How to distil so colourful and complex a life as that of a man who arrived in London just before the Second World War as a penniless Austrian-Jewish refugee, but went on to become Baron Weidenfeld of Chelsea and one of the leading lights of 20th-century publishing, whose reach and power impacted the culture of ideas across Europe, Britain and America? Journalist and writer Thomas Harding’s biography of George Weidenfeld—co-founder and publisher of Harding’s book’s own imprint—makes the inspired choice of leading with the books that built the publisher’s fame and fortune. Though, in truth, it’s Weidenfeld’s skill at networking (not to mention his penchant for marrying heiresses) that more often brought in the latter.

The Maverick is organised around 20 key texts, both fiction and nonfiction; some controversial, some classics and others that never made it into print. (Mick Jagger’s failed autobiography cost Weidenfeld £42,500 in 1985—over £120,000 in today’s money.) It’s a fittingly eccentric approach, but also a canny structural move, not least because—as the book’s subtitle suggests—this is both Weidenfeld’s story and that of the postwar glory days of publishing.

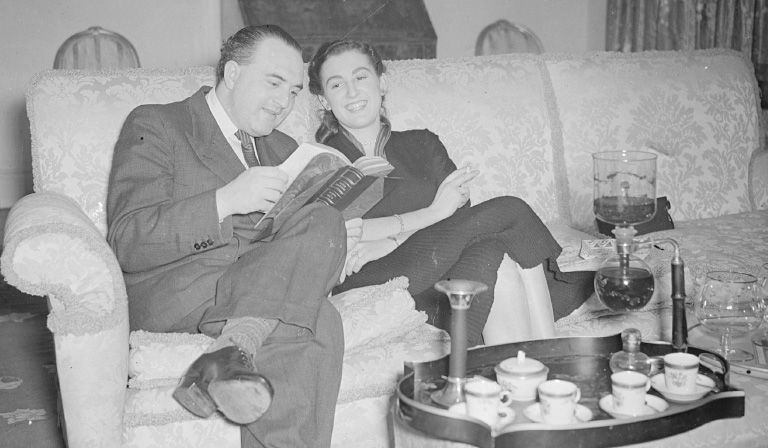

This was the era in which publishers began stepping out from behind the buffer of their imposing Victorian desks—where they sat, as Harding describes it, “in their tweed jackets, drinking coffee, thumbing through manuscripts or reviewing their warehouse stock”—to become movers and shakers in the wider cultural landscape. And nobody embraced and embodied this “new type of publishing executive” as wholeheartedly as Weidenfeld. “He saw books as a way to impact the political discourse,” Harding explains: “his natural habitat was the cafés and restaurants where the artists and intellectuals hung out, the salons and parties where the edgiest writers of the day could be found.”

And if the people Weidenfeld met weren’t writers already, he often tried to make them so. The fellow Vienna-born British writer and commentator David Pryce-Jones tells Harding about a memorial service he once attended with the publisher: “Afterwards, when we came out he said, ‘Look at all these people, do you see, there’s a book in that?’ How many people leave a memorial service thinking about how to make a book out of the congregation? It was the way George was. He had an incredibly fertile mind. He was full of ideas.” Or, as the long-time editor of British Vogue Beatrix Miller puts it in a quote used as an epigram at the beginning of Harding’s book, “George sees everyone he meets as a potential book.”

How many people leave a memorial service thinking about how to make a book out of the congregation?

Arthur George Weidenfeld was born into a modest Jewish family in Vienna in 1919. Amid growing persecution by the Nazis, he fled to England in 1938, where, during the Second World War, he found work using his aptitude for languages with the BBC; first with their monitoring department, and then later as a radio correspondent and commentator, helping to produce more than 20 current affairs shows a week. His other great skill was his personableness; what Harding describes as his “bottomless appetite for social engagement”—though, interestingly, he was a teetotaller himself, sipping on Earl Grey tea, milk or apple juice while everyone around him was quaffing martinis or champagne.

Shortly after the end of the war, Weidenfeld founded the monthly literary magazine Contact, which he envisaged as a British equivalent of the New Yorker (a successful version of which is yet to materialise on this side of the pond). Though the magazine itself was relatively short-lived, its legacy was the publishing house Weidenfeld & Nicolson. The project’s transformation from one to the other was not an act of shrewd foresight, but happenstance. Because of rationing, paper wasn’t readily available for new periodicals, but book publishers were allowed unlimited quantities. If he distributed the magazine “under the umbrella of a book publisher,” Weidenfeld could gain access to all the paper he wanted. All he had to do was release a few books a year.

Thus, in early 1947, with the backing of a deep-pocketed business partner, Nigel Nicolson—son of the writer Vita Sackville-West (famously, the lover of Virginia Woolf) and her diplomat-turned-historian husband Harold Nicolson—George Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd came into being. They published their first five titles in November 1949.

The venture was further helped by a large investment from the coffers of the wealthy family of Weidenfeld’s first wife, Jane Sieff. (His “casual infidelities” ended the union only three years after he and Sieff were wed, but not before the birth of a daughter.) Next came Barbara Skelton, Weidenfeld’s entanglement with whom began as an affair while Skelton was still married to one of Weidenfeld’s own authors, Cyril Connolly. (In just one of the sexual and romantic games of musical chairs that are touched on in the book, Connolly was himself having an affair with the writer Caroline Blackwood, who was then married to the painter Lucian Freud.) Trying to explain the situation to his concerned parents, Weidenfeld played up the drama, describing Skelton as “his Mrs Simpson”. Though in her own delightful (and sadly out-of-print) memoir, Weep No More (1989), Skelton tells a different story, describing living with Weidenfeld even before they were married as a “lonely and barren” experience. Unsurprisingly, the marriage didn’t last.

Weidenfeld, however, was just getting started. His third wife was the American heiress Sandra Helen Payson—they married in 1966 and divorced 10 years later. His fourth and final spouse was Annabelle Whitestone, whom he married when he was 73 and she was 48, and with whom he remained until his death, in 2016, aged 96.

Weidenfeld & Nicolson’s raison d’être was, in Harding’s words, “to publish authors whose voices were normally shunned by mainstream publishers: the mavericks, the scandalous, the subversive”—Weidenfeld’s own focus was on European refugees and women writers. It’s an avowal that sounds uncannily familiar to the supposedly forward-thinking mission statements that a host of publishers have made in recent years. On the other hand, though, Weidenfeld’s roving intellectual and business eye was, as the German media mogul Mathias Döpfner put it, “the opposite of cancel culture”. If anything, Weidenfeld courted controversy.

When it came to nonfiction titles, for example, although a passionate supporter of Israel all his life, Weidenfeld published books by a large number of high-profile Nazis. These included Hitler himself and many men who served under him, most notably Joachim von Ribbentrop (Hitler’s foreign minister), Rudolf Höss (the commandant of Auschwitz) and Albert Speer (the regime’s architect). And Harding cleverly but subtly draws attention to the oddness of this by positioning the chapter that deals with these titles immediately after that about Max Hastings’s biography Yoni – Hero of Entebbe: Life of Yonatan Netanyahu (1979), which appeared in a bowdlerised version after Weidenfeld bowed to pressure from the Netanyahu family (Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s current prime minister, is Yonatan’s younger brother) to present the subject of the book in an entirely positive light. Hastings himself, then a relatively young journalist with significantly less power than his esteemed editor, described the experience as “humiliating”. As recently as 2021, Harding reports, when asked for his opinion on Weidenfeld, Hastings declared the man to have been “in every way a loathsome human being”.

Although a passionate supporter of Israel, Weidenfeld published books by a large number of high-profile Nazis

Weidenfeld was equally daring when it came to the fiction titles on his list, publishing Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita—a novel that is still garlanded in notoriety—back in 1959, and taking on the British obscenity laws in the process. And while the publication by Penguin, the following year, of the unexpurgated version of DH Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover is perhaps better known as a landmark case, it was the argument successfully used in favour of Lolita’s release—that of the novel’s literary merit—that paved the way for the eventual triumph with Lawrence’s novel.

By focusing on the bigger names and titles with whom Weidenfeld worked, Harding ensures that this book has the widest appeal. Unlike, say, the book by Weidenfeld’s one-time flatmate Diana Athill, Stet: An Editor’s Life—her charming but rather niche memoir about her career at André Deutsch (another eponymous imprint founded during this era by a forward-thinking, literary-minded European; Deutsch was Hungarian)—Weidenfeld’s story involves surprisingly little time editing manuscripts. Rumours apparently abounded that he never read the books he published. Harding often refers to his subject’s “impatience”—something that didn’t help the writing of the memoir he published in 1994, Remembering My Good Friends, a book that was embarrassingly rife with errors and little more than an elaborate exercise in name-dropping—and he also quotes a letter from the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, written to the art historian Bernard Berenson, in which the former declares that Weidenfeld has “no literary judgement… He is, alas, quite illiterate, and doesn’t know how to begin to distinguish good from bad.”

Yet rather than set out to solve these conundrums and contradictions, Harding seems content to accept they are part and parcel of his idiosyncratic subject. The result isn’t unsatisfactory, but it leaves one with questions. Weidenfeld ultimately remains a somewhat impenetrable figure; a feeling that’s encouraged, perhaps, by the book’s unusual structure. For instance, we’re two-thirds of the way through and in a chapter set in the late 1970s it’s mentioned that, 30 years earlier, when he was 28, Weidenfeld took a year-long hiatus from the London literary scene to work as chief of staff to Chaim Weizmann, Israel’s first president.

For the most part, though, Harding’s approach works exceptionally well and allows him to cover a huge amount of ground. Although undoubtably a volume of interest to anyone involved in the world described therein, it’s written with a lay reader in mind—and will inform and entertain in equal measure.