Less than a month after unveiling the latest version of its AI video tool Sora, OpenAI has been forced to put new guardrails on the app—where users share a TikTok-like feed of videos generated from user videos and text entered as a prompt.

The Sora network is currently open only to a select set of “beta” user-testers, and is filled with videos of these users—mostly young men—in racing cars, rollercoasters and rockets, sometimes interacting with famous historical figures.

And who could have imagined that, in a country rapidly dismantling civil rights laws, users might make AI videos of civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr saying vulgar and racist things? After Reverend King’s family protested, OpenAI now restricts the ability to make MLK Jr videos, and is open to requests from the estates of other public figures to limit posthumous use of their likeness.

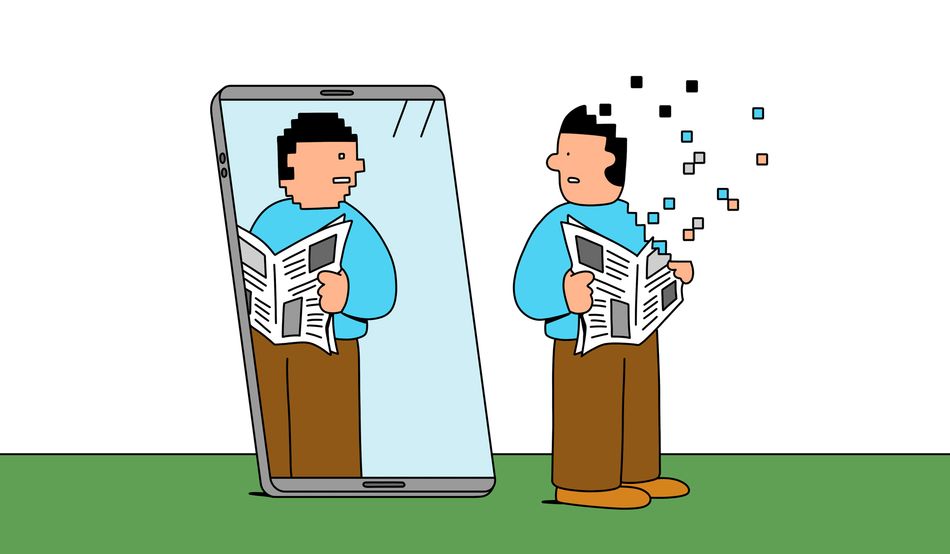

AI video has risen so fast it seems reasonable to fear that convincing deepfakes will undermine journalism as we know it. At a moment of epistemic challenge, where an AI tool can quickly render video that never happened, we might expect political leaders to urge caution about these tools and remind us that what we see cannot always be believed.

Not in the age of Trump.

After “No Kings” demonstrations brought an estimated five to seven million Americans onto the streets in October, the US leader shared an AI-generated video on his social network, Truth Social, where a crown-wearing Trump flies a jet named “King Trump” over protesters, on whom he drops excrement.

The video is not meant to fool viewers: not even Trump’s most enthusiastic fans would believe he could fit into the cockpit of a fighter plane. But it is part of a wider story. The New York Times reports that Trump posted 19 fake images and videos during his 2024 presidential campaign, from the outright absurd to the more plausible—such as a woman wearing a “Swifties for Trump” T-shirt. Since his election he’s posted 28 AI images and videos, including self-portraits as a king and as the pope. For anyone worried that AI-generated imagery might become a routine part of political influence operations, that horse has left the stable.

As Trump becomes the AI slop president, fake imagery is seemingly undermining our sense of shared reality, and not always in ways we might expect. Sceptical that footage of the No Kings protests in Boston was authentic, a user uploaded screenshots of a news video to GrokAI, the large language model Elon Musk has repeatedly “tuned” to make it less “woke”. Whether due to its programmed biases or simply because detecting the origins of video is difficult, Grok misidentified the imagery as recycled footage from a 2017 rally. Right-wing influencers seized on the idea that anti-Trump forces had lied about their crowds—a false claim amplified by, among others, Senator Ted Cruz.

When an AI misidentifies real footage as false, we’re entering a weird moment for truth. BBC Verify has fact-checked professional and citizen journalism for the past two years, using open-source intelligence and satellite imagery to determine authenticity. In June, the service declared a new focus on AI-generated content and its fact checks have since been roughly split between debunking fake content and assuring us that reality is real.

Work like BBC Verify requires significant investment, and it’s here that AI might present the greatest threat to our common understanding of the world. While public service media anchors a sense of shared reality in many nations, commercial media captures a much greater share of viewers and readers in almost all markets, including for news content. And AI is about to kick a key support out from under the commercial news business model.

Commercial media has been heavily dependent on advertising ever since newspapers were invented. The internet has slowly eroded that revenue model, with advertisers moving to social media and video platforms instead of newspaper and television. Here, amid a vastly increased supply of media, digital ads command a tiny fraction of the price of print ads, leading to a fierce war for attention that’s bent news media in predictable ways. It’s easier to generate clicks with reporting that inspires strong emotion and so media has often become more partisan, more sensationalist and less nuanced.

AI promises to accelerate revenue decline in at least two ways. First, AI chatbots can generate great volumes of text with minimal effort, allowing unscrupulous authors to create “content farms”. These are closely interconnected webpages that offer little original information but which look like high-quality content to search engines—which see hyperlinks between pages as signals that a page is useful and authoritative. Web search has become increasingly frustrating as interesting, original content is buried under a thick layer of AI slop.

Dissatisfied users are turning to AI chatbots to answer questions instead of searching the web. The latest generation of chatbots are capable of querying news sites for answers to questions about breaking news. Often—and increasingly—these chatbots are confidently wrong, repeating false or debunked claims. A recent study from fact-checking site NewsGuard found chatbots responding to queries about the news with falsehoods 35 per cent of the time—roughly double the rate of a year prior.

Newsguard explains that the rise comes from AIs being programmed to answer questions even if they are uncertain if an answer is correct. A year ago, AI bots would refuse to answer questions about the news 31 per cent of the time, while during this more recent round of tests the bots never refused to answer.

Not only are these over-confident bots spreading misinformation, they are making it harder for users to find authoritative sources. Online news sites report traffic has decreased sharply as Google serves AI-generated summaries in response to many search queries.

A Pew Research Center analysis of web browser logs from 900 users suggests why: users who received an AI summary were only half as likely to click on a link in a search as those who only received a list of links. Users almost never clicked on links provided in the AI summaries themselves—these represented 1 per cent of clicks in the sample. Many users relied on the AI summary—accurate or otherwise—and did not bother to verify the AI’s answer or enquire further.

Companies like Google are investing billions in AI, and are unlikely to slow its integration into their tools for fear of damaging the news industry. Instead, Google is releasing a version of the Chrome web browser with an AI assistant baked into it. But the problem seems obvious to anyone who is not a tech executive: AI needs news to answer questions about the world, but is undercutting the business model of news-gathering organisations.

A few may survive through subscriptions and licensing deals, but the current economics don’t look good. The New York Times—which is suing OpenAI and Microsoft over alleged unauthorised use of its news content—made a licensing agreement with Amazon worth $20m-$25m a year, a small fraction of its advertising revenue ($506m annually). And while major players like the Times can afford to negotiate these licensing deals, most local journalism outlets cannot.

With the embrace of AI video generation for political gain, it is likely that soon a major election will be influenced by imaginary imagery. Governments’ impulse may be to rein in video generation software like Sora, likely through mandatory watermarking of AI content. But such controls can easily be bypassed in open-source versions of the big AI models.

It could be far more important to ensure we have robust public service journalism. Reporting and fact-checking—our best tools for anchoring debate in a shared reality—must continue to be financially viable and available.