By the Wye is a glamping site that could tempt almost anybody to spend a night under canvas. Its five spacious safari tents are pitched on handmade platforms in a steep patch of mixed woodland that stretches down to the river, just a few yards from the Welsh-English border. Visitors can watch a family of goosander ducks diving for fry, an egret and a heron competing for the best fishing spot, an occasional otter eating her catch. Or they can take an easy walk over the bridge into the market town and tourist magnet that is Hay-on-Wye.

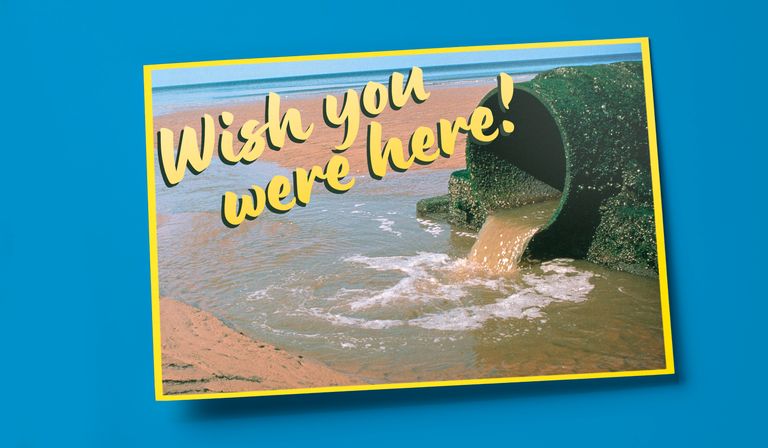

Its owners do, however, have one problem. “That overflow pipe,” said Dawn Farnworth, who established By the Wye with her husband, Steve, five years ago. “It never just trickles out, it gushes out. It’s like they turn on a tap, and suddenly it’s go.”

Hay’s main sewage pumping station sits directly opposite their campsite, on the far bank of the river. It’s a shabby structure of brick and stained concrete, with a galvanised outdoor staircase running up to a door on the first floor, which looks like it hasn’t been maintained for a decade or more. The fascia boards are rotten, one of the windows has a hole in it, and the guttering downpipe has come loose and blows around in the wind. Weeds grow through the cracks in the concrete drive, across the gravel forecourt, and have started colonising the building itself. Two overflow pipes, one with a blue cap, the other with a green, which do at least look freshly painted, run into the Wye from the bank below.

“Whenever there’s rain, or even when the river is just up a bit, water comes gushing out. I get blown away by the amount of toilet paper and all the other stuff coming out, things that people put down the loo,” said Farnworth. The pipes are “only supposed to vent in extreme circumstances, but this is so much more than that.”

The pumping station opposite the Farnworths’ campsite vented sewage straight into the river on 74 different days last year, for more than 188 hours. It’s a sign of how low standards are for the water industry that this is not in fact too bad in comparison with elsewhere on the Wye. In the village of Moccas just over the border in England, the sewage works vented for more than 2,000 hours last year, while the works in Redbrook in the Forest of Dean vented on 140 different days, which is almost three times a week.

All of these different sewage works add up. Cumulatively, the Wye received around a year and a half of sewage overflows in 2024, which helps to explain why, despite supposedly having the highest level of environmental protection from source to sea, its health was downgraded to “unfavourable, declining” by Natural England two years ago. Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water meanwhile has the worst record for leaky pipes of any company in England and Wales, with 171 litres of water being wasted by each household every day.

And, perversely, all this neglect does not come cheap. Welsh Water bills increased by 27 per cent in April, with the average metered customer now paying £575 a year, and are set to keep rising until the end of the decade.

The grim trilogy of pollution, crumbling infrastructure and ever-higher bills afflict every water company in England and Wales. Sewage works vented untreated waste into our rivers and seas 550,000 times across both countries last year, for a combined total of 500 years, and public anger is growing. Opinion polls suggest ordinary people have lost any trust in water companies to do the right thing, and suspect instead that this year’s higher bills will go straight into inflating their profits. “They never put any money in, they just take. They never maintain anything,” said Farnworth.

Everyone—from consumers to regulators to politicians to the water companies—agrees that the water system created at privatisation in 1989 is not working. The important question is why.

When Margaret Thatcher took office in 1979, state-owned companies employed 9 per cent of the UK workforce. Her government thought they were bloated and inefficient, and launched an aggressive drive to sell them off. She started by selling defence companies, before moving on to British Telecom, British Airways, Rolls-Royce, gas companies, airports, seaports, carmakers and others, marketing their shares to ordinary people in what the government said was a drive to democratise capitalism, and what her critics said was an orgy of profits for advisers in the City of London.

In its manifesto for the 1987 election, the Tory party promised more of the same: “It is no mystery why privatisation has succeeded. The overwhelming majority of employees have become shareholders in the newly privatised companies. They want their companies to succeed. Their companies have been released from the detailed controls of Whitehall and given more freedom to manage their own affairs.”

Water at the time was supplied (and sewage processed) by 10 large Regional Water Authorities (RWAs), each covering one or more river basins, plus a small number of private but tightly regulated water-only companies. The RWAs dated from 1974, when a hodgepodge of municipal, local, regional and other arrangements were rationalised into a single system. They dealt with everything water-related, from flood control and fisheries to drainage and water extraction.

Although this setup did provide 10 ready-to-sell entities, water was not an immediately obvious target for privatisation. Leaving aside ethical issues around whether an absolute necessity for life should be sold for profit at all, water is cumbersome and expensive to move, meaning that consumers would never be able to pick and choose between suppliers. Private companies would be monopolies in their areas, just like RWAs were, so they could not face the kind of competition that supposedly helps to discipline management and encourage innovation. Any investment that would be made—whether to reduce sewage spills or replace leaky pipes—would, if anything, reduce demand for the product. Water is almost the definition of a non-growth market, since no amount of marketing is likely to persuade people to use much more of it than they already do, and it was hardly likely that it could become a major export.

Still, after Thatcher won a third term in office, the environment secretary, Nicholas Ridley, stood up in the House of Commons to persuade his colleagues to back the sale of the RWAs. “Privatisation will, for the first time, give an incentive to innovation and efficiency and a new freedom to allow companies to follow the industrial logic of their own development both vertically and horizontally and to compete overseas,” he said.

The debate became bogged down in the usual back-and-forth about who exactly was to blame for everything but, as it wore on, Ridley made several interconnected arguments for why selling the RWAs made sense. The country’s water and sewage infrastructure was old and getting older, he said. By freeing water companies from Treasury control, they would have the freedom and funds to invest in the new facilities and new pipes necessary to provide a water system fit for the future. Meanwhile, the disciplining effects of the private sector would help raise standards and lower costs for consumers. In the private sector, the RWAs could expand beyond just supplying water, and become swashbuckling giants that could earn profits abroad and feed those profits back into supplying water at home. These would be British companies, owned by British shareholders, managed for the benefit of British people but operating globally.

At the time, Britain was nicknamed “the dirty man of Europe”, owing to the pollution flooding into its rivers and seas, with the Mersey estuary being particularly notorious as a grim cocktail of human and industrial waste. Public pressure was building to do something about this, and new European regulations imposed a legal duty on the government to improve the situation. Ridley’s water bill would therefore remove the RWAs’ regulatory role—including the monitoring of sewage discharges—and give it to an independent National Rivers Authority, which would have the power to fine the companies if they didn’t clean up. A separate Water Services Regulation Authority (Ofwat) would control the prices the new companies could charge and oversee their investment proposals, while a final regulator—the Drinking Water Inspectorate—would check that what came out of the taps was fit for human consumption.

“Gamekeepers should not be poachers as well,” said Ridley. “Those responsible for the treatment and disposal of sewage effluent should not also have the task of regulating pollution and prosecuting their own customers.”

Ridley’s bill passed parliament with ease—becoming the Water Act 1989—and within months the RWAs had become 10 independent companies. The £7.6bn raised by the sale of their shares on the London Stock Exchange helped to fund the write-off of their debts: they were unencumbered by the past, and ready to create a new and better future, with newly empowered regulators watching to make sure they did the right thing by their customers, their shareholders and the country.

It did not, however, work out that way. In October last year, the government convened a commission to ask why. “Something has clearly gone wrong when the largest water company in England [Thames Water] is struggling close to insolvency, when there are criminal enforcement cases in train against pretty much all water companies, when a number of companies’ debt is rated at below investment grade, and when over a third of water companies are formally challenging the economic regulator’s decisions,” said the commission’s chair, the veteran civil servant and former ambassador Jon Cunliffe, in a speech in Manchester in February.

Cunliffe asked members of the public for their thoughts. In eight weeks, from February to April, he received fully 50,000 submissions. “There is, rightly, a great deal of anger with where the system is,” he said. “I have met no one who is happy with the current system.”

At the time of privatisation, government ministers had a model in their heads for what Britain’s water companies would become, and it was French. Over the Channel, utility companies (the predecessors of what are now Veolia and Suez) not only supplied water and processed sewage, they also invested wherever they saw a return. In 1983, slightly improbably, the Compagnie Générale des Eaux even co-founded Canal+, France’s first pay-TV channel, and it proved a hit. Why couldn’t that happen in Britain, too? Why shouldn’t Severn Trent or Anglian Water go toe-to-toe with Rupert Murdoch?

Of course, they couldn’t be expected to transform themselves from cossetted, state-owned services to global utilities overnight, so for the first half-decade or so of their existence, the government kept a “golden share” that allowed it to overrule any takeover bids. It didn’t want those French heavyweights coming in and knocking out their British challengers before they’d learned how to fight.

And the water companies didn’t waste any time in bulking themselves up. Welsh Water and North West Water both acquired their local electricity companies; other companies invested in telecoms, hotels, testing facilities, construction companies and other water companies overseas. Ofwat, keen for the privatisation experiment to be a success, allowed average bills to increase throughout the 1990s. By the time the Tories lost power in 1997, Brits were paying a third more for their water, and they were not happy about it. The privatised companies were seen as greedy profiteers, perhaps epitomised by Yorkshire Water, which in 1995 paid out a £50m dividend to its parent company, despite Bradford at the time being at risk of running out of water during a hot summer. The CEO, Trevor Newton, invited the press to watch him wash with a flannel—“I personally have not had a bath or shower for three months,” he claimed—but failed to quell anger about what was seen as incompetence and profiteering.

The New Labour government slammed on the brakes. It imposed a windfall tax on all the privatised companies, which signalled a sharp change in approach. Average water bills stopped rising, and it became clear that many of the investments made in the early years had been disastrous. Welsh Water collapsed, only to be reborn as a not-for-profit company with nothing to show for the experiment but £1.8bn of debt. Deep-pocketed private investors swept in to buy up the chastened companies and, no longer subject to the transparency requirements of the stock market after they took them private, began to play the clever financial games of the early 2000s.

Macquarie—the Australian investment fund nicknamed the “vampire kangaroo”—bought Thames Water in 2006, before selling it on to investment funds from Abu Dhabi, China, Kuwait and elsewhere; Canadian and Australian pension funds took over Anglian; Yorkshire Water was bought by a consortium of banks, as was Southern Water; Northumbrian Water is owned in Hong Kong. The ambition had been for British water companies to be owned by British investors, run by British managers and listed in London; but only three of the original 10 still fit that model, and major foreign investment funds own significant chunks of their shares. The ambition had been to democratise capitalism, but instead the companies’ owners broke free from almost any constraints on their behaviour.

It’s possible to argue about why this happened, but the consequences are inarguable: the companies’ debt load exploded. By 2023, the water companies collectively owed more than £64bn in debt, having extracted dividends of more than £77bn, which meant they had paid themselves not only every penny that the companies had borrowed since they were listed on the stock exchange but much of what they owned beforehand too. “Since privatisation, shareholders have literally invested less than nothing,” wrote David Hall of the University of Greenwich in a report for the trade union Unison.

Privatisation was supposed to bring investment in the nation’s infrastructure. But instead of being paid for by the company shareholders, that investment has been paid for entirely from what was left from customers’ bills after the owners had taken their dividends, which means it has been completely inadequate. The National Audit Office estimated this year that if the process of replacing worn-out water pipes continues at the current rate, it will take 700 years for the task to be completed.

In the original conception of privatisation, companies would borrow to invest, just as an ordinary person takes out a mortgage to buy a house. In reality, however, their borrowing has been more like maxing out a credit card, then taking out new credit cards to pay it off. The debt has kept increasing, and maintaining it has wiped out an ever-larger share of the companies’ earnings.

Ofwat has finally woken up to what has happened but seems frozen by the scale of the challenge that now confronts it. It first raised its concerns about Thames Water—which now owes around £20bn—three years ago, but since then rating agencies have downgraded the company’s debt from BBB to C, deep into what is called “junk” territory, making it almost impossibly expensive to refinance. This is an extraordinary predicament for a utility with a captive market and completely predictable revenue stream, but a logical consequence of the short-termist way it has been run.

“People say, ‘Oh, the problem is that these are really badly run companies,’ but they’re not: they’re brilliantly run companies,” Hall told me. “They extract every possible penny from the economic context in which they find themselves, and they’ve generated terrific returns for their owners, who are also known, misleadingly, as investors.”

The water companies themselves do not accept that they are to blame for the situation, and prefer instead to blame Ofwat, their regulator, which does indeed have a strange role in this whole fiasco. Because the water companies are not able to compete with each other in a normal way, owing to the fact that customers have no choice which one they buy water from and send sewage to, Ofwat steps in to simulate the pressures of the open market with a self-generated algorithm of such complexity that I have never met anyone who even pretends to understand it. It tells companies how much they can charge and instructs them on how much to invest, often to their managers’ great displeasure.

“Many of our assets are older and we believe there should be more money directed towards maintenance, capital maintenance and renewals. That does hold us back a little bit. Clearly, there has to be more investment,” Ian McAulay, chief executive of Southern Water, said in evidence to parliament’s Environmental Audit Committee in 2021.

I am sure that McAulay is an honourable man, and there isn’t any reason to doubt he is as personally appalled as he claims to be, but he only joined Southern Water after it was caught illegally dumping sewage in the sea on a catastrophic scale. It was fined £90m in 2021 for what was at the time the most egregious offence committed by one of the privatised utilities, and it’s quite clear the previous management did not share McAulay’s enthusiasm for investment, not least because it halved contributions to its pension scheme so it could pay a special dividend to its private equity owners.

Squeezed between Ofwat’s refusal to allow them to raise bills, and their owners’ desires for ever more cash, the water companies’ managers had to look around for savings, which explains why investment has been so woefully inadequate in the years since privatisation. Sadly, governments have made that easy for them. An estimated three billion litres of drinking water is lost daily through leaky pipes, at a huge financial and environmental cost, and regulators have for decades done little if anything about it.

And then there’s sewage. In 1996, the new National Rivers Authority was folded into a single Environment Agency (EA), which is tasked with making sure the water companies are actually cleaning the sewage, rather than just letting it pour into the rivers and the sea (in 2013, Natural Resources Wales took over the regulatory role on the Welsh side of the border). Governments in London and Cardiff have progressively made it harder for the regulators to do this job, particularly after 2010, when funding for the EA’s environmental work fell by two-thirds, to just £40m, leading to a decade-long squeeze. “Some people can no longer afford to work for us,” said James Bevan, at the time chief executive of the EA, in evidence to parliament in 2023. “Some of our staff are using food parcels. I think that tells you a lot.”

It was all part of a light-touch approach to regulation which allowed the water companies to cheat and ensured there was no one to catch them. You might call it legalisation through under-enforcement. From 2009, they were allowed to “self-monitor” their own compliance with environmental standards in a grimly ironic return to the system of poachers as gamekeepers that the entire privatisation process had been intended to put an end to. The consequences were predictable.

Sorting out the mess that is the water sector will be complicated, controversial and ruinously expensive

In the latest published results, none of England’s rivers were rated as “good” or “high” under the Water Framework Directive, with more than half of them failing because of sewage pollution. Academics studying seaweed in the Mersey estuary report that sewage levels have returned to levels last seen in the 1980s.

This was obvious to the EA’s inspectors, but their ability to take action was further limited by the 2015 Deregulation Act, which obliged them to promote economic growth, alongside their usual duties. If your job is to stop pollution but you know that letting people pollute increases gross domestic product, what are you supposed to do?

“That obligation to promote economic growth was quoted at us again and again, particularly if we wanted to take enforcement action against a company or group,” one former EA manager tells me. “But the [Mersey] is on its arse, so suddenly the politicians have got to engage. It’s only since it turned green and there’s nothing living in it that they’ve all gone ‘Oh, shit.’”

You can see why the politicians did not want to engage: sorting out the mess that is the water sector will be complicated, controversial and ruinously expensive. For decades, the companies’ owners have extracted billions of pounds that should have been invested in plugging leaks and treating sewage, and sent the proceeds to parent firms overseas. Macquarie took more than a billion pounds out of Thames Water during the 11 years in which it held a stake in the utility, a period when the company’s debt level almost doubled to £11bn. In 2022, Anglian Water announced a £65m package to help vulnerable customers, while also paying £92m in dividends to its owners, which included the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority. That same year, it was rated England’s equal worst-performing water company by the EA, because of a terrible record of serious pollution.

It was public pressure that finally forced action. People got so angry with the state of their local rivers that they coalesced into multiple pressure groups—Friends of the River Wye, Windrush Against Sewage Pollution, the Ilkley Clean River Group, Oxford Rivers Improvement Campaign and many others—under the unofficial leadership of former popstar and Undertones frontman Feargal Sharkey, who just wanted to go fly-fishing but found himself instead taking the EA to court over the state of the River Lea.

A retired professor, Peter Hammond, meticulously analysed data released by the water companies and conclusively proved that they were systematically dumping far more raw sewage than they were allowed to. Swimmers, surfers and others—including three members of the 2024 Oxford University rowing squad—reported that they had vomited after accidentally drinking water while exercising. Even Lake Windermere is not the pristine water body it once was.

In 2021, Ofwat opened an investigation that eventually examined all the water companies in England and Wales, and last year fined three of them a total of £168m. In May, the EA announced it had opened 81 criminal investigations into illegal dumping of sewage, with managers facing up to five years in prison if found guilty. And in February, Ofwat said it was forcing the water companies to invest £104bn in improving their facilities, a near-doubling of expenditure compared with the previous five-year period.

This is all welcome, and long overdue, but it’s also a sign of how badly successive governments have handled this crucial industry. Water supply and sewage treatment are the ultimate long-term undertaking. Pipes and sewage treatment plants last for decades, and need therefore to be carefully planned to take account of population growth and climate change.

Instead, however, politicians have acted like indulgent but neglectful parents. They’ve ignored the water companies for years and now, finally embarrassed by their antics, have given them a slap. The trouble is that there’s no reason why the companies’ owners should stick around now that the easy dividends have stopped flowing. That would leave someone else with the responsibility of clearing up the mess they’ve left behind.

In June, Cunliffe published the interim results of his review into the water industry, recommending that the government adopt a long-term strategy; that the rules around water be simplified and the regulators better resourced; that more work be done to understand the state of the nation’s infrastructure; and that we need patient, long-term investors who can count on a predictable and stable environment. This would, he said, require new legislation.

“We have heard of deep-rooted, systemic and interlocking failures over the years—failure in the government’s strategy and planning for the future, failure in regulation to protect both the billpayer and the environment and failure by some water companies and their owners to act in the public, as well as their private, interest,” he said.

What is particularly dispiriting is that his proposals appear to be aimed at solving the same problems privatisation was intended to resolve three decades ago, except now with less money, older infrastructure and more debt. We have been running hard for years, only to discover we were going in the wrong direction.Now we have to slog all the way back to the starting line before we can make any progress at all.