Facing a clamour of demands for a vision of post-Brexit Britain and its place in the world, the beleaguered prime minister might find instruction in her favoured period of England’s past. When asked by the Observer 13 years ago which historical figure she most identified with, Theresa May chose the indomitable Tudor queen Elizabeth I, a woman “who knew her own mind and achieved in a male environment.” More recently, the press have been quick to invoke Shakespearean ideas of a sceptered isle and the defeat of the Spanish Armada, and more diffuse golden-age mythologies, all of which will rouse cynicism in suspicious minds. But the late Tudor age really does have deeper lessons to teach us about the dark arts of Brexit.

Elizabeth I did, after all, come to the throne facing her own Brexit moment. In reconstituting the Protestant Church of England, she reinstated the break with Rome and papal authority that her father Henry VIII had initiated earlier in the 16th century, but which her sister Mary had bloodily sought to reverse. This move rendered her heretical for the Catholic bulk of Europe. At a stroke, England was once again severed from the community of European Christendom.

New strategies were needed. In 21st-century Britain, the imperative is somehow to open up new markets, to boost exports; in 16th-century England, the same drive was given added urgency by a seething conflict with Spain, the dominant Catholic power and the standard-bearer for an aggressive Christian imperialism. By the 1580s a creeping embargo was initiated to cut off England’s continental trading partners, generate internal dissent and -governmental collapse. Elizabeth needed new allies, and fast.

The way all this played out seems remarkably prescient. It suggests five Elizabethan lessons for Brexit:

I: Division in government doesn’t end well

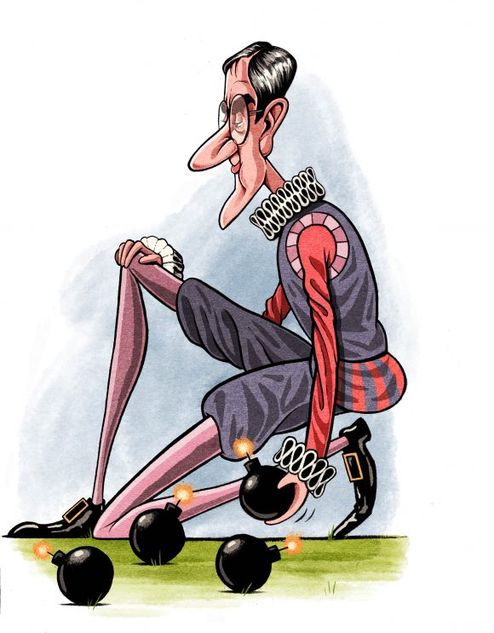

The cabinet and the wider Conservative Party are of course currently deeply divided over the nature of Britain’s future relationship with Europe, a split which was—until he flounced out of the Foreign Office—focused on the opposition between prime Brexiteer Boris Johnson, and the Chancellor Philip Hammond, a cautious remainer.

If it is any comfort to May, the late-16th century Privy Council was similarly split over England’s role in the world. The queen was often forced to arbitrate between two groups. The first advocated getting aggressively stuck into Europe, clustered around the charismatic and ambitious royal favourite Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. The second sought to make the most of their isolation while preserving royal funds, promoting peace and cordial diplomatic and commercial relations, focused on Elizabeth’s Principal Secretary Robert Cecil.

One can argue the toss about whether the Brexiteers are more in the tradition of the tub-thumping belligerents or the isolationists, but another parallel is harder to miss. At times, this division completely paralysed the business of government.

Today’s warring factions might reflect on how it all ended: Cecil triumphed. Essex followed a disastrous misadventure in Ireland—whose handling was a running sore for London then, just as it is amid the Brexit discussions today—with a failed coup against the queen, and he was beheaded at the Tower of London in February 1601.

II: Don’t expect too much from your new allies

Facing diplomatic isolation from mainland Europe and a freeze on trade—the 16th-century equivalent of crashing out of the continent on WTO terms, perhaps—the English crown had little choice but to cultivate new allies beyond the traditional realms of Catholic Christendom. By the end of her reign, Elizabeth had made overtures to Muslim Morocco, Ethiopia, the Ottoman Empire, Persia, India, Java and Aceh, to Orthodox Christian Russia, even to China. She was doing “Global Britain” before Britain even properly existed.

"Elizabeth was accused of breaking trust with 'old allies and friends'"Despatching a series of merchant-ambassadors with elaborately crafted letters, Elizabeth offered flattery, asked for friendship and for favourable trading conditions, and darkly hinted at the global ambitions of the pope, Spain and Roman Catholicism.

The strongest connections were those established with King Mulay al-Mansur of Morocco and the Ottoman Sultan Murad III. Elizabeth had great hopes that both would help thwart Spanish designs on England by attacking Spain and its possessions in the Mediterranean. She also expected a rapid expansion in English exports and intended to use the Ottomans as a springboard to Indonesia and the spice trade. More than that, an alliance with the Ottomans offered small, marginal England the chance to imagine itself holding court with the global powers of the age.

Despite such potential gains, in pure PR terms this was a disaster—a lesson Liam Fox might reflect upon as he pursues shiny post-Brexit trade deals outside the EU. English trade remained resolutely dependent on Europe, and her contemporaries lamented Elizabeth’s resolve to breach trust with all her “old allies and friends” in favour of “professed enemies to Christ.”

English polemicists decried the influx of cheap foreign goods and their destabilising effect on a balance of trade and national character. The English, they lamented, had fallen under the spell of novelty. William Harrison lambasted the “fantastical folly of our nation” for their keenness to dress in “the Turkish manner,” in “Morisco gowns [and] Barbarian sleeves,” and he also lamented a recent fashion for that unseemly Turkish invention, “the moustachio.” Others deplored the deluge of “foreign” trinkets—mainly jewellery, metalwork, ceramics, fine fabrics.

Diplomatically these “new confederates” promised much but delivered little. English ambassadors were routinely frustrated in their attempts to cajole the Ottomans and the Moroccans into conflict with Spain. The parsimonious Elizabeth can’t have enjoyed the constant demands for presents. But the brutal truth was that a newly lonely England had become the supplicant: the new globalism it was initiating came at a cost.

III. Selling weapons doesn’t endear you to the neighbours

One thing the English could—and still can—produce in large quantities was guns. Technological advances and mineral wealth meant that by the late 16th century, cheap cast-iron English cannon and shot drove a thriving trade in materials of war. Here was something the Ottomans badly needed, following a sustained and draining conflict with Persia. There was just one problem. Although Elizabeth was a heretic, she was still Christian, and expected to abide by Christian rules. One of those—enforced through papal decree—was that no Christian could trade in armaments with the “infidel.”

The English response was to go rogue. They were prepared to sell anything to anyone. Enterprising English merchants, often funded by senior figures in the Tudor regime, were exporting tin and lead to the Ottomans, and armaments, metals, saltpetre and gunpowder to Russia, despite the protests of many European monarchs and a succession of Holy Roman Emperors. One free-wheeling entrepreneur even exported 23 English-made cannons to Spain as Anglo-Spanish hostilities simmered.

Despite internal opposition and laws passed against the export of English guns—Walter Raleigh declared them too important to fall into foreigners’ hands—they were exported in large quantities as England responded to its exclusion from Europe by becoming the arms dealer of the Renaissance world. Observers condemned a “hateful and pernicious” trade, and came to see English gun-runners as “the troublers of all Christendom.” When confronted with the charge, Elizabeth simply denied everything, protesting the English would never sell arms to non-Christians, and insisting her only motives were peaceful and legitimate commerce, and the safety of her citizens.

For some, the world opened up by Britain’s EU exit is a place of similar opportunities. The new Department for International Trade has taken charge of efforts to promote British arms in a bid to use their sale to oil the wheels of post-Brexit trade. Earlier this year Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, deeply implicated in his country’s bombing and blockade in Yemen, made a state visit to Britain to conclude the terms of a £100m aid deal and negotiate the purchase of 48 British-made Typhoon fighters.

"The English were prepared to sell anything to anyone... England became the arms dealer of the Renaissance world"Billions in arms sales have subsequently been agreed, including to such places as Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, the UAE, Venezuela and China, hardly beacons of liberality. Little wonder a representative from BAE Systems recently pointed out that, for them, Brexit was “no big deal.”

No doubt the UK spies an opportunity to become a world leader in an increasingly rule-less world. In an uncanny echo of her idol Elizabeth I, May justified her recent arrangements with Saudi Arabia by arguing that they were in the national interest and would “keep people on the streets of Britain safe.”

IV: The promise of China is illusory

The single greatest prize of post-EU international relations for May and the Brexiteers, as for Elizabeth I, is China. Some are still amazed that it has become the world’s biggest economy on some measures, but the Elizabethans would see this as nothing new: in the late-16th-century China was also the preeminent global power.

Back then it represented an unparalleled mercantile opportunity, a long-established civilisation that produced sublime goods avidly collected in the English court.

New cartographic technologies convinced the queen and her courtiers that China was closer than anyone had ever imagined—not on the other side of the world, but a short journey over the top of the globe, through unmapped Arctic regions: “not so far remote” wrote Elizabeth in 1602, and yet tantalisingly out of reach.

Thirteen letters were sent from Elizabeth to China in the second half of the 16th century in a desperate push for access. Some travelled south and east, around the Cape and into the Indian Ocean, others northeast or west into icy Arctic wastes. Not one reached its destination, the English ships that carried them were lost to inclement weather, mutiny or piracy. A diplomatic mission to China would remain a fantasy until the late 18th century, when George Macartney famously refused to kowtow before the Chinese emperor in 1793. If Global Britain’s post-Brexit advances to Beijing take that long to bear fruit, we need to think in terms not of a two-year “implementation phase,” but a 200-year one.

And even once that 1793 breakthrough came, Emperor Qianlong failed to see what the British could offer. He wrote imperiously to George III: “As your ambassador can see for himself, we possess all things. I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures.” Oh dear.

Unlike Macartney, 21st-century British diplomats are prepared to prostrate themselves before China in the drive to secure a close post-Brexit alliance, but it is not obvious that we’re getting much in return. May’s trip produced fewer bankable wins than she’d have hoped: as Fraser Howie commented, “they have all the cards… Britain has absolutely zero leverage.” To Elizabethans it would be a familiar story.

V: You can’t keep clear of the Continent for long

After decades of struggle to assert England’s place in the world, Elizabeth I died in March 1603. Her successor James I came to the throne with a very different set of priorities: by instinct a unifier, he immediately sought to broker peace with the rest of Europe. He therefore steered the crown decisively away from the alliances cultivated by his predecessor, to the lasting chagrin of English merchants and diplomats. Disgusted by Elizabeth’s trade-driven realpolitik, he refused even to sign letters to non-Christian monarchs and felt that dabbling in commerce would demean his divine office. Hardly your archetypal remainer, he nonetheless brought Britain back into the mainstream of Europe. Elizabeth’s attempt to carve out a new role for England in the world beyond Europe died with her. Theresa May should take note.