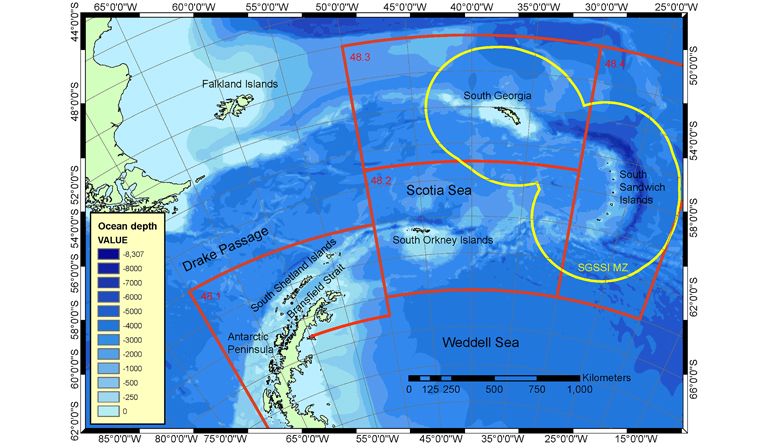

The UK Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (SGSSI) lies in the remote expanse of the southwest Atlantic, more than 1,000 miles from the southern tip of South America. Almost devoid of human inhabitants, the area is famed for its globally important concentrations of seabirds and marine mammals, fish and unique seabed communities of benthic organisms. The Territory is possibly the UK’s most significant biodiversity hotspot, home to around 95% of the global population of Antarctic fur seals and around 50% of the global population of southern elephant seals. Sperm, humpback, fin and other whales are increasingly present in the waters of SGSSI. The islands are also home to the largest penguin colony on Earth, with more than a million chinstrap penguins. The little-explored South Sandwich Trench is one of the deepest parts of the ocean, whilst elsewhere the seabed includes unique hydrothermal vent communities which remain little known and little studied.

However, this jewel in the crown of UK biodiversity is under threat, as climate change increasingly warms the waters around the islands, with glaciers now in retreat. Industrial fishing for Antarctic krill is also increasing with the potential to disrupt important ecosystem processes. Yet, as part of a 2023 review process, the UK has an opportunity to increase protection, by designating large portions of the waters around SGSSI as a fully protected marine reserve. This would safeguard whales, penguins and the other important species. This decision would also help the UK honour its commitment to the global goal of protecting 30% of the ocean by 2030 (the “30×30” target), of which the UK is one of the leading champions. Enhanced protection would help build resilience to the accelerating impacts of climate change, and better control fisheries for krill.

The Territory was formed in 1985, but UK interests go back much further in time, first to the islands’ discovery, and then to the claim made by Captain James Cook in 1775. Britain has controlled South Georgia for 250 years, seeing it become the epicentre of hunting in the Antarctic. First, Antarctic fur seals were targeted, then southern elephant seals, and finally, during the twentieth century, the great whales, with their virtual extermination. By the latter half of the twentieth century, fishing for finfish and Antarctic krill had also begun, even though krill remains a vital food-web link in the Antarctic and the primary prey for many species of baleen whale, seal, penguin and fish. Under UK governance, the wildlife of SGSSI has been exploited, taking some species to the edge of extinction; but today things are changing.

Today, hunting for whales and seals is banned and many other ecosystem risks are well-managed, including through a ban on destructive bottom trawling, and a closed season for the krill fishery during critical breeding and feeding periods for krill-eating predators. There are also a number of closed no-take zones where fishing is completely prohibited.

A Marine Protected Area (MPA) was first designated in SGSSI waters in 2012. At that time, it was at the cutting edge of marine management, but now governments are under greater scrutiny. Scientists recognise that much more is needed to sustain long-term ocean health, which is why many governments – including the UK – successfully advocated for the 30×30 target to be included in a new Global Biodiversity Framework, agreed at a meeting of the Convention on Biological Diversity last December. With such strong support for 30×30 from the UK, and a review of the SGSSI MPA taking place in 2023, it’s time for tough questions and urgent decisions. At present only 23% of the MPA is fully protected from extractive industries, so more is needed to bring SGSSI closer to modern standards.

Of the species commercially harvested in SGSSI waters, krill is the most significant. The krill fishery is managed by the international Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), with more stringent management imposed by the UK within the SGSSI MPA. Currently, the krill fishery operates only in the Scotia Sea (see map), but catches are increasing, with 2020 seeing record catches (450,781 t).

A key reason for increasing protection in SGSSI waters is that, since whaling was banned, many whales have returned to these waters. First, southern right whales were seen, and then humpback whales, which are now probably close to pre-exploitation numbers. More recently, there are signs that fin whales and blue whales have started to return. Increased protection in the waters around the islands would offer umbrella protection for the whole ecosystem, including large numbers of baleen whales, beaked whales and killer whales, some of the largest aggregations of penguins on the planet, as well as fish, zooplankton and important deep-sea communities.

South Georgia remains an area of important economic interest. Nevertheless, managers can ensure that ongoing fisheries are sustainably managed whilst aiding the recovery of baleen whale populations by the creation of pelagic fishery no-take areas around South Georgia.

In contrast, the South Sandwich Islands are remote and unattractive to the krill fishing industry, so remain of low economic interest – for now. However, a recent scientific survey has shown a considerable biomass of krill exists around the islands. One solution for protecting the area against any future krill fishing would be for the UK to work within CCAMLR to close the waters around the islands and create a large no-take zone. However, given the realpolitik -currently paralysing CCAMLR, and its failure to designate any new MPAs since 2016, a more realistic option is for the UK to designate the South Sandwich Islands as a national no-take marine reserve.

Now is the time to “future proof” these special islands and surrounding seas, while we still have the chance. Protecting biodiversity in the Southern Ocean following the industrial destruction of the past would be a welcome and achievable aspiration for the UK, especially given the powerful control it once exerted over shore-based whaling in the Scotia Sea. The UK should seize this opportunity to show leadership in a key region for global biodiversity and climate action.