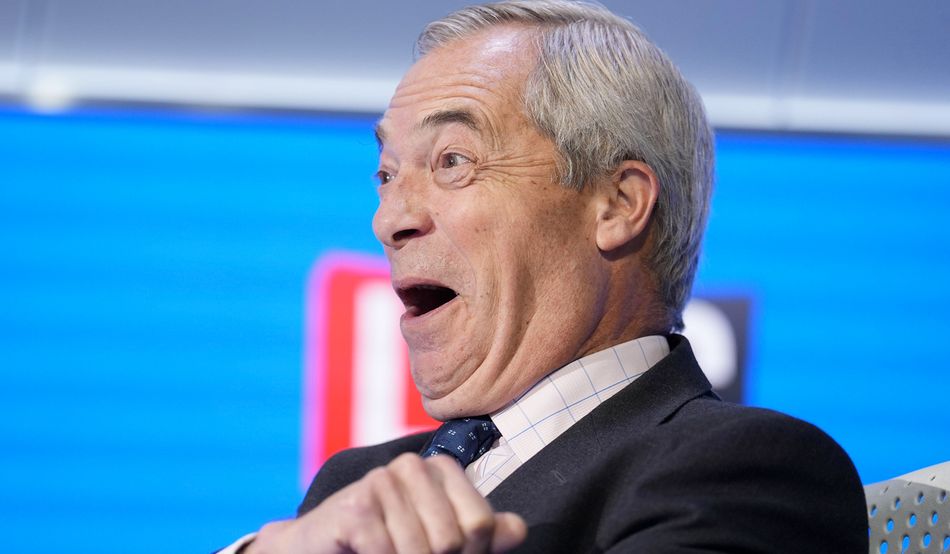

Since the summer, Keir Starmer has taken to lashing out at Nigel Farage. Last week he branded Farage’s immigration policy as “racist” and “immoral”; in his Labour party conference speech yesterday, the Reform leader had become “the enemy of national renewal”.

But Starmer’s real enemy isn’t Farage, it’s the state of the country. It’s the economic stagnation, the tax rises, the ballooning national debt, the botched Brexit, the astronomic fuel bills, the overwhelmed NHS, the escalating trade wars, the small boats full of immigrants crossing the Channel and a sense of general policy failure bedevilling the country. Virtually none of which has been reversed since Labour took office last year.

Starmer needs a story to tell about the UK getting better, and he desperately needs to energise his government and his party to carry through a reform programme that delivers this. Speeches and media messaging are two of the main tools that a leader has to motivate his followers, and they certainly need it if the government is going to gain control of today’s deep national crisis.

So why is Starmer instead focusing so much on Farage? In particular, why is he doing so now, four long years before a general election is due? For months he has hardly stopped attacking him. His conference speech dialled this up to a new level, making bogeyman Farage the personification of a choice between “decency and division”.

The obvious answer is that he is demonising Farage as an act of desperation at the state of the polls. They have reflected a sharp rise in support this year for both Reform and for Farage personally. Reform is well ahead of Labour in all recent polling, and the latest Ipsos survey on “best prime minister” has Farage tied with Starmer.

The strategy is obvious. Paint Farage as a dangerous extremist and it is just possible that he could lose the next election on that basis alone, much as successive right-wing anti-immigrant Le Pens have lost presidential elections in France to centrists, including to Macron in both 2017 and in 2022, despite the grim state of France.

For Starmer, the next election that matters isn’t the general election due by 2029. It is the local and regional elections next May, which could unleash another wave of crisis for the prime minister if Reform outpolls Labour and if the SNP wins the Scottish parliament elections. Angela Rayner has been (at least temporarily) removed from the scene, and Andy Burnham may have shown his colours too soon. But they and others may be besieging Number 10 in just another seven months’ time.

There is also a real fear, shared by Labour and Tory strategists alike, that Farage and Reform could surge further, and imminently. If polling for the Tories does not improve rapidly, there could soon be an avalanche of defections of Tory MPs to Reform, including shadow cabinet figures. The Tory party could be on the verge of collapse. Remaining Tory support might then shift wholesale to Farage, putting him in a commanding position.

Of course, attacking Farage personally is a dangerous game. It gives him yet more publicity, and an even bigger campaigning chip on his shoulder. He has seized on Starmer’s “racist” remark to claim that his own security is now under threat.

There is another reason that Starmer is going for Farage, however. Unlike Blair and Thatcher, he doesn’t exude passion, and day by day he barely breaks through to the public or even to most of his party. The ostensible theme of his conference speech—“a Britain built for all”—isn’t going to fire up the government, let alone Labour activists who need a cause and a campaign.

Starmer’s revulsion at Farage has been the one thing to evoke genuine passion from him, ever since the Reform leader’s controversial interventions in the wake of the Southport murders shortly after the general election last July. His advisers are clearly of the view that passion is better than no passion, and it is better for him to have an enemy than no enemies.

But the national crisis isn’t going away. And that remains the real enemy.