His office is nestled deep within John Soane’s revered neoclassical temple. There is a vast old desk of the sort that you’d expect to find a mandarin or even a general settled behind. Up on the walls, in gilded gold frames, are old-fashioned paintings of even more old-fashioned buildings.

In the corner, there’s a flip chart, with a bit of econo-waffle scribbled on it—“Phillips Curve, P, U*,” which stirs dim memories of dull lectures about inflation and unemployment. But then another scribble catches the eye: Works, Feels, LOLs. What on Earth, I ask Andy Haldane, does that mean? It is, he relays, the three ways you “get purchase” in the public discourse—doing things, stirring emotions or making people laugh. Says who? “Grayson Perry.”

And what had a transvestite potter got to do with his work at the Bank? Well, it transpired, Haldane had very recently roped Perry in for an event with Bank staff, partly to talk about communication, but partly simply because he thought the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street would benefit from the Turner Prize-winning artist’s “lens on the world.” And not only Perry. “Last week, we had [the Pennine poet] Simon Armitage; next week we have Evelyn Glennie, the percussionist, coming in.” Why? Haldane wants Bank staffers to tap their “wellspring of creativity,” which he believes is always best sparked in what, borrowing a phrase from Armitage, he calls, “the crashing of cultures… the crumple zone.”

This sounds even more far-out than Howard Reed’s call to smash up the neoclassical foundations of economics, and use the other social sciences to rebuild it. But there is nothing in the appearance of this svelte middle-aged man, nor in his measured, mildly-Yorkshire inflected tones to suggest an intellectual revolutionary. And his CV—28 straight years working his way up at the Bank, since taking his Master’s—suggests precisely the opposite. Indeed, Bank staff speak of an approachable, but otherwise conventional Bank sort, “lives in the Surrey commuter belt, kids at private school,” says one.

But rifle through a few of his speeches, and you see that he never stops looking for intellectual inspiration in places which are, on the face of it, miles away from his discipline. “I have,” he says, “been begging, borrowing and stealing ideas over the last 15 years, to try and make sense of the world.” Particularly after Lehman Brothers fell over in 2008, he might have felt a special responsibility to do that because he was tasked with assessing “systemic risk” at the time when, as the Queen has put it, “nobody saw it coming.” But there is nothing defensive about the eclecticism; it just seems to be how he is.

His calm air almost abandons him as he fizzes with enthusiasm about an American econometrician who has opened up a “window on the soul,” in a manner which would help to predict recessions, through a “semantic analysis” of the sorts of songs people are downloading. In lecturing on the finance system, he cites epidemiologists, draws parallels between investment bubbles and viruses. He has even co-written a paper in Nature with the evolutionary biologist Robert May; the last one he wrote was with “a plasma physicist.” And at moments he really does seem to think, like Reed, that mainstream economics has got it all wrong by obsessing about markets settling in an orderly balance, when in truth “there is no state of rest, and often no… equilibrium; is the world, or our social system, ever at rest?”

"Haldane hopes to tap the wellspring of creativity in Bank staffers through 'The crashing of cultures... in the crumple zone'"There is, he says, “no such thing as a perfect model.” Economists need a “healthy degree of humility” about what they don’t know, and be prepared to switch to a different “box of tricks” when the world surprises them. Indeed, for several years now he has been recruiting more historians and other social scientists in the hope they will challenge the Bank’s many economists.

Unlike some at the Bank, including Mark Carney, his Canadian boss, there is nothing of the flashy financier about him. And unlike not only Carney but also Ben Broadbent and a couple of others on the Bank’s Financial Policy Committee he has never worked at Goldman Sachs.

In terms of ethos, he is more in the mould of the scholar-turned-Governor, Mervyn King, with whom he shares an obsessive interest in cricket. Like King, he self-describes as “a public servant” first and foremost, and like a good civil servant he suddenly gets discreet to the point of dull when talking about his colleagues and the institution in which he works.

But whereas King sometimes gave the impression he would rather be in the ivory tower, Haldane would rather be anywhere else. He gets out of the office as often as he can, not to retreat on to university campuses, but to tour the less glamorous corners of England. A couple of weeks before we met he had been in Ashington in the northeast, which has had “a tough time since the last pit closed in ‘86”; “last week I was in Blackpool… On Monday, I’ll be in Stoke.”

When he gets to these places, the Bank’s long-established regional outreach offices put together roundtables and meetings for him. And, deliberately, he tries to resist the “natural pull” to engage with the bosses of success stories, and to engage with the staff and the managers for the “long tail of companies” that have “stood still.” When Britain is in the grip of stagnant productivity, there is an analytical justification for this, and Haldane assures me that when you’ve got to grips with prosaic failures of so many of these firms to take “the structured approach to internal supply chains” which successful companies have been taking for years, then “there is really no productivity puzzle at all.”

Read more: The case for a new economics

But it’s pretty obvious, too, that Haldane also feels an obligation—moral or political—to, as he puts it, “listen much harder to those with quieter voices.” His background, perhaps, gives a bit of a clue as to why he devotes quite so much of a packed diary to what “the anthropologists call… ‘deep hanging out.’”

Schooled at the local comprehensive, and then heading for university at Sheffield rather than Oxbridge, LSE or any other conveyor belt for establishment economists, Haldane was raised in Guiseley on the edges of Leeds.

His dad, a professional trumpeter, always had work, but that wasn’t true of the fathers of many of the kids in his class in the early 1980s. He saw, he said, “tragic consequences” of unemployment, and “people laid low, not just financially but psychologically.” It was, he says, this “very practical perspective” that “drew me into wanting to understand how the economy worked and wanting to do something about it.” He remains, says a colleague, “seriously interested in ‘shit-life syndrome.’” He speaks with horror at what has happened to the American Rustbelt, where you see a “doom loop,” “a poverty of optimism… which means people stop ‘investing’ in themselves” and maybe even “their children”; the upshot is “alcohol and opioid abuse, and death rates that are picking up.”

He seems hopeful, however, that run-down Britain is not doomed to enter the same death-spiral. He has no truck with those economists who think the solution for the “left-behinds” is to move: the notion of “get on your bike” has “always been fanciful,” because “people want roots.” Instead, he thinks it falls to public policy to salvage struggling towns, and seems more sanguine than many about the chances of success, particularly because “pretty much everyone” now “accepts the need for industrial strategy.” And on the specifics of what that has to involve, Theresa May’s government’s green paper at least says “all the right things.” Of course there are questions about “execution,” but barring “distraction” he seems to think a great deal can be done.

The most likely distraction is, of course, Brexit, about which most economists are extremely grim. It’s not the kind of thing you can ask an official on the record, but I’d be pretty sure Haldane voted “Remain.” But he sounds less despairing about the outcome than most, not least because he was always convinced there were so many towns that were in sore need of “some TLC… with or without Brexit.”

Indeed, not in our conversation, but in past public statements he has contradicted his boss, who played a prominent part in the campaign and its aftermath, and cautioned against relying on a cheaper pound to ride to the rescue. Haldane argued instead that the post-referendum fall in sterling will do something for competitiveness. He is extremely warm about “Mark” when we meet, but he must have known what he was doing then because, as one Bank staffer puts it, “Mark doesn’t like to be contradicted.”

Haldane at least understands the sentiment of May’s “citizens of nowhere” speech. It is, he says, because people hanker for “the security of having somewhere called home,” that “the majority of people live within 10 miles of where they were born.” Certainly, his home town still keeps him rooted. While most of liberal London was stunned by the referendum, Haldane says “it was there if you listened to the right people.” Who was that? When he went “back to Guiseley, and down the pub with old mates. And they asked questions, and they were good questions—‘we thought the EU’s institutions were crap’? (well, yeah, maybe they have been a bit crap); ‘we thought that all the politicians had been saying they didn’t work for 40 years?’ (well, yeah), and then ‘so why is it we’re all meant to vote Remain?’”

When he was expounding on something called “narrative” social science, I wasn’t sure I understood, but as he told that story I got what he meant. It is, I concluded, just that the stories we tell each other affect the way we think and act. You can, Haldane says as I’m leaving, “call it irrational if you like; I call it human.”

The new Court of the Bank:

Billy Bragg

The Jeremy Corbyn-supporting singer- songwriter, who performed gigs to raise money for striking miners in the 1980s, warned the Bank about the “increasing alienation of ordinary citizens.”

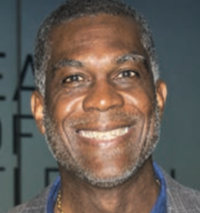

Michael Holding

The West Indies fast bowler, above, who was nicknamed “Whispering Death,” spoke at Threadneedle Street in 2016. No word on whether he was asked to turn out for the Bank of England XI at their annual summer party cricket match.

Grayson Perry

The Turner Prize-winning potter, below, has also written about how toxic masculinity contributed to the financial crisis.

Copyright: MAJA SMIEJKOWSKA/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK, RICHARD YOUNG/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK, RAY TANG/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK