The past is always present. This is true for all of us, but it seems to be pressingly, possessingly true for the political philosopher Lea Ypi.

She wrote about both her own and Albania’s past in Free, the 2021 book that turned this professor at the London School of Economics (LSE) into a literary star in the UK but was altogether more contentious in her home country. “There was a lot of controversy around Free,” she explains over breakfast in a restaurant near the LSE campus, “which had to do with how I was depicting the communist period.” Albania, let us not forget, went through fascism, communism and an attempt at liberalism in the 20th century, before enduring what Ypi describes as “a kind of civil war” in the 1990s. Its past is always present, too.

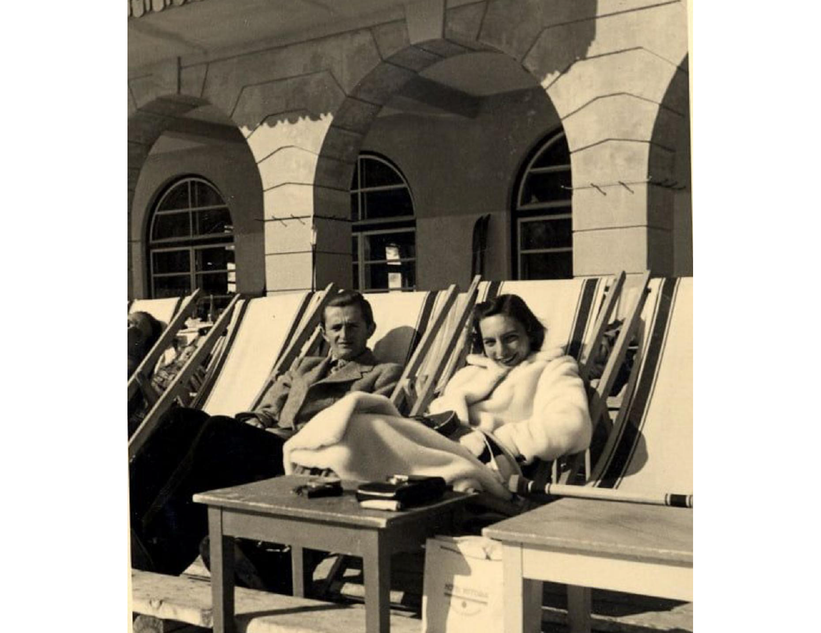

Which goes some way to explaining the response to a photograph of Ypi’s paternal grandmother Leman that was posted on Facebook after the publication of Free. To the innocent observer, there may be nothing of note about the image: it shows Leman smiling from a sun lounger beside her husband (and Ypi’s grandfather) Asllan—they were on honeymoon, in the Italian Alps, in 1941. But to Albanians with axes to grind, it was an incitement. These people don’t just know Ypi; thanks to her family’s role in the country’s politics across decades, they also know Leman and Asllan and the fact that he, a son of a former prime minister, was imprisoned by the communist regime for many years. Some seized the opportunity to berate Ypi for this—as though, because she is on the left, she sympathised with her grandfather’s captors; as though it would prove anything other than their own misogyny. “You dishonoured not just your grandmother but all the victims of communism, you communist bitch,” read one of the many comments underneath the post.

This photograph—and the awful reaction to it—is the motivating incident of Ypi’s new book, Indignity. She had never seen it before. It had been posted online by someone with the username of Çim who regularly publishes photos from Albania’s turbulent past, although, in this case, Ypi suspects that he was looking to create some turbulence of his own: “It was clearly intended as a provocation because it was presented as my grandmother,” she says. But it wasn’t the resultant insults flung in her direction that bothered her; it was those directed at Leman. “The grandmother too was a bitch,” read a subsequent comment. “Perhaps not a bitch, but a communist spy. And before that, a fascist collaborator,” added another.

When Ypi talks about her grandmother, who died in 2006, her features waver between joy and sadness. “She was the person who brought me up, almost single-handedly,” she says. “There were two phases and she was really central to both of them.” The first of these phases—perhaps evidence of how the personal and political coalesce in authoritarian states—was under communism: “In communist Albania, parents worked all the time and you didn’t have after-school clubs or babysitters… so my grandmother became the person I turned to every time I needed something.” The second phase was post-communism: “The 1990s were really hard. Coming of age in that period was really hard. And, again, she became my main anchor—she was the only person who could just read my diaries.

“That was why we were so close, because she went from being a kind of parental figure to a friend figure.”

So, seeing her grandmother traduced on the internet stirred a lot of feelings in Ypi. Partially, she wondered how Leman could have appeared so happy even on her honeymoon, when that honeymoon was taking place in an Axis nation during the Second World War—and whether the happiness was real. Partially, she speculated as to the truth of the online trolls’ accusations. But mostly, her reaction was a defiant sort of philosophical inquiry: “It really raised the question, for me, of what happens when someone can’t make a case for themselves,” she explains, jabbing at the table. “Who has responsibility and authority to reflect on their legacy and interpret it? Just because you’re a family member, are you the one who can speak for them? Or is there a public that has the same right to interpret this legacy?

“It’s all really connected to this question of dignity that keeps coming up in the book. This is the first real example of it in its pages: does someone’s dignity require them to be alive?”

Ah, yes, dignity. It does indeed keep coming up in the book. The word itself or words like it—dignified, dignitaries, and so on—appear 75 times. (Although the title word, “indignity”, appears only once, by design, in the very last sentence.) As it happens, the last of the questions Ypi asks above—about whether someone’s dignity requires them to be alive—is dispatched swiftly: “Dignity is something we have just because we’re human,” she says, “so, in that sense, it doesn’t matter if you’re dead or alive.” But a hundred other questions do follow on from it. Indignity is, in a way, an exploration of different ideas about dignity, from those of the Stoics to those of Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche and beyond—but we shall get on to that later.

First, an explication of Indignity’s style and structure. After encountering this photograph of Leman online, Ypi decided to go in search of both it and her grandmother’s past. She contacted Çim—the person who posted it and who remains a mysterious, evasive presence throughout the book—and winds up in the secret service archive in Tirana, Albania’s capital, where she accesses the files kept on her family by the old communist state. Ypi tells of this archival digging, in Albania and subsequently Greece, in several punctuating, first-person chapters that are often mordantly funny. In between those chapters come the results of that research—her grandmother’s story, from youth to old age—but in novelistic form. Here is a multi-charactered narrative that spans the decline of the Ottoman empire to the rise of fascism in Europe to the Soviet era. The characters have conversations that Ypi can’t possibly have heard. They have inner lives she can’t possibly have known. They are both made up and not. Which is to say, Indignity is a blend of nonfiction and fiction.

This is no bad thing, not least because there is something of Lampedusa’s The Leopard in both the setting and virtuosity of Indignity’s narrative parts. But it does raise questions about honesty: if Ypi is, on some level, trying to tell the truth about her grandmother, how much poetic licence can she take with the history? “This goes to the heart of the book,” says Ypi. “The question of method is not separate from the substance of the book and how we reconstruct dignity”—but we shall get on to that later, too.

For the time being, she explains, “It started out as basically a memoir, a kind of family history, but the more I grappled with the gaps in the archives, the more it was clear that you can’t do everything through history.” So, instead, she created rich characters and situations from a position of knowledge, whether that knowledge came from Ypi’s memories of her conversations with her grandmother or from yellowed newspaper clippings in university archives. “You can’t write about individual history,” she continues, “but you can create an individual character that relies on historical facts that you can find around other characters.”

What does that mean? Ypi details the process for one of the book’s most memorable characters, Leman’s aunt Selma, a fiercely freethinking member of the family when its home was Salonica (or Thessaloniki), in Greece, in the earlier decades of the 20th century. “I say, for example, about Selma, that she was wearing this. She was going here. She bought the dress in this shop. All of these places really existed in Salonica at the time. The best example, because I spent so much time researching it, is when I say that she and my grandmother went to eat at the Patisserie Doré, where Atatürk used to drink from these red cups. The patisserie really was there. Atatürk really drank from those cups. And they really were red. You can read about the role Patisserie Doré played in the 1930s in Salonica, but this is very hard because it’s all micro-histories and it’s all in Greek. You have to learn Greek to do it. I don’t speak Greek very well, but I can now read it—to go through files and material.”

Besides, Ypi is trying to get at bigger truths than just the plain truth. As well as being a person, Selma is also a sort of symbol. She tells the young Leman a parable about being in “a room full of smoke”, where “you find yourself gasping for air”. “Would you leave,” she asks, “or wait for help?” We don’t have to guess at Selma’s own answer: she killed herself on her wedding day rather than succumb to an unhappy marriage, arranged by her brother, with the upright, uptight German tobacco magnate Gustav. Her death, the whole smoky room analogy, stands in for a Stoic version of dignity, explains Ypi—and returns throughout the rest of the book to be challenged, tested and understood. As Leman herself wonders, “Would it have changed anything if I had known back then? If I had told [Selma] as a child what I discovered as a grown-up? … What if there are other people in that room? What happens to them?”

Even Gustav, Selma’s dreadful would-have-been husband, is a symbol; perhaps even more so, since, as Ypi admits, his return later in the book—as a Nazi party member warning Leman and her family to flee ahead of the “new eagles” who will pick off the “lambs” of Albania after the war—is not strictly historically true but does serve a philosophical purpose. “His dialogue with Leman about lambs and eagles,” Ypi says, “is straight out of Nietzsche. There’s a Nietzschean view of dignity and there’s a Kantian one, and these are two polar opposites. This is the clash of those two worldviews. The character becomes a vehicle for philosophical discussions.”

Ypi’s sympathies—in fact, a large part of her academic interests—lie with Immanuel Kant and his view of dignity. Or perhaps it is slightly more accurate to say that they lay with Kant. “Basically, from the Kantian—or from my—point of view, dignity consists in the free will and its capacity to assert itself against circumstances, even very adverse circumstances,” she summarises. “But throughout the history of philosophy there are lots of different ideas of dignity, and I didn’t want the book to just hammer home one. I wanted to problematise it.”

And problematise it she does—or, rather, the world does. One thing that Indignity explores is what happens when philosophies meet history, when decisions have to be made at the point of a gun. Should Leman have fled the incoming communist regime in Albania, with what it would mean for her and her husband? In the moment, this was not actually a debate between Nietzsche and Kant and their respective views of dignity. And you don’t have to be a Nietzschean—and certainly not a Nazi—to believe that Gustav may have had a point.

This helps to explain why the literary qualities of Indignity are so important for Ypi. “Humans are complex, and you want to give them the benefit of the doubt at all points of their lives,” she starts. “And I think literature is so powerful because it can do that; as opposed to when I write philosophy, when you have an argument, you want to show what’s right and wrong and then you defeat all the objections… In philosophy, you’re always dealing with universals. Whereas you can’t do that in literature, or you’d be writing bad characters and bad stories.”

Ypi isn’t just pursuing the story of her own grandmother, she’s also working out intellectual problems for her own interest

If all this talk of philosophy and its limitations makes Indignity sound drily didactic, rest assured: it is not. Take it, instead, as an indication of how stunningly multilayered the book is. On the surface, there is the drama and emotion of Leman’s story. Underneath, there is literal subtext concerning philosophy, literature, history and more. It is to Ypi’s credit that none of this is really signposted; the reader is free to dig as deep as they like, or not. It adds to the sense that this is an entirely personal work: not only is Ypi pursuing the story of her own grandmother, she’s also working out intellectual problems for her own interest and edification.

But where does all this take her—and us? It is not too much of a spoiler to say that Ypi didn’t find the original photograph of her honeymooning grandparents before finishing the book, nor that Leman’s files in the Albanian secret service archives may not be entirely accurate… or even wholly about this Leman. Still, despite these impediments, Indignity does reach some big conclusions.

“The question is,” says Ypi of her book’s end, “how do you capture reality when you don’t trust the mechanisms through which the truth can be captured? Because, at that point, even language is indignity. The final message of the book is that you can only do this by moving between philosophy and fiction. That’s why the final sentence of the book includes indignity—indignity defied through imagination. The only thing you can do is reconstruct these situations with the help of all the different tools we have—like history, literature and philosophy—and hope that telling the story will somehow give us an approximation of this idea that everyone has been chasing in ways that we don’t quite know.”

In the final pages of Indignity, Ypi reveals the regret she still holds for the eulogy she gave, as a student who had to hurry home from Italy, at her grandmother’s funeral. “It didn’t sound like me,” she writes. “It sounded like something I had just read, something I had been asked to repeat.” She goes on to confess: “I am still trying to correct my mistake, to find the right words, to mark her passing in the right way.”

Now, almost 20 years later and with the publication of her latest book, has Ypi finally found the right words? “I don’t know if I found her words, but I think I found words that she would probably agree with.” She pauses, before continuing very carefully: “This is a much richer, more complex understanding of her life. In a eulogy, you’re just basing that on what you know and what you’ve experienced; it’s immediate and completely emotionally dependent. Whereas, with this book, there is a bit more—and that is why I think my grandmother would have been happy with it. She wasn’t someone who would just go in for the emotional.”

And, with that, Lea Ypi picks up her bag, says a friendly goodbye and heads back out into the ever-present past.