On a spring day in 1984, a shocking message came across Usenet, a messaging service that acted as the town square for the nascent internet: “well, today, 840401, this is at last the Socialist Union of Soviet Republics joining the Usenet network and saying hallo to everybody.” The author proposed a discussion with the US and Europe about “peaceful co-existence” between the Cold War rivals and encouraged a toast with vodka. It was signed by Soviet leader Konstantin Chernenko and originated from a machine named “moskvax,” implying a Digital Equipment VAX minicomputer—a powerful machine used by many US universities as their gateway to the internet—located in Moscow. That the Soviet Union would connect to the internet at the height of the Cold War, when information from the western world was smuggled in as samizdat, seemed impossible. That the United States, which had financed the computing network, would permit a Russian connection, seemed even less likely.

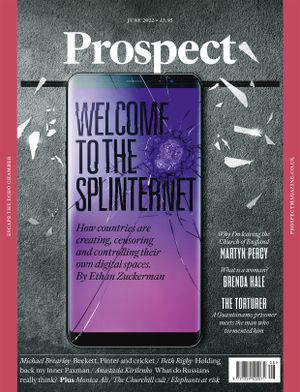

The Kremvax hoax, as it came to be known, was an April Fools’ joke played by Dutch internet pioneer Piet Beertema. Thirty-eight years later, as Russia’s war against Ukraine has shattered whatever “peaceful co-existence” reigned between Russia and Nato allies, it’s worth reflecting on Beertema’s prank. This time around, Russia seems determined to leave the global internet and build its own sovereign internet, or “splinternet.” But as with many of the plans announced by Vladimir Putin, the reality is much more complicated: Putin’s plan may be as fanciful as Chernenko’s Usenet post.

Many internet users in 1984 found the Kremvax hoax believable because it was, then as now, shockingly simple to connect computers to the early internet. Despite the network’s origins as a US Department of Defense research project, the actual operations of the internet were almost entirely decentralised. Any administrator of an internet-connected computer could invite another computer online by connecting the machines via a phone call. Indeed, two years before the Kremvax hoax, Stockholm University did just that, allowing Soviet scientist Anatole Klyosov to participate in a “world computer conference” conducted online by the World Academy of Art and Science. Connecting Klyosov to the internet was the easy part for his Swedish hosts—getting him access to a computer and a modem was the challenge. From 1982 through to 1987, Klyosov—the USSR’s only internet user—travelled daily to Moscow’s Research Institute of Applied Automated Systems, the sole location in the Soviet Union that had a computer he could use to explore the internet developing beyond Soviet borders.

At a moment where the phones most of us carry are internet-connected computers, it is vastly easier to connect people and devices to the internet than it is to disconnect them. More precisely, it is hard to detach either a nation’s networks or society from the global internet and expect either to keep working well. Yet this is Putin’s declared intention. Russian newspaper RBC Daily reported in July 2021 that the nation had conducted a month of tests of a “sovereign internet” and that Russia’s network had been “physically disconnected” from the global internet during the trial.

Yet experts are sceptical that Russia actually disconnected. Global internet traffic is closely monitored by private companies and academic researchers, and major observatories registered no significant change in Russian internet traffic during the month of the purported test. At Tufts University, cybersecurity professor Josephine Wolff noted that “whatever Russia did [that] summer, it did not physically disconnect from the global internet.”

China’s Great Firewall works in part because most users aren’t trying to evade it

In another sense, Russia’s internet is as isolated as it has been at any time since 1987. A new disinformation law passed by the Russian Duma in March sharply increased penalties for spreading “false” news online, which includes referring to the invasion of Ukraine using terms other than the preferred terminology of a “special military operation.” Facing threats of 15-year jail terms and crippling fines, independent journalistic outlets like radio station Echo Moskvy have shut down while others, like Meduza, have relocated to Latvia or other neighbouring countries.

Russia may have silenced some of its most independent voices, but can the Kremlin really create a domestic internet that precludes criticism of the regime? One where all reachable websites, including social media, will be hosted in Russia and subject to local content controls? And even if it can pull off the technical feat, will its internet users, long accustomed to international connectivity, tolerate a rapidly closing online world?

No filter

As countries around the world connected to the internet, governments in societies like Saudi Arabia faced a novel set of challenges. Saudi print media was already highly controlled, with domestic outlets forbidden from reporting on sensitive topics. International media was routinely censored to eliminate content incompatible with its version of Islamic law, which includes portrayals of homosexuality or revealing images of men and women’s bodies. The internet suddenly made available a flood of uncontrolled information, including pornography, political dissent and criticism of Islam.

The ruling monarchy sought to control the internet in much the same way as the network administrator at a primary school might when putting in place a filter to keep children from surfing porn. In Saudi Arabia, this filter is maintained by the Communications and Information Technology Commission, a national body controlled by the House of Saud. The filter blocks an estimated 500,000 websites. At the same time, most popular social networks are accessible, though accounts from individuals critical of the government are sometimes blocked. The Saudi government also routinely pressures online providers to remove content it finds offensive—in 2019, Netflix agreed to remove from its Saudi service an episode of US comic Hasan Minhaj’s series Patriot Act that discussed the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

These two techniques—a national--level content filter, and government pressure on international media companies—are the heart of the digital censorship strategies used in most of the 21 countries that human rights charity Freedom House categorises as “not free” in internet terms. This sort of censorship is understood to be “leaky”: users in Saudi Arabia and other censored countries routinely use certain tools, designed to protect internet traffic from surveillance from the state censor, to access blocked sites. Other prohibited content comes from material shared on social media.

Censorious governments face a tricky balancing act in tightening their filters. Too tight and it becomes difficult to conduct ordinary business. Bahrain blocked access to Google Earth in 2006 when activists began using satellite imagery to illustrate that much of the island’s land was allocated to estates for the ruling family while many Bahrainis live in overcrowded neighbourhoods. When activists began circulating (via email) illustrative images as a PDF document, Bahrain dared not block PDF files for fear of shutting down legitimate business communications.

Shutting off popular services can also impel users to install tools like virtual private networks (VPNs) to evade censorship. Tunisia, under the autocrat Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, began blocking popular video-sharing sites in 2007, and escalated to blocking Facebook in 2008. Activists launched a campaign to encourage Tunisians to install VPNs and join Facebook en masse, and the population of Tunisian Facebook users actually grew during the blockage. Ben Ali’s government responded by implementing a much more sinister tactic: for a few minutes each hour, the Tunisian internet authority redirected the Facebook login page to a phishing page, allowing the government to capture the passwords of many domestic Facebook users. The net effect was to intimidate them and limit political speech on the platform.

Ben Ali was right to fear the power of Facebook. Videos of protests that erupted in the city of Sidi Bouzid in December 2010 spread on the platform and were rebroadcast by Al Jazeera and other pan-Arab networks to viewers across Tunisia. The resulting national wave of protests toppled his government and launched the Arab Spring.

These events have been carefully studied by Chinese internet authorities, which have taken a far more complex approach to internet censorship. China’s system of internet filters, colloquially called the Great Firewall, is vastly more sophisticated than the simple filters historically used by Saudi Arabia, Bahrain or Tunisia. Not only does the filter block blacklisted sites, it is also able to detect internet traffic likely to be from a virtual private network or another tool used to circumvent censorship. This service relies on “deep packet inspection”—examining the contents of individual data packets that cross through Chinese internet routers, rather than simply blocking packets from a specific internet address—and machine learning, which can detect novel techniques to evade censorship. In other words, not only can the Great Firewall block access to websites—it can detect efforts to “hop the firewall” and access those sites, and disable these attempts even when they use novel methods.

An example of the Russian internet’s chaotic past is VKontakte, a social network modelled on Facebook

The Great Firewall also uses a technique called DNS hijacking. DNS is the internet’s phone book—when you want to visit prospectmagazine.co.uk, DNS is the system that tells your web browser that Prospect’s server lives at a specific IP address (13.248.179.26 at last check). Rather than maintain a single, central directory, there are tens of millions of servers around the world that can look each other up if they don’t know how to resolve a particular domain name. The Great Firewall includes Chinese domain name servers that deliberately don’t know how to resolve popular domain names, including wikipedia.org or google.com. If you were to try pointing your computer to an unpolluted domain name server outside the country (like Google’s 8.8.8.8), your request would be hijacked and re-routed to a Chinese domain name server.

While the Great Firewall is sophisticated, the key to its success is more social than technical. The Chinese government has invested billions in domestic businesses that provide Chinese users with most of the services they might seek out on US or European-hosted servers. While Tunisian users were desperate to access Facebook, Chinese users are more likely to seek out Sina Weibo, Weixin or Youku, all hosted within China and subject to local oversight and restrictions. These services are vibrant, widely used and generally better suited to the needs of Chinese internet users than foreign competitors—many Chinese social media tools have functions built in that allow users to hail a cab or buy a pizza through the local equivalent of Facebook.

As a result, the Great Firewall works in part because most users aren’t trying to evade it. In 2014, internet scholars Harsh Taneja and Angela Xiao Wu published a paper titled “Does the Great Firewall Really Isolate the Chinese?” They argued that most web users worldwide gravitate to content in their own language and consonant with their own interests. We might expect Argentine internet users to seek out content in Spanish or to frequent football sites, and we shouldn’t be surprised to see users in the Arab world seeking out Indian websites for Bollywood movies, which are extremely popular in the Middle East. Using this same logic, they argue that there are likely few Chinese users desperately seeking access to the BBC’s website—they are more likely to be seeking domestic content in their “culturally defined market.” The paper is consistent with research that I conducted at Harvard’s Berkman Center with my colleague Hal Roberts on internet circumvention tools in 2010. At that point, we estimated that fewer than 3 per cent of internet users in heavily censored countries used VPNs or other tools to evade restrictions.

From censorship to splinternet

Because traffic to many international sites is blocked, and because most Chinese people are users of domestic search, social media and videostreaming services, most Chinese internet traffic is domestic—it is routed between Chinese internet service providers (ISPs) and never transits across the global internet. This is not the case for most countries—an Italian web user reading a webpage from an Italian newspaper might well have her internet packets routed through Europe or even the US. Since so much web traffic is domestic to China, and because no international telecommunications companies provide competitive services there, it is possible the country could disconnect from the global internet with little impact on most of its population.

Internet experts warn of a forthcoming “splitting of the root.” The Domain Name System, the internet’s phone book, relies on 13 “root servers.” These servers are the ultimate authority for finding other DNS servers, and they are hosted by academic, commercial and non-profit organisations around the world. Rob Knake, director of cybersecurity for the White House during the Obama administration, predicts that within the next decade China will stop using the root servers relied on by the rest of the world and transition to its own. Those servers, he speculates, might choose not to recognise any websites that end in .tw (Taiwan’s country code), or to implement any other restrictions China finds geopolitically convenient.

When Russian authorities announced their plans for a sovereign internet, they were likely experimenting with making similar changes. Russia’s test might have involved routing nameserver traffic through Russian servers, rather than using the global domain name system. So long as these new Russian phone books maintained accurate data about the location of sites hosted in the US or Europe, it’s possible, at least for now, that it could have conducted a successful test which might have gone undetected by monitors.

But could Russia run a successful splinternet? The Chinese example suggests that at least two things are necessary to build a successful local internet: domestic internet tools, and linguistic isolation. Two of Russia’s most popular social media platforms—VKontakte and Odnoklassniki—are hosted within the country, and owned by Mail.ru, a popular email service and internet portal. But international sites remain popular with Russian internet users. According to Similarweb, which tracks web traffic globally, Google is the second most popular website in Russia as of March 2022, and YouTube the third. Wikipedia, which Russia’s internet regulator Roskomnadzor has threatened to fine unless the site removes content about the war in Ukraine, is the 12th most popular site in Russia. It is unclear that Russian users would be satisfied with domestic alternatives like RuTube, a YouTube clone hosted by Gazprom Media, which Similarweb ranks as the 74th most popular site in the country.

In late March 2022, a Russian court banned Facebook and Instagram on the grounds that they were “carrying out extremist activities,” while Meta’s WhatsApp was permitted to continue operating because it was a “means of communication, not a source of information.” Earlier that month, Russia had restricted access to Facebook in response to the platform’s decision to ease hate speech restrictions on posts advocating violence towards Russian invaders in Ukraine.

What’s unclear is whether these blockages are actually effective. Kevin Rothrock, managing editor of the English language edition of Meduza, an independent news website focused on Russia, reports that the site continues to enjoy heavy traffic despite being blocked within Russia. “Our traffic is what it was before the war. It surged during the first weeks of the invasion, and has now fallen back to where it was before the war, possibly as the block has kicked in.” Meduza operates from Latvia to evade Russian restrictions. Its core staff are alumni of independent news site Lenta.ru, which was targeted by the authorities in 2014 for publishing an interview with a member of the Ukrainian nationalist party Right Sector. Rothrock notes that the site’s primary readership is Russian-speaking, and that the site mainly serves Russians in Russia, and continues to do so today.

“Russian ISPs haven’t fully instituted these blocks,” Rothrock explains. “It’s either incompetence, or lack of equipment. Some people can reach us directly through their ISPs. Some are using VPNs.” Rothrock pointed to a report from Russian news agency RBC, which contracted research firm Mediascope to track traffic from Russia to major online platforms in the first three weeks of the “special operation.” Traffic to Instagram fell from 39m users a day to 34m users a day—a significant dip, but hardly the plunge a full blockage would create.

Why can’t Russia block?

While China’s internet has been built from the ground up for censorship, control of the Russian digital sphere has a more complex history. Scholar of the Russian internet Gregory Asmolov has explained that “the Russian internet is the only internet that started as a totally free space—to some extent even less regulated than the western internet—and developed into one of the most regulated and restricted internet spaces. That’s why, unlike other internet spheres that haven’t experienced such a dramatic change, it’s full of contradictions between different logics.”

An example of the Russian internet’s chaotic past is VKontakte, a social network modelled on Facebook. “It wasn’t only a social network but also a mix of 4chan, Napster and Pornhub. It offered an unlimited opportunity to host and share music and video files, including pirated full-length movies and pornography,” notes Asmolov. “Imagine a network that combined the reach of Facebook with some elements of the darknet [a portion of the internet often used for buying and selling illicit goods]—that was VKontakte to the Russian-speaking world.” The network has cleaned up significantly—in both laudable and less salutary ways—since its founders, brothers Pavel and Nikolai Durov, left the project and Russia itself and created Telegram, a messaging service that is a critical part of the media landscape in Russia and Ukraine.

Raised on freewheeling spaces like VKontakte, Russian internet users may not be as satisfied with a domestic network as Chinese users have been. And the Russian internet is not as easy to control from a technical standpoint as China’s. Internet service providers purchase the connectivity they sell to their customers from backbone providers, companies that maintain massive data pipes that carry traffic around the globe. The Chinese internet channels all traffic to international websites and services through a small handful of internet connections controlled by telecommunication providers China Telecom, China Unicom and China Mobile. These three providers “peer”—exchange traffic—with global backbone providers at a small number of internet exchange points (IXPs). China can surveil and control international traffic by filtering the content carried by these three companies and can disconnect China from the global internet by severing these few peering relationships, an architecture that led Dave Allan, a researcher at tech multinational Oracle, to observe that “China could effectively withdraw from the global public internet and maintain domestic connectivity (essentially having an intranet).”

Russian ISPs, on the other hand, connect to the global internet in many more places, a legacy of the country’s rapid and chaotic connection to the rest of the world at the end of the Cold War. Russia’s largest IXP connects 500 -different domestic internet service providers to each other and to the global internet, and six other IXPs connect yet more ISPs. To force Russian ISPs to block Instagram and Facebook, Roskomnadzor has to ensure each ISP is individually -blocking connections to the banned sites. To disconnect Russia from the global internet, thousands of peering relationships between Russian ISPs and global backbone providers would need to be severed.

The reality of Russia’s splinternet is both more and less than what Putin’s administration has promised

An interesting test of Russian internet resilience happened when the CEOs of global backbone providers Lumen and Cogent both announced that they would cut services to some Russian clients in order to prevent cyberattacks. Despite speculation that Russian internet traffic would struggle to squeeze onto the remaining connections, internet monitoring group ThousandEyes reported on 10th March this year that “backbone internet connectivity to and from Russia does not appear to be limited or constrained despite recent reports of major global transit providers ‘disconnecting’ from Russia. Russia’s connection to the global internet continues, enabling traffic to flow into and out of the country—at least at an infrastructure level.” Despite two major providers disconnecting, the thick mesh of connections between the Russian internet and the rest of the world absorbed the traffic surge without any apparent hiccup.

While Russia may not have succeeded in disconnecting its splinternet, and while some Russian users can still reach “banned” sites like Meduza without VPNs, one form of government disconnection has succeeded. Rothrock explained that Russian government websites have begun blocking connections from US-based internet addresses. “Often I have to use a VPN to see what Kremlin.ru is saying,” says Rothrock, who researches Russian sites from his home in New Haven, Connecticut.

Other forms of disconnection are less dramatic than a splinternet, but still significant. Blocked websites are now delisted in Yandex, Russia’s leading search engine, making them harder for Russian users to find. But not all these disconnections have been triggered by the Russian government. When Visa and Mastercard cut Russian citizens off from their payment platforms, Russians who hosted content on servers in other countries—including dissident journalists—lost their ability to pay their international hosting bills. The Internet Archive stepped in to help radio station Echo Moskvy preserve its published -material.

The future splinternet

The reality of Russia’s splinternet is both more and less than what Putin’s administration has promised. Russia has not yet, and may never, sever its domestic network from the global internet. Thus far, Russia’s splinternet looks like a Potemkin village, a painted fiction with no real substance. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov admitted to a Russian journalist that he uses a VPN to access blocked sites, noting: “why not? It’s not banned.”

Yet it’s too early to be confident about the failure of Putin’s sovereignty project. When the rest of the world participates in a blockage, national services can often catch up fast. Mir, a Russian payment provider launched in the wake of sanctions that followed the Kremlin’s 2014 -incursions into Ukraine, has surged in popularity as Visa, Mastercard and -PayPal have pulled out of the country. Should the major tech platforms choose to stop providing service to users in Russia, it would almost certainly benefit Russian rivals like Rossgram, a hastily launched alternative to Instagram.

The leaders of open societies tend to assume that there’s a deep desire for accurate information in closed states. Hillary Clinton’s State Department poured funding into censorship circumvention tools, expecting a vast wave of dissidents in Cuba, China and other censored countries to seek out uncensored American information. The presumption that people want unfiltered information may, unfortunately, be flawed. Research on mis/disinformation suggests that readers even in democracies gravitate towards news that meets their preconceptions, rather than challenges their opinions. We may be less interested in the truth than in our truths. The sad reality is that anti-censorship efforts can work technically but fail based on lack of interest.

Angela Xiao Wu, whose research suggested that anti-censorship efforts aimed at China might fail due to China’s production of domestically popular content, reports that international news is now making its way into China in disturbing ways: “on the Chinese web, an enormous amount of mis/disinformation on world politics (esp US politics), health issues (esp in the past few years), and so forth builds on ‘translations’ of English content that itself is misinformation… To the Chinese eye, there’s even fewer (most times, none) contextual factors to judge the translated info. And both political and commercial (for traffic) actors utilise (mis)translation and problematic translated content for their own gains. In the end we see discussion about non-Chinese societies and news everywhere on the Chinese web, but it can appear to be an alternate universe.”

Rothrock has expressed a similar concern: “Russian people on Instagram are not on the platform to get the truth about Ukraine. Russian influencers are unhappy with the war and about losing contact with the west, but you can also find content about their culture being under attack in the west.” The sort of limited connections to international content that occur under censorship might lead to a similar situation as the one Wu describes—the circulation of mis/disinformation that supports narratives of Russian culture under attack, rather than information that contradicts the state.

Asmolov suggests we understand Putin’s attempts at a sovereign internet as part of a larger plan to create a “disconnected society.” Putin may have decided that it is “impossible to protect the internal legitimacy of the current leadership and keep citizens loyal if Russia remains relatively open and linked up to the global networked system,” he writes. This push towards disconnection comes at a moment when other previously open societies seem to be shifting towards authoritarianism. Should Putin’s splinternet come to pass, it might signal to other nations that are experimenting with internet controls that they should take further steps to disconnect.

India, despite its status as the world’s largest democracy, has been one of the most profound censors of the internet, cutting Kashmir off for months at a time and shutting down mobile data networks to try and quell farmer protests in New Delhi. Modi’s government has proposed sweeping rules to filter and control social media, and is nudging Indian users to domestic platforms hosted in local languages, perhaps seeking to replicate China’s splinternet. The language of sovereignty proposed in Russia, combined with a desire for an internet “decolonised” of western influence, may point towards a future in which national splinternets are the norm, not the exception.