Much has changed since the dark days of the pandemic in 2020, when the BBC Proms was reduced to broadcasting repeats from the archives, with a rump of live concerts performed behind closed doors during the season’s final two weeks. The current season, playing out at the Royal Albert Hall until 14th September, is the last to have been programmed by outgoing director David Pickard; his successor, also the new controller of Radio 3, Sam Jackson, is no doubt already working on 2025 and beyond. There’s a palpable sense that, since Covid, the BBC has not only tried to build back better but also cannily reinvent the whole idea of the concerts—especially with the prominence handed to music from outside Western classical tradition; jazz, rock and pop, in particular.

One person’s expansion of repertoire is another’s betrayal, and few things about the current Proms provoke more sneers than these swerves away from classical music. Belying the peppy, Blue Peter-presenter chirpiness with which the Proms is presented these days, the BBC’s collective nervous breakdown over classical music in 2023—when it threatened to throw the BBC Singers under a bus, while obliging the BBC’s classical divisions to think more commercially—still leaves devotees’ nerves jangling. Trust between the BBC and its classical music audience was tested as never before, with many members of the latter group reaching the conclusion that the corporation’s high-ups have little understanding of classical music—and may even wish it harm. The BBC remains the custodian of a music festival, the Proms, with a history stretching back to 1895, a festival entirely synonymous with classical music in this country. So why concerts featuring Sam Smith? Disco? Northern Soul?

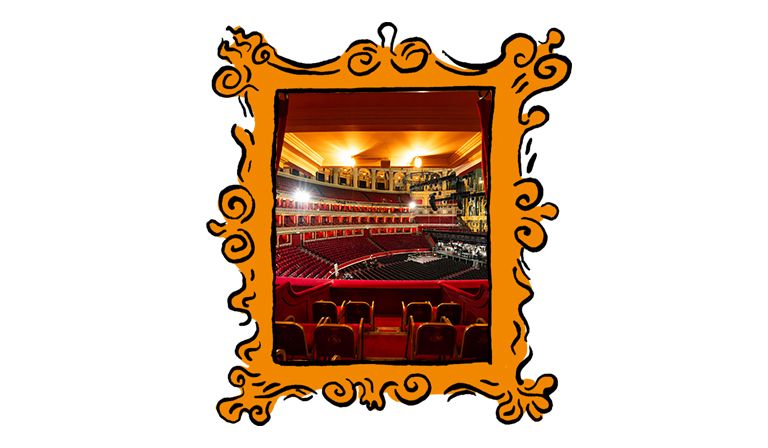

I come here not to explain Sam Smith at the Proms, rather to throw in some perhaps inconvenient questions, as well as, I hope, some helpful observations. Last week, as I sat in the Royal Albert Hall, listening to a troupe of free-jazz improvisers playing music by the Chicago-born composer Anthony Braxton, working alongside the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and conductor Ilan Volkov, I was in a forgiving mood. No symphony orchestra in London—not the LSO, nor the Philharmonia or London Philharmonic, not even the BBC Symphony Orchestra, which would once have relished rising to the challenge—would dare uncork Braxton’s radicalism these days. The Proms provides a utopia, free from the usual pressures of box office, where music like this can be given a platform. And what a liberating noise it was; music to rearrange the very molecules of your soul.

Braxton, 80 next year, and active since the mid-1960s as jazz saxophonist, free improviser, composer and theorist, is a colossus of modern music, prolific and massively influential, and a truly generous spirit. He was due to perform in his own piece, but unable to travel because of health concerns. So his place was filled very ably by the German-born, New York-based saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock, who performed alongside a group of Braxton acolytes. Despite the main man’s unavoidable absence, I felt cheered that, at last, the BBC had grasped a fundamental truth about how such music operates.

The problem is not that the Proms engages with music outside the classical tradition, it’s that too often such programmes have not been given the thought they deserve. Jazz tends to be dished up as “tribute to” evenings—recently to Charles Mingus, Sarah Vaughan, Aretha Franklin and Nina Simone—with the very edge that made the original performers so alluring suffocated under unwieldy orchestrations. With rock music, the same problem. A well-meaning tribute to David Bowie, a few months after his death in 2016, was widely ridiculed for fussy post-minimalist orchestrations that soft-pedalled the spirit of dark voodoo that haunts albums such as Outside and Blackstar. This year, a concert focused on Nick Drake suffered similarly—it sounded all the notes but missed the music by a mile.

But Proms HQ mustn’t duck the challenges, rather tackle them head on. Three paragraphs on, I’m still at a loss to explain Sam Smith—a crazily popular artist who could easily fill the Albert Hall many times over and pay for an orchestra of their own; why the BBC’s precious music budget must fund such an unapologetically commercial operation is beyond me. My message to Sam Jackson: be courageous, listen hard, hone your antennae to find those musicians from outside classical tradition whose work can stand as its equal. Imagine Brian Eno or Autechre flooding that cavernous space with glorious electronic sound; have Laurie Anderson or Meredith Monk bring one of their fantastical evening-long pieces; commission new work from composers such as William Parker, Roscoe Mitchell and Tyshawn Sorey, who open up spaces between composition and improvisation—and can be present to make a case for their work. Partner with other institutions too—was the idea of a Yoko Ono Prom, pegged to the current exhibition at Tate Modern, so obvious that nobody thought of it?

None of this music needs to be validated by being turned “classical” against its will. The Braxton concert recognised that jazz, like rock or pop, doesn’t work well as repertory music. And that’s the way to go in future. This is a performer’s art, music about now—not about paying tribute to past glories.

How the Proms has changed...

...and how it should change some more

August 22, 2024

© PJPHOTO / Alamy