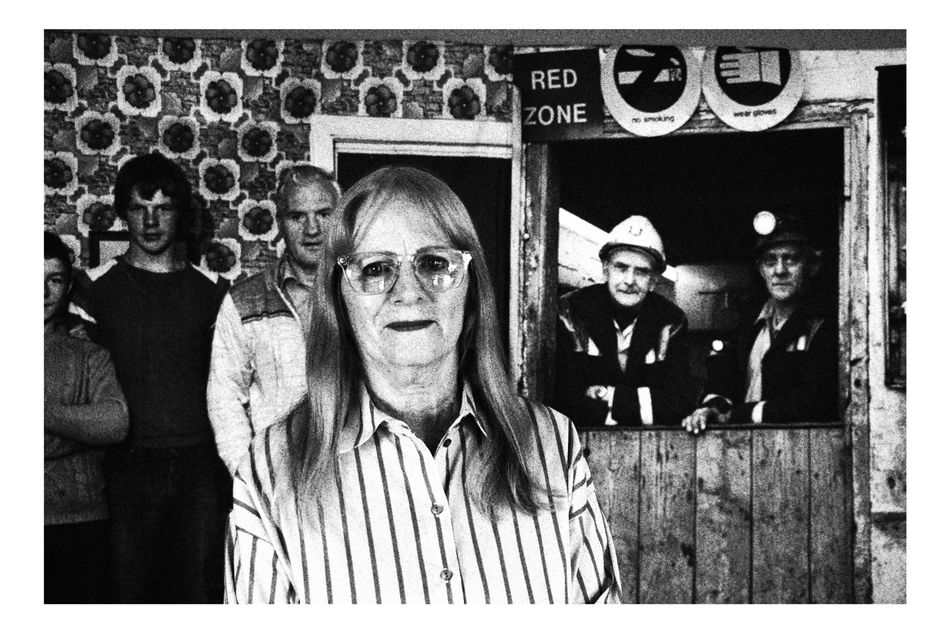

Betty Hunter comes from a long mining lineage in Cardenden, west Fife. In this photograph, taken in 2023 by artist Nicky Bird alongside colleagues at the National Galleries of Scotland, she stares into the camera with a determined look. At first glance, Hunter seems to be in crowded room. But the illusion is only temporary: she is in fact alone here, the men behind her themselves only photographs captured many decades earlier.

In the photograph to the right of Hunter stand two workers who have ascended to the surface via lift. They look content to have reached daylight, with coaldust visible on their hands. In the photograph to the left is a living room scene of a middle-aged man posing with his two sons. Hunter stands contemplating—around half a lifetime later—what this lost world means for generations of men and women who grew up in localities such as Cardenden, where coal remained king from the Victorian era right up to the late 20th century.

Both the images behind Hunter were taken by the American photographer Milton Rogovin in 1982, when he was welcomed as a guest of the National Union of Mineworkers. They are from the Scottish section of Rogovin’s “Family of Miners” project, which compiled hundreds of photographs of miners from as far afield as China and Zimbabwe. In Scotland, Rogovin was particularly drawn to the coal communities of the Central Belt and their reputation for trade union radicalism. Not long after his visit, Rogovin’s photographs came to represent a crucial turning point in British industrial history. Around a decade later, Scottish colliery employment had virtually disappeared, confined only to the drift mines of the Longannet complex before it too closed in 2002.

Bird came across Rogovin’s work a decade ago. She decided to revisit some of the same—though much changed—places as he did in Scotland, among them the former coal communities of Ayrshire, Midlothain and Fife, to reinterpret the meaning conveyed by his photographs long after Scotland’s era of underground work had ended. The results are now on display as part of this new exhibition at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

In the picture of the miners in the lift, subtle hints point to the industry’s inherent dangers, but also the measures introduced to help make it safer after it came into public ownership in 1947—a warning sign, for instance, telling workers not to smoke. Contraband rules were enforced by both National Coal Board officials and the miners themselves, the latter of whom applied a particularly rough and ready justice, knowing as they did first-hand the price of taking risks. Although not without its dangers, mining at this time offered relative economic security, and wage improvements won by strike action during industrial disputes in the early 1970s reinforced a sense of optimism in the coalfields.

Women were legislatively banned from underground work in 1842. Nevertheless, Hunter spoke to Bird—in a reflection recorded for the exhibition—with familiarity about the miners in the pictures, despite not knowing who they were. She insists these men carried “the look” her grandfather, uncle and father had shared in their “hard work and struggle”.

Hunter also told Bird about the difficulties the children of miners faced throughout the era of coal mining and in the aftermath of the miners’ strike, in an industry where men had to “follow the work”. It was typical of families to move and have to integrate into new localities, as well as face the consequences of industrial disputes, some of which included criminal convictions.

It was not long before Bird met Hunter—but after a long-fought campaign by union activists and mining families—that the Scottish parliament issued a pardon to those convicted of breaching the peace and other offences during the strike of 1984 and 1985.

The world of Rogovin’s photographs might be gone. But, to this very day, its consequences are still being felt.

Before and After Coal: Images and Voices from Scotland’s Mining Communities is on display at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery until 15th September