If any idea could unite a fragmented Britain, it might be that we are suffering a free speech crisis.

The political left points to the proscription of Palestine Action and the mass arrest of protestors for carrying banners supporting the organisation. The right points to the jailing of Lucy Connolly and the broader issue of policing social media. The idea of the United Kingdom as an Orwellian nation has international cachet—both US vice president JD Vance and the tech billionaire Elon Musk raise the issue regularly, and Nigel Farage even went to Washington to testify to Congress about it.

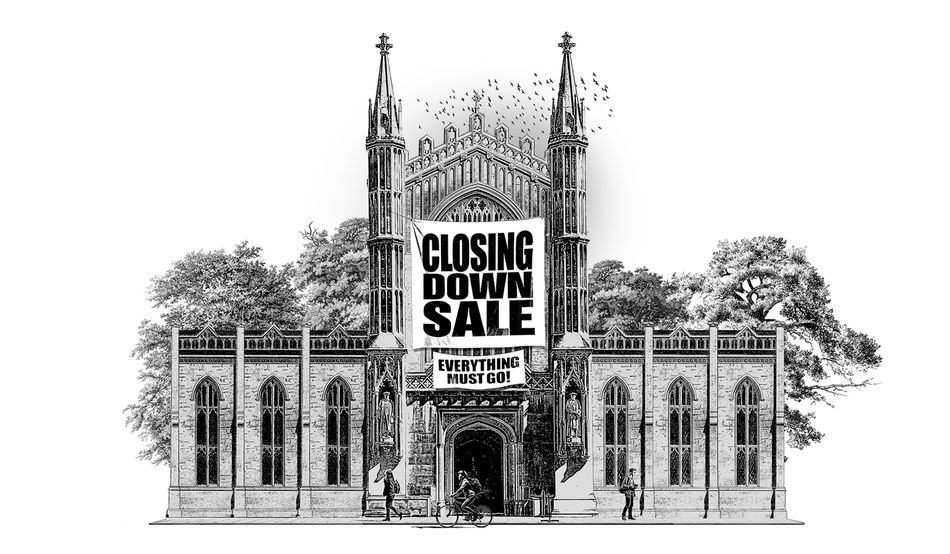

But if the free speech wars have a ground zero, it is surely in the UK’s universities. Depending who you believe, they have either become so full of group wokethink that anyone who dissents is ostracised or even fired, or else has been targeted by politicians who, under the guise of defending “free speech”, are looking to control what academics can teach and research.

The row resulted in the last Conservative government passing a law—the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act 2023—enforcing free speech protections in British universities, and giving the sector’s regulator the Office for Students (OfS) a duty to enforce them.

The University of Sussex became the flagship case for these new rules, as it was issued with a £585,000 fine in March this year “for free speech and governance breaches”. It followed the departure of Kathleen Stock, a professor who holds gender-critical views, from the university, amid student protests calling for her removal.

Officially, the OfS investigation didn’t relate to Stock’s exit, not least because the regulator has no mandate to investigate individual cases. It focused instead on how the university’s rules for protecting trans staff and students interacted with its obligations to protect academic freedom and free speech more broadly.

These rules, among other requirements, give universities “a duty to take reasonably practicable steps to secure freedom of speech within the law” and “to have codes of practice to ensure the protection of free speech”, as well as “to promote the importance of freedom of speech in higher education”.

The OfS not only found Sussex to be in breach of the rules, but found these breaches to be so serious that it issued the largest fine since it was created in 2017. However, several months later, that decision is under serious challenge. The university has accused the OfS of leading an investigation undermined by fatal flaws, bias and poor legal reasoning—and it has been granted a judicial review hearing to challenge it, which will be heard early next year.

The university’s statement of facts, laid before the court, does not go into the trans rights argument, but instead looks at how the OfS tried to enforce free speech provisions.

During its investigation, the university alleges, the OfS interviewed just one person—Kathleen Stock—and did not have one substantive meeting with the university’s management. The eventual fine centred on a single document, its Trans and Non-Binary Equality Policy Statement, which was found to be in breach of free speech rules.

University insiders say that this document, two pages long, was just one policy among hundreds (if not thousands) in a modern university, and did not constitute a core “governing document”—which is what the OfS is supposed to review in such cases.

But more glaringly, the policy was lightly amended from a template guidance form issued by Advance HE, a professional body for universities. Numerous universities used this policy document as the basis for their trans and non-binary policies—but only the University of Sussex has been investigated and fined.

The University of Sussex argues that the Office for Students showed bias, failed to follow its own procedures and got the law wrong—all of which will be for the High Court to decide. But inside the legal complaint is one more argument: that the OfS has for years been ignoring much more blatant free speech violations, despite having them repeatedly brought to its attention.

“The University understands that the OfS has been notified repeatedly about ‘Bible Colleges’, which receive public funds and are subject to regulation by the OfS, and which are plainly in breach of the freedom of speech and academic freedom principles,” it states.

“In particular, these colleges exist for the purpose of promoting and advancing the Christian faith and their governing documents require students to sign statements affirming their Christian beliefs. The University understands that the OfS has taken no action against them.”

These allegations relate to repeated complaints made by the National Secular Society, over a period of years, about around a dozen religious higher education providers registered by the Office for Students. Churches and religious institutions are obviously free to train clergy in private institutions, but once registered with the OfS—which makes them eligible to take students funded by government loans, among other things—they are required to follow all of its rules, including on free speech.

The National Secular Society flagged instances where it alleged the core governing documents of these bible colleges clearly breached free speech requirements. It noted that the stated purpose of Christ the Redeemer College in London is: “To advance the Christian Faith by establishing and maintaining a Bible training institution based solely on the Christian doctrines, principles and faith as set out in the Statement of Faith.”

Elim Pentecostal Church, the parent organisation of, among others, Regents Theological College in Malvern, describes its purpose as being to “spread and propagate the full gospel of our lord Jesus Christ and primarily but not exclusively the fundamental truths set forth in the [church’s] constitution”. The statement of beliefs of the church includes “we believe the Bible, as originally given, to be without error, the fully inspired and infallible Word of God and the supreme and final authority in all matters of faith and conduct”.

Requiring staff and students to adhere to these statements, the National Secular Society argues, was fundamentally in breach of the OfS’s rules on free speech, and of the government’s legal requirements. However, more than three years after the first complaint, the OfS has yet to announce a single investigation into these colleges.

This behaviour creates something of a paradox: one university is fined more than £500,000 for a breach relating to a single document, while other, possibly more flagrant, rule violations aren’t even investigated. If a law protecting freedom of speech is only selectively enforced, it risks having the exact opposite effect to the one intended—letting universities believe that certain types of speech are protected, while others may be punished.

This is weighing on the minds of free speech groups in the UK. “We welcome a serious look at how free speech—which is foundational to academic freedom after all—has been challenged at UK universities,” says Jemimah Steinfeld, CEO of Index on Censorship.

“But we also have concerns about the new legal duties and how they’re enforced. Will they be evenly applied or just in line with the politics of the day? Is fining a cash-strapped university a good solution?

“At the core of the new legislation is a commendable desire to lessen fear on campus. It’s just that the new rules might simply shift where that fear lies rather than tackling the root cause.”

A spokesman for the Office for Students gave the following statement:

“All universities and colleges registered with the OfS need to meet their obligations for freedom of speech and academic freedom. The OfS’s decisions relating to the University of Sussex are subject to ongoing litigation and so we will not comment further at this stage – except to say that we are confident in our decisions in this case and will continue to vigorously defend them.”

Requests for comment to Regents Theological College and Christ the Redeemer College received no response. The University of Sussex declined to comment on an ongoing legal case. However, senior academics at the university, speaking off-the-record given the pending litigation, said several principles were at play at one time.

Resisting a substantial fine at a time when university budgets are relentlessly pressured was not seen as the main motivation for the legal challenge, not least because if it fails, the university will likely pay more in legal fees than the total fine.

Rather, the fundamental issue of fairness seemed to at stake: academics felt it to be “deeply wrong” that Sussex could be fined a six-figure sum for a single document, when a near identical one had been in use at “dozens” of other universities. But underlying it all was the idea of whether anything the OfS was doing could really be said to be strengthening free speech, rather than just threatening it in a new guise.

Universities exist within a centuries-old principle of academic freedom. It should be simpler here than almost anywhere else to establish norms for free speech and debate. But whatever anyone makes of the rights and wrongs of religious freedom, or gender expression, the current rules and their application by the regulator seem fraught and confused.

The OfS seems to have been landed in a no-win situation. It is by its nature a bureaucratic organisation, a regulator whose initial purpose was monitoring student experience and quality of education. Now it has been left to enforce the ancient principles of academic freedom by interfering with academics and how they run their institutions. It is a fundamental paradox made all too clear by the politicised nature of its very first enforcement action.

Enforcing freedom by statute is a challenging task. In the short term, that will be a technical matter for the High Court, as to whether the OfS correctly carried out its duty under the law. In the longer term, it feels like the question will inevitably come back to government—is “freedom” on terms set out by the state and enforced by regulators really anything worthy of the name?