxxed people, emblazoning protesters’ names on their sides as they drove around town, so that future firms would think twice before hiring them. The Trump administration wilfully joined the melee, making sensationalist claims about antisemitism running amok from sea to sea, or at least from university to university. Quashing unwanted speech became a racket to strip universities of resources and academic freedom. Defending my enemy had descended to decimating my enemy.

Riven over questions of speech and expression, American civil society is now caught up in a social crisis that has tragically set the stage for political violence. Polarisation may never have been so raw and extreme. And yet there is something instructive about the current conjuncture. Just as the Supreme Court (let’s hope) no longer appears as a neutral body standing above the people and arriving at decisions with transcendence, but instead as a political institution informed by political preferences and commitments, so too might we transform our approach to speech.

The absolutist ideal doesn’t compute for gen Z, for whom speech is always a part of politics. Relatedly, assuming freedom of expression to be an ideology, a closely shared set of commitments that reign as common sense, further redefines the way younger generations apprehend speech. The mainstream views on speech when I was a student have evolved. And that’s okay. Times change, and the standards we once applied may no longer satisfy. Ideologies transform and evolve like language itself.

I can sense the blood pressure of my dear human rights lawyer friends rising. What about that Bill of Rights, which protects fundamental freedoms such as speech? How can we leave speech to the hurly-burly of politics, a domain in which struggles over power and resources are central to human exchange? And does calling freedom of expression an ideology not risk denuding its constitutional power, making it subject to the status of something less “real”, not fixed in stone?

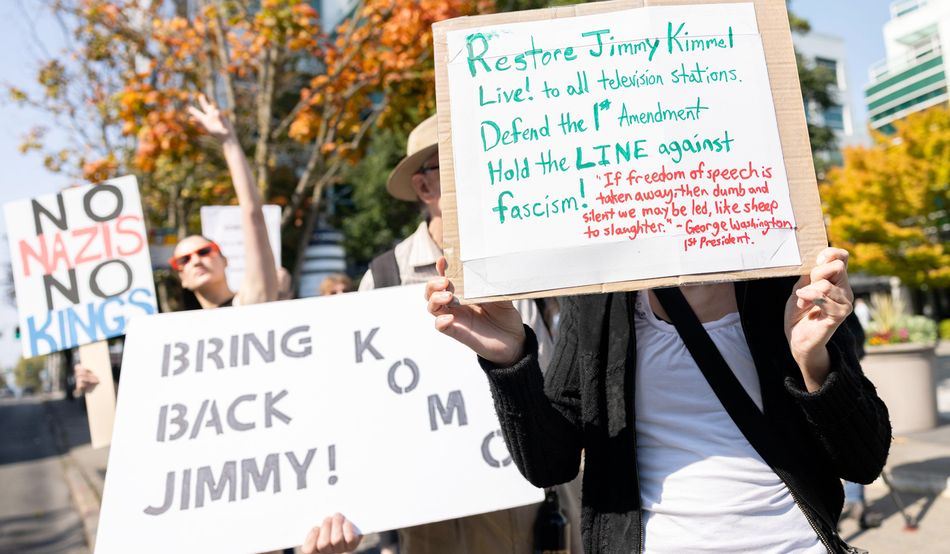

The recent hullabaloo over the suspension of late-night TV host Jimmy Kimmel and his subsequent reinstatement is a clear illustration of how politics affects speech. A lot of factors were at play: citizen outcry; economic interests; moral reasoning; and other political dimensions. To my mind, the case was a strike to the heart of card-carrying originalists who contend that what was written 236 years ago is somehow untouched by history.

This has always been a preposterous notion. We can have laws that determine judicial outcomes based on constitutional interpretation, and at the same time recognise that such laws are not divinely originated. Humans designed them. Recognising the political nature of speech and the ideological fabric it rests upon doesn’t force you to hide behind some Rawlsian screen. It can show democracy at work. And indeed, restrictions on speech, such as the IHRA definition of antisemitism adopted by some US (and UK) universities, are not uncommon in Europe—which never had the absolutist consensus of the US. Learning from Europeans would be an ironical statement amid today’s fraught transatlantic relations.

Next year, the US celebrates the 250th anniversary of its declaration of independence. I vividly recall the over-the-top pomp and circumstance of the country’s bicentennial, a year before that threatened 1977 march on Skokie. Americans were drenched in flag-waving and jingoism the likes of which the nation had never seen (Robert Altman’s film Nashville is still the greatest statement on it). But the bicentennial never became a “teaching moment”, as we now like to say. Would it not be fitting for the semiquincentennial to teach us that speech freedoms don’t exist outside of us, but are actually created by us?