There’s a paragraph, early on in Liel Leibovitz’s life of Stan Lee, that pretty much causes the jaw to hit the floor and the eyeballs to pop out. It was late 1961 and comics were in the doldrums: the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s attack on the industry as damaging to children had led it to adopt a prudish Comics Code to avoid government regulation. Seriously considering quitting Atlas Comics (later called Marvel) for good, Lee hunkered down with the artist Jack Kirby and created the Fantastic Four. As Leibovitz ably describes, the Four were like nothing that had come before: superpowered, yes, but bickering and uncertain—polyvalent. They were morally and personally complex and relatable in ways that the old superheroes in whose shadow they were born were not.

The main axis of internal friction mirrored the friction between their creators. Ben Grimm, “The Thing,” was Kirby: saturnine, street-smart and brawny. Reed Richards, “Mr Fantastic,” was Lee: clever but irritating, all long words and big ideas.

But it was what came next, and how fast, that astonishes. When the Fantastic Four became an instant hit, Lee’s Atlas boss told them to write some more super-heroes: “the Hulk arrived in May 1962, followed, in August, by both Spider-Man and Thor. Iron Man debuted the following March, and by the time 1963, the grievous year of the Kennedy assassination, slouched to an end, Lee, almost always working with Kirby, had delivered Doctor Strange, the X-Men and the Avengers.”

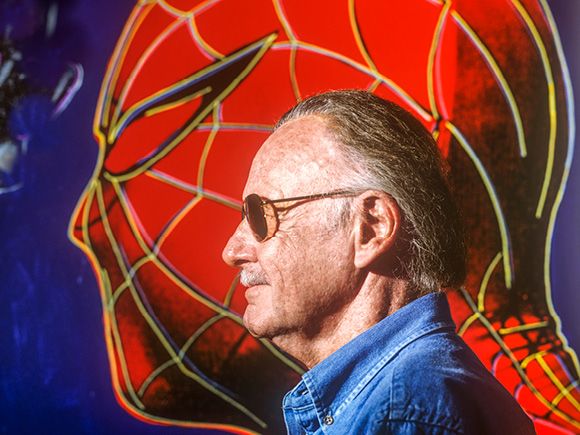

Those mere two years, then, gave us a constellation of characters and a fictional universe that has endured for seven decades, and by the end of the 1960s, “the Silver Surfer, the Black Panther, and the Guardians of the Galaxy had all joined the pantheon.” Since then the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) series of 23 films, beginning with Iron Man in 2008 and completed last year with Avengers: Endgame, has collectively grossed $22.5bn and brought the characters created by Lee, who died aged 95 in 2018, to a new global audience.

Back in the 1960s, Lee gave comics an idiom they had not possessed before. I don’t think it’s too much to say that 1962-3 was for comic books what Lyrical Ballads was for poetry. The Marvel and DC universes are almost certainly the most extensive pieces of continuous narrative in human history—which should commend them to the attention of anybody interested in culture.

That said, they’re still apt to be dismissed as kids’ stuff—even if the moral panic that used to surround them has more or less evaporated. For most of the time in which he was doing his best work, Lee got used to people wincing when he told them what he did. He told a story (“like many of Lee’s finest… probably apocryphal,” says Leibovitz) about mentioning to a gun salesman in the Catskills that he was a comic book editor. “Totally reprehensible,” the man replied. “You should go to jail for the crime you’re committing.”

“Relatively few individual comics have much to them, but each adds another layer of varnish to a mythos”

Even superhero creators sometimes have their doubts about men in tights. Alan Moore (co-creator of Watchmen) has more than once said words to the effect that “the mass devotion of middle-aged people to superhero figures might be a cultural indicator of intellectual and/or emotional arrest.” Warren Ellis, one of the best writers currently working in superhero comics, has called them “corporate-owned mythologies.” He didn’t mean it as a compliment, but mythologies is spot on. These comics play endless variations on essentially immortal characters—what another comics writer, Grant Morrison, called “Supergods” in his 2011 book of that title (US subtitle: “What masked vigilantes, miraculous mutants, and a sun-god from Smallville can teach us about being human.”) These comics trade in archetypes—often crude ones—and their literary effects are aggregational. Relatively few individual comics have much to them, but they add another layer of varnish to a mythos.

The resilience and adaptability of those myths, their symbolic breadth and their protean meanings, made them attractive repositories for broad identification and big ideas. Myths are, as Lévi-Strauss said about animals, “bonnes à penser.” Leibovitz rightly emphasises how fungible these characters are. He refers to Mark Millar’s mini-series Superman: Red Son, imagining a world where baby Supes landed in a collective farm in Soviet Ukraine rather than a wheatfield in Kansas. He might also have mentioned how well Neil Gaiman transposed Marvel’s pantheon to the Elizabethan era in Marvel 1602.

The human and self-doubting superheroes of Marvel’s Golden Age—it’s telling that among the technical innovations that distinguished Spider-Man was the extensive use of thought bubbles, “a feature rarely used in the action-oriented world of comic books at the time”—arrived in the midst of America’s tumultuous 1960s. They caught a wave. The Hulk, that oddest and most existentially troubled of comics characters, became a pin-up for students and was named in Esquire’s 1965 list of the most influential people on college campuses. The X-Men, likewise, were held to allegorise the civil rights struggle—with Professor Xavier standing in as a groovy, meliorist Martin Luther King and Magneto as the militant Malcolm X. And the Black Panther was the Black Panther before the Black Panthers were the Black Panthers.

As Leibovitz puts it: “Young Americans, seeking art forms that addressed the turmoil—social, political, emotional, moral—they were experiencing every day, did what they have always done in moments of upheaval and turned to the nation’s homegrown art forms. In the 1930s, that meant jazz and Hollywood movies; in the 1960s, attention shifted to rock ‘n’ roll and comics. The first was libidinal, bacchanalian, cathartic; the second was heady and loose, a sandbox of big but pliable ideas [my italics]. Both were, in the true tradition of indigenous American art, passionately dedicated to merry theft—of concepts, of backbeats, of aesthetics—and both inhaled, deeply, the fumes of influence, making them ideal instruments for processing anxieties in real time.”

The Jewishness of the early comics industry was memorably given imaginative life in Michael Chabon’s novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. It’s ever present in the story, from its economics, modelled on the piecework system of the garment industry in which Lee’s fabric-cutter father traded before the Depression wiped him out, to its sensibility, shaped by ideas of secret identity, difference and assimilation—as well the ever-present background of the Holocaust.

Leibovitz, whose book appears in a series called Jewish Lives, drills deeply into this. Born Stanley Lieber, Stan Lee was a graduate of the same Bronx high school that produced fellow comics artists Will -Eisner and Bob Kane (then Robert Kahn). Lee was a bookish child with a flair for showmanship. He wrote in his high-school yearbook that his goal was “to reach the top—and stay there.” He did—though he never wrote the Great American Novel to which he aspired. In 1939, aged 17, he joined Timely Publications (later Atlas), run by a relative, as an office-boy in the comics division—which then consisted of Joe Simon, Jack Kirby and Syd Shores. He went about the place playing an ocarina and, from time to time, sporting “a four-colour beanie with a propeller on the top.” He was irritatingly talkative (at school he’d been known as Gabby) but went out of his way to be ingratiating, had bright ideas, and was fast promoted.

Even his diction was New York Jewish to the syllable. Leibovitz retails a story of Lee having lunch alfresco in a fancy restaurant when a dollop of birdshit landed on his shoulder: “Lee looked heavenward, shook his fist, and yelled in mock outrage: ‘For the gentiles, you sing!’”

But it’s the Jewishness of his imagination more than his sense of humour that made a difference. Leibovitz borrows from the historian Garry Wills the idea that America’s Protestant soul is a contest between head and heart: elite, technocratic “modernism” on one side and tent-revival “fundamentalism” on the other. “Anyone writing comics in 1941 was toiling in the shadow of two colossal figures, Superman and Batman,” Leibovitz writes, identifying them as “not much more than the sum of their derring-do”: less human beings than the “embodiment of the two warring poles of American spiritual life.” Batman was a “wealthy and privileged Brahmin with no special powers who used his endless resources and superior intelligence to deliver a vastly improved version of local government.” Superman, on the other hand, is “a creature of the fundamentalist imagination”—from his “vaguely Hebrew name Kal-El, meaning either ‘voice of God’ or ‘the entirety of God’” to his Mosaic origin story. Superman, in sum, is Jesus with X-ray vision and disco tits.

Lee’s creations, Leibovitz argues, internalised those conflicts. And they contextualised them in a network of interdependent human relationships: “Rather than champion this pole or that of a dichotomy that was too extreme and inhospitable for actual human beings, [Lee and Kirby] created a world in which the best human beings could hope for was not deliverance by some god in tights but the hard, communal work that makes life just a little bit better.”

Within the Fantastic Four, for instance, Reed Richards is the modernist, and Ben Grimm is the fundamentalist. The Thing is essentially a golem, and Reed Richards is possessed by the dybbuk, which gives him his lust for scientific knowledge. In more compressed form, the Bruce Banner/Hulk dyad gives us golem and dybbuk in one person. Spider-Man, Leibovitz goes on to argue—a little less persuasively but no less ingeniously—draws on the myth of Cain. The Fantastic Four’s first confrontation with the godlike Galactus and his herald, the Silver Surfer, draws on a plot archetype from the Book of Numbers and pivots, he says, on a series of essentially Talmudic exchanges about the nature and dignity of man in the divine scheme.

“Lee created a world in which the best human beings could hope for was not deliverance by some god in tights, but the hard, communal work that makes life a little better”

At a less arcane level, even one of Stan Lee’s earliest comics grappled with an enduring theme of these stories. As Stan famously put it in Spider-Man (quoting or paraphrasing, Leibovitz tells us, Jesus Christ, Winston Churchill and FDR inter alia): “With great power there must also come—great responsibility!” In a 1941 strip called Jack Frost, written when Lee was just 19, the titular superhero rescues a damsel in distress—but then refuses to go back into a burning building to rescue the villain. The villain burns to death. The police try to arrest him for murder, and Jack vanishes back to the North Pole in a fit of pique. Crudely, what would it mean to have superpowered characters wandering about the place dispensing justice as they see fit outside the law? It’s a question to which superhero comics return incessantly and which, in the 2006 Civil War storyline, came to animate the whole of the Marvel Universe.

What Leibovitz’s emphasis slightly sidesteps is the way that, while the Marvel Universe may indeed have had a Jewish cast of mind, it was on the surface almost insanely syncretic. It has been an omnivorous and indiscriminate plunderer of myths and myth-fragments. The Norse and Greco-Roman pantheons rub along happily with Aztec and Polynesian deities and the demons of early-modern Christian Pandaemonium—as do gods worshipped by alien races and any number of other omnipotent and near-omnipotent beings such as Galactus, the Beyonder, Thanos and so on. Miracles are everyday occurrences in Marvel. The resurrection of the dead is a cinch. The one thing that looks impossible here is monotheism.

Or maybe not. As Leibovitz says more than once, Lee’s greatest creation may have been himself. From the late 1960s onwards, Lee was as much impresario as creator: touring college campuses, giving TV and magazine interviews, and speechifying from the soap-box slot in his Bullpen Bulletins. He dreamed up the fan-club gimmickry, the No-Prizes (empty envelopes mailed to fans who wrote in pointing out continuity errors), and developed Marvel itself as a brand with Lee at the centre of it. And in old age he parlayed his own persona into a series of avuncular cameos in the Marvel Cinematic Universe—which became so predictable that the spoofily self-referential DC animation Teen Titans Go! To The Movies includes a cartoon Stan Lee, voiced by the man himself, appearing clinging to the windscreen of a speeding golf cart: “I’m back! I don’t care if it’s a DC movie! I love cameos!”

Like many artists, Lee had a ruthless streak. A baleful subplot of this book concerns the treatment of Jack Kirby, who—though he semi-reluctantly returned to work for and with Lee over the years—went to his grave convinced that Lee had at worst sold him out and at best failed to fight his corner when it came to a fair deal over his creations. The sorry saga of intellectual property in superhero comics is touched on by Leibovitz but not explored in detail.

Anyway, it worked out okay for Stan Lee. He never got the slice of his creations he by rights deserved—but he did much better out of them than most of his predecessors and contemporaries. He drew a million-dollar annual salary as chairman emeritus when he stepped down in 1996 as Marvel’s publisher. And he stayed on board as they moved, from the noughties on, from being at the margins to the centre of American popular culture.

The cleverness of the MCU films’ adoption of its source material was in following Lee’s lead. Fans were put at the heart of their production: the in-jokes and Easter eggs, the attention to the comics canon, the tapestry of crossover appearances, and the balance between jokiness and operatic emotion helped to preserve the winning feel of the comics. They’ve even got noticeably more right-on between 2008’s Iron Man and more recent outings for the Black Panther and female superhero Captain Marvel. With great power…

Leibovitz, it should be said, can sometimes be charged with over-exuberance. He talks about the “immense depths” of the Fantastic Four, likens Stan Lee to Bob Dylan (“another gnomic Jewish artist… his comic books, like Dylan’s songs, have become vast cultural canvases onto which anyone interested in the art form can paint her or his own interpretations”), and Kirby to “a latter-day Goya capturing the vicissitudes and torments of the suffering human soul.” Of artist Steve Ditko’s full-face mask design for Spider-Man, he writes: “to look at Spider-Man’s blank eyes was to feel not only his pain and insecurity but your own as well, like an abyss you stare into long enough only to realise that it, too, is staring into you.”

Your mileage, as they say, may vary—but better, I think, to over-interpret than take the traditional route of refusing to interpret at all. Make mine Marvel.

Stan Lee: A Life in Comics by Liel Leibovitz (Yale University Press, £16.99)