Christine Cunniffe chokes up a little when I ask her about the children who have left her school since VAT was levied on their fees. “It’s been done quite quietly. I feel for their pain. You can only imagine what it must feel like for a 13 or 14-year-old, where they’re thriving and they’ve got their friendship group, to be basically starting again. If I were a parent, I would be hopping mad.”

Cunniffe is head of LVS Ascot, a non-selective, independent—no one in the sector uses the word “private”—school in Berkshire. “Not everyone is going to Oxbridge,” one of its teachers told the Good Schools Guide, which is their way of saying that the school is not especially driven by exams. Indeed, no one did go to Oxford or Cambridge last year, though a number got places at Russell Group universities.

Around a quarter of LVS pupils have special educational needs, or SEN—across the country, the figure is 20 per cent—but none seriously enough to have been given an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP), which entitles children to extra support.

The most competitive private schools, which have gruelling entrance exams and a strong academic reputation to maintain, do not cater for these children. But less well-known ones do, and it is parents at these schools who feel the VAT imposition especially keenly. Sometimes their children went private after struggling in the state sector.

“The number of children with special educational needs and disabilities within independent education has increased hugely over the past 10 years—by over 78 per cent in ISC-affiliated schools,” says Sarah Cunnane of the Independent Schools Council, which represents the interests of 1,400 private schools across the UK. “We know that many parents have chosen an independent school for their child because of their struggle to find the right support or to navigate the complicated EHCP system. Over 100,000 children with SEND but without an EHCP attend an ISC school and have no exemption for VAT on their school fees.”

Private schools have always argued that they do the government a favour by saving the state the cost of educating nearly 600,000 children. Their parents have already paid twice over for their education through general taxes and school fees. For them, VAT of 20 per cent feels like the final straw.

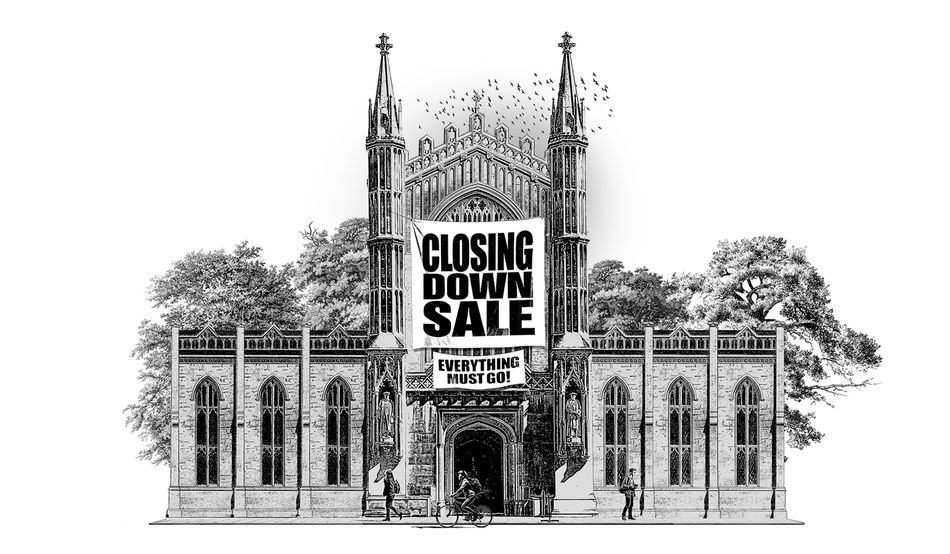

The past year has not been easy for private schools, and they have not been afraid to say so.

A group of parents and teachers forced a judicial review, arguing that SEN children without an EHCP receive inadequate support in state schools and should not be taxed on the education they buy as a result. It failed, but the judgement makes sobering reading for any parent. “The fundamental difficulty with the claimants’ case,” said the judges, “is that the clear evidence they rely on shows not only how bad it might be for them if they had to transfer to the state sector, but also how bad it currently is for many of the 1.1m children with SEN who are already being educated in that sector.”

Cunniffe is aghast at the levy, which is intended to raise £1.7bn a year—money to hire 6,500 more state school teachers. She says it has already led to a 10 per cent fall in her roll. “All it’s done is displace children and cause anxiety. There’s got to be a better way of raising money for the poorest children.”

But is there? Ninety-four per cent of kids go to state schools, and the staff shortages are acute. Almost a third of schools in the poorest areas can’t even offer computer science A-level because they lack a qualified teacher, according to teacher training programme Teach First. This is despite the government’s ambition to become a “world leader” in AI. Cunniffe insists the problem is the failure to attract people to join the profession, rather than a lack of investment. “Teaching is not a respected profession. The government has to stop attacking other people and deflecting from other issues. We just want to do the best by all children.”

The past year has not been easy for private schools, and they have not been afraid to say so. Overall, their pupil numbers fell by 11,000 or 1.9 per cent in the year to January 2025, but it is hard to tease out how much of that is due to the VAT and how much is down to the falling birthrate. The number of state pupils also fell, by 0.6 per cent. Inflation, higher pension contributions and the changes to employers’ National Insurance contributions were other burdens. But for private schools, the shock of being targeted was profound.

Half of schools in the sector have long enjoyed tax breaks through their charity status. Fees have outstripped inflation for decades, but that was down to the schools and their race to outdo each other with ever better accommodation and sports facilities. “This is the first time in nearly 150 years that a political policy threatening to negatively impact the private school sector has made its way through cabinet and the ensuing right-leaning media storm,” says Jess Staufenberg of the Private Education Policy Forum.

The fact that only one of Keir Starmer’s original cabinet went to a private school probably had a great deal to do with the policy being one of the few from the Corbyn era to survive intact. To grasp how remarkable that statistic is, you need to compare it with every other cabinet since the Second World War. All of Anthony Eden’s ministers had a private education. Until now, the proportion of ministers who were privately educated has never dropped below 30 per cent.

The policy was presented as a way of raising money for state schools rather than cutting the numbers of students going private—indeed, the two aims would work against each other, if state schools had to take on kids previously educated privately—but the PM is said to be adamant about the importance of decent state provision and not buying privilege. As a teenager, he reportedly kicked back against his headmaster’s determination to change his grammar into a private school. He particularly dislikes the “posh games-playing aspect of politics, the people who sneered at him for going to Leeds [University],” says one insider. Starmer made great efforts to ensure that both his children stayed at state schools when he moved into Number 10, despite the difficulty in ensuring their privacy.

But even this government shrinks away from openly questioning the decision of parents to send their kids private. The urge to give your child the best education you can afford runs deep, and is just as common among parents from minority backgrounds. Watch the BBC’s drama Boarders, which follows five black sixth formers on scholarships to the fictional St Gilbert’s, and you understand how private education functions in British society: it is a coveted opportunity, not to be turned down for the sake of principle.

St Gilbert’s is a second-league private school which is anxious to keep its charitable status by proving how inclusive it can be. Boarders expertly skewers its snobbery and performative diversity. The sixth formers take drugs and have sex in front of their roommates. Yet by the end of series two, things are mostly working out well for the scholarship kids. One of them has been offered the chance to study in the United States; another aces the inter-school maths challenge; a third is coming to terms with his sexuality. St Gilbert’s is insufferable. But it does the job it is meant to do. These sixth formers have opportunities they would not have had in a south London comprehensive. By the end, none of them seems to want to go back.

“To not understand that there are legitimate, heartfelt reasons why parents who can afford it choose the private sector is clearly ridiculous,” says Staufenberg. “But one of the problems we have as a country is [that] we don’t have enough media coverage that covers both sides in a balanced way.”

Francis Green, professor in work and education economics at University College London, agrees: “It’s very difficult to have a rational discussion in public.” Almost every time a private school closes, the right-wing press blames VAT: the Telegraph counts 44 so far. “But schools open and close all the time. That’s the nature of small businesses.” He says they have more financial leeway than they claim: “There is plenty of room for cost savings across the private sector. They have enormous resource advantages over state schools, and there would be plenty of scope for reducing those.”

Cunniffe disagrees. “You’ve got to maintain your buildings, we haven’t got grandiose facilities.” (Not, perhaps, by the standards of some of her competitors, but the 25m swimming pool and 26-acre wooded campus are “among the best in the UK”, claims LVS’s website.) “The price of teachers is huge… a maths or physics teacher can basically demand whatever they want. [Staff costs] could be up to 70 to 75 per cent of school costs and we can’t even claim the VAT back on that.”

What Green does not dispute is that scholarships can often give less well-off pupils a strong advantage. He did some work on the impact that bursaries at Christ’s Hospital school had on their recipients, compared with pupils from the same boroughs who were state educated. They had a “significant impact, probably more than any normal private school”. Schools such as Winchester College, which charges £60,000 a year for boarders, make much of these bursaries: beautifully edited videos show the grateful pupils explaining how their lives have been transformed. Yet they are a very small minority, and always have been. Around 1 per cent of private school places are free, a figure that has not budged for decades.

Bursaries are one of the ways that schools with charitable status justify their tax breaks. Another is the partnerships they set up with state schools—but the evidence that these make any difference is almost non-existent. Staufenberg’s research team asked almost 300 of the state schools in these partnerships about their impact. Very few private schools were formally evaluating them, “so nobody seems to be checking whether the partnerships do anything at all”. The majority of these schemes were “superficial—joint carol singing, attending a theatre performance at the private school. There was much, much less aimed at disadvantaged pupils”.

The Education Policy Institute, a charity, did a closer study of two partnerships. It found the private school pupils were glad to have the chance to become “more open minded” and “mixed with people we wouldn’t mix with otherwise”. State pupils saw it quite differently. “The interactions felt quite condescending,” said one. Another commented: “I feel like they think they’re better than us.”

“We did some research on these partnerships at UCL,” says Green. “The state school heads tended to be ambivalent. In one case the local private school was using it to poach their kids—they had joint sports events, and the local private school was showing off their facilities to the state school parents. The state school head said she’d stopped it.”

“Admirable people within the private school sector will openly admit that too much of it is lip service,” says Staufenberg. The Charity Commission tried to tighten its guidance on how “public benefit” was defined in England, but the ISC successfully challenged that in a judicial review in 2013. This means it is broadly up to a charity’s trustees to decide whether what they are doing amounts to a public benefit. As Staufenberg puts it, schools mark their own homework. Is that really enough? “Many schools now produce impact reports showcasing how their partnership work is benefitting their local community,” says Cunnane. You wonder who reads them.

For the most prestigious private schools, there is another way to ensure survival. Until 2010, satellite campuses were rare, but now 50 British schools have at least one outpost abroad. Harrow, Rugby, Benenden, Repton and Uppingham are among those to have opened campuses across Asia and the Middle East. Schools with charitable status pay no corporation tax on these ventures. Last year Charterhouse opened a school in Lagos: “Our school is a reflection of our confidence in the future of Nigeria and we want your children and your family to be part of that dream.” The Harrow school jargon (“beaks”, “ducker”, “jibs”) is the same in Shanghai as it is in England, the pupils still wear a straw hat that must never be called a boater, and the senior staff tend to be British. Parents want that and will pay for it.

How could you not give your child every advantage you can afford?

In this way, the original school preserves its exclusivity and mystique but exports some of its allure to places where, despite the dubious legacy of colonialism, a certain myth of Britishness abides. “British teachers, they shaped my character and my values,” one wealthy Nigerian parent who sent his child to an English boarding school told the University of Suffolk researcher Pere Ayling. “I have also believed a Briton is an independent-minded person. He has family values. He detests criminality. He is a cultured person.” Another insists: “The British teachers are very well qualified, and their mentality is different from… Nigerian teachers.” Like so many things about the cult of the British private school, it makes you wince.

There is a moral case for sending your kids to state school. To remove children from the company of the vast majority of their peers and buy them a better education is to write off any aspiration to social equality. It siphons off the wealthiest families and leaves them with no interest in improving state education or empathy with the struggles of the rest. Making this case is rather embarrassing, since the vast majority of Britons have no choice in the matter. But Staufenberg puts the downside in stark terms. “You could argue that in certain private schools, you are risking the personality of your son and daughter. It sounds dramatic, but they may be entering a world in which almost everybody is well off, and nobody speaks, sounds or thinks very differently to them… It can breed a kind of competitiveness, ignorance and intolerance that teachers don’t always see. I wonder if parents consider carefully enough what the risk may be to their own child.” She recalls seeing a boy from a top private school waving a £20 note at a homeless man, taunting: “Wouldn’t you like that?”

And yet. How could you not give your child every advantage you can afford? Somewhere on the playing fields of England are a handsome boy and a joyful girl who know what to say in their university interviews and already have the confident charm that will mark them out for the rest of their lives. Manners makyth man, as Winchester College’s motto boasts. Can you really deprive them of that, just for the sake of understanding what the rest of Britain looks like?

As parents are priced out of a private education, more could find themselves making a virtue out of a necessity. Already a few of the poorer members of the HENRY subreddit (High Earners Not Rich Yet, or people earning over £150,000) are talking up state schools to their sceptical peers who watched Netflix’s Adolescence and shudder at the failings of the school it depicts. Cunniffe complains that the VAT levy has made private schools “even more exclusive”—and she is right. Perhaps more parents will now ask themselves how much inequality a society can bear. Do they want to add to the burden?