A leading neo-conservative, Irving Kristol once defined neocons as “liberals who have been mugged by reality.” Similarly, I fear that those today who speak of the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union as a chance for Britain to become a global trader again will be mugged by economic reality. Given the recent performance of the British economy, where prices are rising and wages are stagnating, that mugging may already be under way.

Globalisation has mugged far larger countries when they mistook economic integration for shackles, and tried to make it on their own down lonely pathways of trade. Brazil and much of the rest of South America stepped back from globalisation, including by limiting trade and investment with the United States. These nations deprived themselves of stable growth. India infamously tore up its trade relations with the west for decades in pursuit of autonomy and self-sufficiency, attaining neither. China only leapt forward when it opened up, albeit partially.

The UK was perhaps especially prone to mistaking useful economic ties for chains, because it had a longstanding ambivalence about its EU membership. One codified aspect of the European project has always been the idea of an “ever closer union,” which was never an easy sell for an island nation. The best anybody was going to do was the UK being sort of in, sort of out—and so it was, for as long as it remained inside the single market, but outside the Schengen area and the single currency, with a bespoke rebate to boot. It probably ceased to be sustainable after a majority of the member states bound their fortunes more tightly together in the euro area. And it certainly ceased to be sustainable after many in Britain, and particularly England, began to take the same sort of root-of-all-evil view of Brussels that many Americans have taken of Washington.

NEW: listen to Adam Posen discuss the post-Brexit economy on the Prospect podcast, Headspace!

The sad result of the referendum is that the UK has lost its comfortably ambivalent status within the EU; even Remainers who hope Britain may yet reconsider or rejoin the EU should not presume the country will get back any of the same opt-outs and rebates as before, unless it is willing to spend years rebuilding lost trust. And leaving that state of political ambivalence has a very simple economic implication: the UK economy is suffering “a negative supply shock.” A negative supply shock means you are reducing the productive capacity of your economy, or the ability of your economy to purchase things for the same amount of money as you used to. Now, we can debate about how big is the harm, which industries get hit, what happens in the end after the UK adjusts, but there is no serious disputing that a shock of this sort will be the result of withdrawal. Why? Because withdrawal from the EU will put up trade barriers.Shocking truth

In pure economic theory, the UK could do away with all of its tariffs, not only those with the EU, but with the entire world, and leave the UK consumer much better off. One, decidedly fringe, libertarian faction of Brexiteers fondly entertains this as a vision of the future. It is a delusion. Unilaterally opening all UK markets to the whole world would, in reality, impose substantial dislocation and disruption on thousands of businesses and millions of workers. In any event, no government—and certainly no nationalist, Brexit government—is going to stand idly by while domestic industries are hammered by foreign competition at home, especially when there are no reciprocal opportunities for exports opening up. Additional trade barriers are inescapable, and trade barriers are, fundamentally, bad for your economy. There is no disputing that this is a negative supply shock, and—furthermore—it is a negative shock that will ruin Britain’s competitiveness, very specifically, with its largest trading partner. The heightened barriers could apply on up to half of British global commerce. The market access that will be lost cannot and will not be replaced, even in a generation, due to the “gravity” of trade flows. It is one of the few things in economics we can talk about with the same sort of confidence as natural scientists—as a fact of life. In physics, the more massive and nearer a body is, the greater the gravitational pull it exerts. In commerce, gravity means that you trade far more with countries you are contiguous with or which are nearby, than you do with countries that are far away. This pattern of trade is not only logical—a consequence of the costs and delays inherent in long-distance trade, and of the networks and habits that develop through history—but is also borne out by all studies of trade patterns. No matter how much there has been a special relationship, be it with the US or the Commonwealth, no matter how much the UK may want to be a global exporter, the fact is that the UK has more than twice as much trade and investment with the EU than it does with the US, let alone with anyone else in the rest of the world. The UK has exported more to Ireland than China in nine of the past ten years, despite China’s economy being nearly 40 times the size of Ireland’s. None of the other major emerging markets, Brazil, India or Russia, are in the top twenty markets for UK exports. So even if we were to negotiate several new global trade deals with rising economies, it would not offset the shock of leaving the EU, and could not do anything at all in the short term. In theory, a UK-US trade deal has slightly more potential. There is no question that Donald Trump has the authority to move the UK to the head of the queue if he chooses to. And it would not entirely surprise me if he did, because American culture has some affinity with watching Downton Abbey and Dunkirk, and Britons are thought of as rich white people by Trump voters. But if he did, would Congress ratify his deal? After all, it is hardly in the US strategic interest to annoy the EU, the largest economic bloc in the world, especially when the US is already alienating Canada and Mexico by aggressively reopening the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta). Besides, even if a Trump-backed Anglophone trade deal could be approved, to what end? The Trump administration approach towards Nafta, and all the trade officials’ statements make clear that his real priority is to tilt bilateral trade balances in the US’s favour. Even if he did give the UK a trade deal, it would be a bullying deal which made it certain that the UK would end up buying more in the way of extra US imports than it would be able to sell in additional exports. The overall negative supply shock would remain, and Britain’s ability to succeed in trade would not be improved. New trade deals are not going to make up for the disruption to trade with the continent. The news gets worse for the UK economy when we consider the impact of Brexit on cross-border investment. Because the UK had this special status as a less-regulated, low tax, English-speaking, rule of law sort of a place, that was nonetheless still in the EU, it used to attract investment as a welcoming platform from which to trade with the wider EU. All the more so as many non- European business people liked living in London. Now this investment is going to drain away, not to zero, but it will gradually decrease. Toyota, Nissan and Ford, for example, all have disproportionate amounts of their European car production in the UK. All have indicated that they will not expand those plants, for example, when the UK loses full market access, and their production will likely decline.Counting costs

It bears repeating that there is a distinction between a limited and thus feasible trade deal for the UK with the EU, and full membership in the European single market. A simple trade deal would normally start by reducing the rate of tariffs charged on some goods and perhaps a few services. The single market, however, covers all those things that are not simply the price of goods off the boat. It is whether your vehicle meets safety standards, whether your chemicals or food additives have been recognised, whether you fit standard sizes of various objects, whether your accountants are accredited, or whether your university degree is recognised in other countries. These regulations cut both ways. They are partially inefficient restraints on business, protecting incumbent companies and guilds from competition. At the same time they are also partially economically beneficial, because they set the ground rules that facilitate a large and integrated market. In any given industry, the European standards will display more or less of these two attributes. But since the UK is primarily an exporter of higher-end products and especially of business, financial, media and education services, there can be no escaping the need for agreed rules and standards. So it loses a lot by being—as Theresa May has proposed it should be—outside of the single market, even if it manages to get a trade deal. Of course, one can say, “Ah, but Brexit is about the long term. The UK economy will adjust, and over the long term, we will be better off.” But how? Beyond fanciful hopes of gravity-defying trade deals beyond Europe, the case for being bullish here comes down to sparing the UK from the supposed growth-sapping “costs of Europe.” Five such costs get talked about. There is overregulation of EU labour markets. There is heavy-handed regulation from Brussels in other things. There are big bills for European-style welfare states. There is demographic decline. And there are problems associated with euro membership. Now, on that list, four of those five do not apply to the UK, even if it stayed a member of the EU. The UK has looser labour market regulations than anyone else in the EU, and—even while complying with those strictures that Europe does require—its labour markets remain flexible by world standards. The EU has not prevented the UK having a smaller welfare state than comparably wealthy states in western Europe. Demographically, the UK has actually been a beneficiary of membership of the expanded EU, because people from Poland, France, Portugal and Romania have come and helped balance out the ageing of British society. And the UK was, of course, never a member of the single currency.Double-dip: Real wage growth for the continually-employed

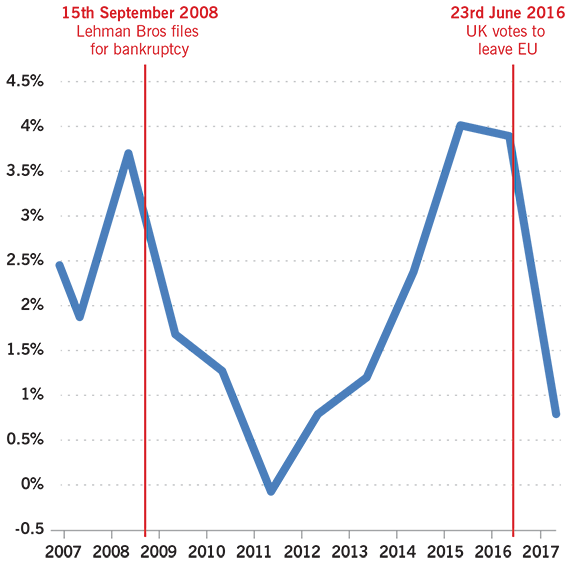

Reality check

Assuming Brexit goes ahead as May plans, the UK is simply going to have to cope with this negative supply shock. In order to adjust, the British economy will have to endure some mix of higher inflation, lower purchasing power, declining terms of trade, and a weaker pound for several years. This painful adjustment process has in fact already begun, as was seen when the Bank of England felt it necessary to raise interest rates in November, despite there being little reason to do so in terms of domestic conditions. Mark Carney, the Bank’s Governor, made clear that the impact of Brexit brought productivity and currency concerns to the fore. More fundamentally, the UK economy will have to absorb this shock at a time when it is already suffering from a staggering decline in productivity growth relative to other western economies. This other reality inherently makes any Chancellor’s Budget arithmetic much more difficult, (see Diane Coyle, p26.) Even more importantly, near-zero productivity growth means near-zero real wage growth. There is no reason to expect that workers will be protected from the pain of inflation. Furthermore, the UK has accumulated through both the boom and the bust a set of large imbalances. It has ongoing budget deficits, large trade deficits, an over-concentration of activity in the financial sector, and then—in geographical terms—an over-concentration in the southeast as well. Over the last few years, even after the Brexit vote, there has been a further growth of consumer borrowing while corporate investment has gone negative and trade has gone the wrong way. Overall, the British economy already had a painful adjustment coming, and now that process will be compounded since the UK has resolved to pull itself out of economies of scale and curtail easy access to its biggest markets. Do the mental exercise. If this were Britain in the post-war Bretton Woods period, or during its time in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism circa 1992, and we were seeing this same mix of unbalanced macroeconomic indicators, we would predict a crash in the pound. The peg would be doomed. Thankfully, the UK today does not have a fixed exchange rate. But if you do that exercise, it reminds us of just how unsustainable the current British economic path is. The pound has to decline further. Like Britain as a whole, it has further to go in being mugged by reality. Stable prices and exchange rates are going to have to give. No one should fantasise that a depreciation will lead to prosperity, however, any more than repeated devaluations delivered sustained growth to the UK (or to Italy) in the 1960s and 1970s. At a time when benefits for the poor are frozen and—in the last few months—wage growth has ground to a halt, even relatively modest inflation is going to hurt. And the most obvious direct cost of imposing tariffs on imports from the EU, of declining terms of trade, is a sharp decline in British consumers’ purchasing power. A surprising recent economic phenomenon makes the challenge from globalisation to a Britain outside the EU even greater. We have seen the occurrence in recent years of currencies declining in advanced economies, while the trade gap fails to change appreciably. Usually a falling currency is thought to be a direct mechanism of adjustment for a country that is suffering from declining terms of trade. So, in the case of the UK, after the pound falls, Brits used to find they could afford fewer German cars or Italian holidays and cut back on those products for cheaper domestic substitutes, while at the same time British exporters found their wares were cheaper in euros or dollars, and thus sold more. But that textbook adjustment is not working today. In fact, it hasn’t worked in Britain for some years. There was a similar pattern at the start of the crisis where the trade-weighted pound also declined sharply—by roughly 25 per cent over the course of 2009—but the trade gap failed to close very much at all. One factor is that the UK is towards the upper end in global supply chains. That means whether it is cars or financial services of certain kinds, production requires a bunch of imported inputs, whether of people or car parts, before the end product can be exported. The net gain you get from currency depreciation is limited. A similar logic is at work in Japan, where the decline in the value of the yen in recent years has not had as big an impact on the trade balance as economists initially expected. A second point is that the crisis meted out a structural hit, targeted on Britain’s bloated financial services industry—reducing it from about 15 per cent of UK GDP at its height, to somewhere in the region of 10 to 12 per cent. That is a large and sudden shrinkage in a major economy, reflecting the wider economics of the crisis and more particular failings of the City. The damage to the British financial sector is now set to be multiplied by the shift of some of those financial services to Ireland, Germany, the US or wherever, once the single market is exited (see Nicolas Véron, p30). These are real lasting setbacks to British service exports for which exchange rates alone cannot compensate—at best, a persistently weaker pound will, over time, lead to a reallocation of workers and investment to industries that compete internationally on price, rather than quality. That sounds like a step backwards. Whatever the reason why depreciation has ceased to work to improve trade balances as it used to, it leaves the UK an unbalanced economy facing a self-inflicted supply shock with one fewer means of adjustment to the new reality.Defying gravity

Amid the daunting reality of international commerce outside the EU and low productivity growth, it is plain that Brexit is only going to succeed economically for the British people if the country were to somehow leap beyond the reach of economic gravity, and replace much of its trade with the EU with new markets. There is no obvious precedent, however, for any large nation successfully defying gravity, and reordering its trade on a whim, let alone doing it so quickly."At least the original Thatcherites could point to some plausible mechanisms for imposing new discipline"At best, a long and painful process of adjustment is required to reorient to new markets, new industries, and new relationships. In the decades after 1989, the old Eastern European countries did achieve this—but these iron curtain countries had the option of competing as low-wage economies during the generation-long adjustment period, much to the annoyance of Brexiteers. There is no reason to believe that Britain, a country where wages already disappoint domestically but remain high by world standards, will be able to pull off the same trick. More importantly, while Eastern Europe could forge a new economic accord with the west, there is absolutely no reason at all to believe that the rest of the world will alter its patterns of trade and investment in reaction to the efforts and aspirations of a Britain that has, for whatever reason, resolved to go it alone. Believing such a shift will happen requires a faith that recalls Margaret Thatcher’s proclamations of TINA, that desired change must come simply because There Is No Alternative. Her disinflationary policies did not ultimately succeed in transforming the UK economy: inflation and trade deficits bounced back with the economy in the late 1980s. Despite Thatcher’s insistence on TINA, it transpired that the British economy did not readily adjust to bullying. But for its devotees, Brexit is likewise bound to succeed today because it must. What else, however, does one have to believe to sustain that faith? Brexit would have to cast some very special spell on all British businesses, to offset the damage done by rising trade barriers, and the flight of investment and workers from abroad. Thatcher would surely be appalled, and protest that such magical thinking involved standing TINA on her head. For all the social harm unleashed by the Iron Lady and TINA, at least the original Thatcherites could point to some plausible mechanisms for imposing new discipline—like hard money and fiscal austerity, as well as the resulting strong pound, which would force painful shake-outs on workers and old industries. The Brexiteers’ TINA is, instead, somehow meant to force transformation on an economy beset by rising inflation, and in industries that are increasingly sheltered behind trade barriers, starting with tariffs re-imposed on EU goods. Brexit is not going to make Britain into a wonderful capitalist exemplar, let alone a global trader, like Hong Kong was in the 1970s. Brexit is going to make today’s Britain more like Britain was in the 1970s. Ultimately, it will produce lasting economic harm to British citizens, because market economics works and global integration has benefits. The costs of some overregulation imposed by Brussels in some industries are nothing to compare with the self-imposed costs of a trading nation running away from globalisation. That’s reality. This article has been amended to clarify the relative size of Britain’s trade with Ireland as compared with the BRIC economies.