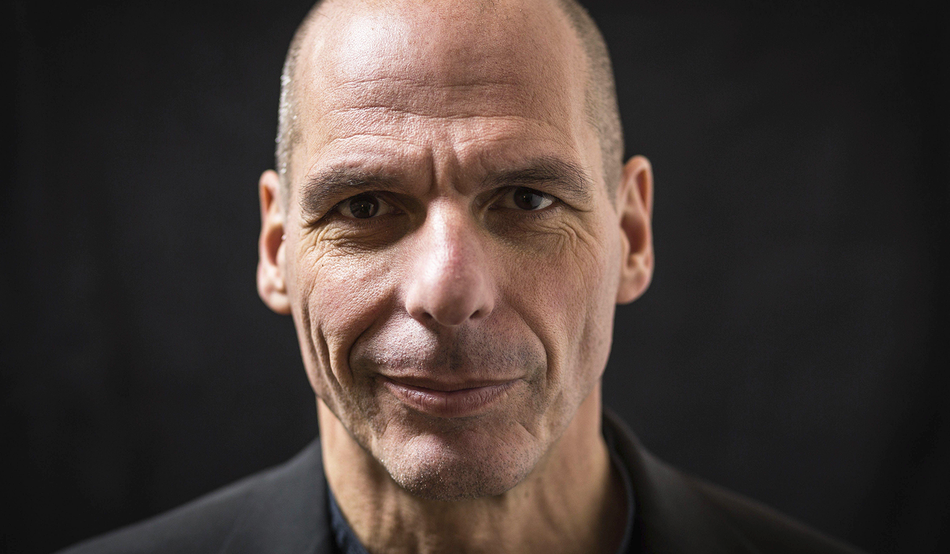

Yanis Varoufakis recently went through a “low period”. At times, he even calls it depression. The former Greek finance minister is not known for introspection, having swaggered onto the political stage during the Eurozone crisis, riding a motorbike in his trademark leather jacket. He brought irreverence and pluck to his battle against the proponents of austerity in Brussels. Even the eventual capitulation of his Syriza government to its creditors has not deterred him from passionately contributing to public debate.

But over the last few years, personal and political events—the war in Ukraine, the genocide in Palestine and defeats suffered by the left in Greece—took a toll. “For the first time in my life, I started feeling the weight of these defeats on my shoulders,” he tells me over video call. “When I get depressed, I write.”

The result is Raise Your Soul: A Family History of Resistance, a less polemical book than his previous works. To discipline his more academic tendencies (Varoufakis is currently professor of economics at Athens university), he frequently “writes books as if they are long letters to real people”, having previously addressed a history of capitalism to his daughter and a treatise on techno-feudalism to his late father. But during the pandemic he started feeling “extremely remorseful... where was my mum? She was my political mentor!”

Raise Your Soul begins with her story, then continues with the narratives of four other women in his extended family, which take us from Nazi-occupied Greece to British colonial Egypt and the violence of modern politics. Towards the end of the book, Varoufakis recounts how his wife, the artist Danae Stratou, physically put herself in between him and a group of “thugs” attempting an apparently political motivated attack. The book “was never intended to be a feminist history, but it ended up being [one],” he tells me. “I’m not sure that a man can write a feminist history... I don’t even know whether I have the right to appropriate the voices of women.”

“But, then again,” he says, “these women would simply be lost to oblivion if I didn’t write their stories. They cannot tell their stories because I’m the only one who remembers them.” He pauses our conversation to rifle around his overflowing desk, attempting to locate his mother’s diaries. Lost in accumulated history, Varoufakis looks a little older than I remember him on television, yet he is still sharp as a tack.

When it comes to engaging with other men (“the defective sex”), he has no time for puritanism. Recalling the Unite the Right anti-immigration marches through London in September, he argues that the left should not abandon angry young men. “I do not want to let any of them go to the fascists,” he says defiantly.

He points to his maternal uncle, whose journey from Nazi sympathiser to militant freedom fighter is charted in the book. His uncle “demonstrate[d] the worst and the best in humanity,” he says, but his mother taught him “not to be relativist” about her brother. “Fight him when he’s being a cad and take him to task when he’s lured to fascism, and at the same time you have to appreciate his qualities. If we can imagine doing this in the political sphere, I think humanity has a chance.”

It is only when I mention one of the precipitating events of his “low period”—Russia’s war in Ukraine—that our conversation turns a little tetchy. The conflict isn’t mentioned in his book and, when I ask whether he sees parallels between Ukraine and Greece’s antifascist struggle, Varoufakis’s response is there are “fascists on both sides” of the Ukraine war.

While Ukraine’s Azov brigade, for one, has far-right origins, Russian propaganda vastly exaggerates the number of Ukrainian fascists to justify Putin’s dubious campaign of “de-Nazification”, and Varoufakis seems to be echoing Russian talking points. He calls Vladimir Putin a “beast”, though, whose crimes he has campaigned against since 2001. This, he claims, caused him to be “pinpointed by the liberal press as being eccentric... back then, Putin was the blue-eyed boy of the west.”

But against the celebration of Greek and Egyptian anti-imperial resistance in his book, depicting the Ukraine war as “pointless” seems oddly ambivalent. Indeed, it seems reminiscent of the “relativism” his mother deplored.