Last year was Year One of the west’s political revolution—our 1989. Just as statues of Lenin were toppled from plinths when the Iron Curtain collapsed, today the pillars of our own system are crumbling everywhere: from a failing European Union and free trade lobby to old media and calcified political parties. Despite the events of 1989 and 2016 being decades in the making, they managed to catch experts unawares. After the Berlin Wall came down, western cosmopolitans and technocrats raced to claim victory. Yet beneath the euphoria of the New World Order, our own contradictions were festering—stagnant wages, gaping inequality and a feeling that most people had no real control over their lives. Another quarter of a century passed before the other shoe finally dropped. Only in 2016 did citizens in the west finally become agents of revolutionary change—for better or for worse.

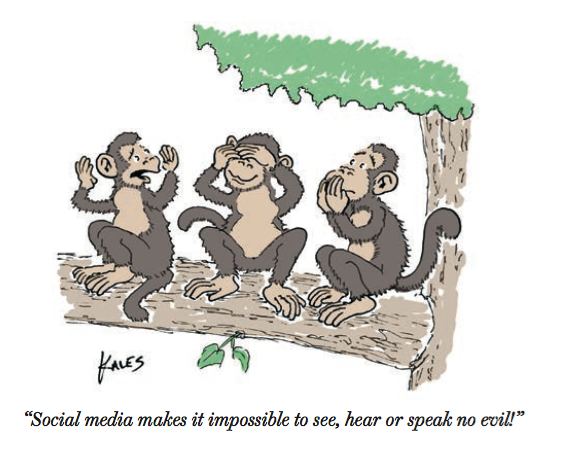

The rules of politics have been upended, in no small part, by new communication technologies. Liberals who resent the Brexit vote and the election of President Donald Trump point the finger at social media, seeing in it an echo chamber that entrenched false ideas (Cass Sunstein’s #republic, which takes exactly this line is reviewed in this issue). I understand their growing alarm about how costly and sophisticated data analytics enable some plutocrats to buy influence from the shadows. But I am resolute that technology’s power to connect citizens, transform access to information and move them to action will ultimately prove to be an instrument of enlightenment and positive change. The self-styled “progressive” establishment, which talks the talk on empowering citizens, has only itself to blame for its failure to keep pace with the disruptive implications of the smartphone age.

Much as I wish this moment had arrived differently, I saw it coming long before the last 18 months, during which I’ve spent time behind the scenes with winning insurgent campaigns from Brexit to the US and beyond. After dedicating the first years of this century to work around Middle East peace, democracy and Europe’s doomed Constitutional Convention, I came to see that our whole way of doing politics was broken. A growing band of us started harnessing technology to reconnect people with power. I had the privilege to work on campaigns engaging tens of millions of people around the world. I helped to build the global civic activism online network Avaaz, co-founded the British campaigning community 38 Degrees and led the global growth of Change.org.

Some have sneered at such “clicktivism.” But this caricature misses the fact that the new networks have already done more to co-ordinate campaigns and activity offline than many political parties. Besides, if there were still a lingering doubt about the political importance of such activism, the tumult of last year should have killed it off.

Increasingly, the new networks of politics are moving money as well as hearts and minds. My main work today is as co-founder of Crowdpac—the open platform that helps citizens to crowdfund campaigns that rival the power of big donors and their Political Action Committees. I am from the left, but another Crowdpac co-founder is Steve Hilton, who created David Cameron’s Conservatism, then shrewdly foresaw its downfall, and now dedicates himself to the next revolution. We disagree on much, but share the belief that our democracies must be overhauled. Tribalists of left or right are wrong if they think they have a monopoly on the revolution in the way politics is done.

In the last year or two, for all their differences, Trump, Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn and the Brexiteers each achieved the apparently impossible. All of them were carried to unexpected heights by new movements, which harnessed technology to unleash pent-up reservoirs of energy—even if their leaders did not fully understand them. These insurgents are not a flash in the pan. Trump and Brexit are shredding the fabric of the western order. All eyes now turn to the French presidential election, where the modernised Front National is battling it out with ex-banker and civil servant Emmanuel Macron’s upstart and digitally-charged liberal movement, En Marche! It has never been more urgent to grasp how and why the “outsiders” are winning.

Throughout history, changes in the way that citizens communicate have unleashed disruptive people power. Gutenberg’s printing press opened the door to the Reformation, destabilised the Holy Roman Empire and enabled the spread of subversive ideas during the English Civil War. By the second half of the 18th century, social power was manifested in debating societies, coffeehouses, pamphlets and newspapers—the nascent public sphere that helped give rise to the French and American Revolutions.

But communications technologies can also be an instrument of top-down manipulation. For much of the 20th century, centralised broadcast media drove a mass-produced politics: think of the sinister might of Joseph Goebbels’s “People’s Receiver,” or—at the other end of the ideological spectrum—the “fireside chats” that Franklin D Roosevelt used to marshal support for New Deal populism. Border-straddling media, such as the West Berlin television that East Germans could watch, later helped to melt the geopolitical ice of the Cold War, by opening eyes to different ways of life. Throughout the 1990s, globalisation, the internet and mobile phones created even more complex networks—but politics lagged behind. The party cartels focused on centrally-scripted “lines to take” in the national media. Third Way politicians like Bill Clinton and Tony Blair put a warmer gloss on the Margaret Thatcher-Ronald Reagan settlement, but dismal voter turnout, which fell below 50 per cent in Clinton’s re-election year of 1996 and collapsed in the decade before the 2001 UK election, revealed that all was not well: politics was becoming an empty stadium.

On the outside, networked campaigns started growing on all sides. Movements popped up to challenge global summits. Blair was forced to the brink in 2000 by a swarm of angry lorry drivers, who used early mobile phones and text messaging to co-ordinate a refinery blockade over fuel taxes. After conventional campaigns failed to stop the invasion of Iraq, digital activists started getting more political. The so-called “netroots” movement powered Howard Dean’s brief but energetic US presidential campaign in 2004, helped win back Congress for the Democrats in 2006, and played a pivotal role in the campaign that elected Barack Obama. Sadly, the Obama “movement” centred too much on just one man—and a cautious man at that. In the face of the global financial meltdown, Obama chose continuity over change. The bill for the banks’ failures was passed on to ordinary taxpayers. The wave of hope crashed away, and the populist high ground was ceded to the Tea Party—a network of conservative grassroots activists and big money donors who won many elections and refused all compromise.

For good or ill?

In The Seventh Sense, the political thinker and Henry Kissinger’s business partner, Josh Cooper Ramo, describes the political effects of network power. He highlights how the new political order is based on frictionless many-to-many communication, from email lists to social networks and instant-messenger groups. This enables people to find allies in an instant. In the 18th century, it took campaigners against the slave trade five years to raise 390,000 signatures from all over Britain. Today a petition can gain hundreds of thousands of supporters in a day on Change.org, Avaaz or 38 Degrees. Within a week, those people can be crowdfunding an advertising campaign. Within a month they can be organising simultaneous mass demonstrations.

I know this better than most. Every day I watch dozens of campaigns created by people on Crowdpac: from doctor Kathryn Allen crowdfunding half a million dollars to challenge the conservative US Congressman Jason Chaffetz, to Momentum, the Green Party and Owen Jones’s Stop Trump Coalition in the UK. Our platform is open to all, including the newly independent libertarian MP Douglas Carswell—who has long been a fan of Crowdpac—and his nemesis the populist multi-millionaire Arron Banks, who will soon launch his Patriotic Alliance. It is not about special favours from us: everyone plays by the same rules. (Crowdpac is a for-profit social venture that, in the US for example, is funded through voluntary contributions from our citizen-users, typically 5-10 per cent on top of each small donation.)

"Communications technologies can become instruments of manipulation as well as tools of empowerment"Early adopters have played a special role in accelerating the campaigning revolution. They have Ramo’s “seventh sense”; they can see the potential in the network. Former Google executive Wael Ghonim created the Facebook page that played a critical role in the organisation of the Egyptian revolution in 2011. While the Tahrir Square movement failed to channel its power into electoral victories, it was a genuinely bottom-up affair, made possible only by combining social networks with street organising.

A lot of the necessary technology is free, and it can work for anyone. But revolutionary times are fertile ground for false prophets, propagandists and tyrants. Communications technologies can become, as we have seen, instruments of manipulation as well as tools of empowerment. Who will win? Will a data-rich oligarchy solidify its control and protect its interests through “elite populist” campaigning? Or can democratic movements build a new order that better serves the people?

For many liberals the US presidential election of 2016 was a lesson in how social networks, far from enriching democracy, could destroy it. In February 2016, the plutocrat Trump addressed a rally in the US state of Georgia: “I want everybody talking about a MOVEMENT,” he said. His aide Dan Scavino repeated the meme on Twitter: “THIS IS A MOVEMENT!”, a message the man himself amplified with his own tweets again and again: “This is a movement like our GREAT COUNTRY has never seen before!"

True: it was all built out of thin air by an artist of a traditional, top-down “air war.” Trump got billions of dollars worth of television time for free, driving media cycles with every controversial tweet or seeming misstep. His campaign was car crash television but it hammered home his messages: “Build A Wall”; “Drain The Swamp”; “Crooked Hillary”; “Make America Great Again.” Brilliantly, if shambolically, Trump nailed his narrative. The rallies and the social media campaign grew up underneath him—part-spontaneously, and in part because they were cultivated by guiding intellects and big cheque books. Whipped up by controversialists like Milo Yiannopoulos, they started self-organising chaotically through Facebook, Reddit, Gab.ai and other networks—and their spontaneous energy proved as powerful as it did because of other operators who were standing by, ready to harness the frenzy.

Trump’s towering analytics

Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, took early control of the Facebook campaign. “I called some of my friends from Silicon Valley, some of the best digital marketers in the world, and asked how you scale this stuff,” he told Forbes. “They gave me their subcontractors.” Kushner and the campaign’s Digital Director Brad Parscale started matching voters to their Facebook profiles, and used that platform’s “Lookalike Audiences” function, which identifies people whose profiles are similar to those of existing supporters. Kushner is also friends with Peter Thiel, a libertarian billionaire, who was one of Facebook’s original investors, and the man who wrote that: “The fate of our world may depend on the effort of a single person who builds or propagates the machinery of freedom that makes the world safe for capitalism.” While Trump—that “single person?”—played the old media with devil-may-care chutzpah, newer outfits stoked his insurgency.

Breitbart News, the website led by Trump’s old friend Steve Bannon, was among his biggest cheerleaders. A former Goldman Sachs banker, Bannon went to Hollywood to become the conservative equivalent of documentary controversialist Michael Moore. And as his mind turned to electioneering, he knew exactly how he wanted to set about it: “I wouldn’t have come aboard, even for Trump,” he said, “if I hadn’t known they were building this massive Facebook and data engine.” After all, “Facebook is what propelled Breitbart to a massive audience. We know its power.” Bannon was until recently on the board of the big-data firm Cambridge Analytica, whose creation he apparently brokered with the family of Robert Mercer—the reclusive conservative hedge fund billionaire, recently profiled in the New Yorker as the “tycoon behind the Trump presidency”—who had also funded some of Bannon’s other projects.

The genesis of Cambridge Analytica is murky. It seems to have been in the works at least five years ago, around the time “Big Data” was seen to win Obama’s re-election. Bannon and the Mercers teamed up with the UK-based organisation called Strategic Communication Laboratories (SCL), which has claimed to work with Nato, the US and governments around the world on “psychological warfare” and “influence operations,” as well as on over a hundred election campaigns.

Bannon introduced Analytica to Trump early, at a time when it was still playing a key role in Ted Cruz’s campaign. After the Indiana primary, when Cruz’s hopes vanished, Analytica and the Mercers embraced Trump; and in August, Trump ousted his campaign manager Paul Manafort in favour of Bannon and another Mercer ally, Kellyanne Conway.

Analytica bought masses of US commercial and political data and used “psychographic” questionnaires, Facebook likes and other data to build a sophisticated understanding of voters’ motivations and triggers. Sceptics have challenged Cambridge Analytica’s claims; the company has even sought to downplay its role in the campaign. But they definitely did psychographics for Trump; and the track record of those involved suggests to me that they may indeed have built unprecedented capabilities. Analytica helped give Trump’s campaign—which was lagging in the polls, and would continue to lag in the national popular vote—exactly what it needed in order to have a chance. It pinpointed 13.5m potentially persuadable voters in 16 battleground states.

At the height of the campaign, Parscale’s online operation was spending $70m a month, while raising similarly large amounts from small donations. A senior campaign official told Bloomberg’s Sasha Issenberg: “We have three major voter suppression operations under way.” These black ops worked on multiple levels. Young women were targeted with Michelle Obama’s 2007 comment about Hillary that “If you can’t run your own house, you can’t run the White House”; and black voters with Hillary’s 1996 comment about “super-predators.” Similar messages were communicated by Trump himself, on talk radio and through secret “dark posts” promoted on Facebook. They spread like wildfire.

For all its resources, the leaden Clinton machine was locked into an older mode of operation. The campaign boasted of its own data models, but in the final analysis these turned out to be wrong—partly because the campaign’s leadership ignored feedback from the electorate. On election day, the Clinton campaign’s get-out-the-vote effort turned out a considerable number of voters who had actually switched to Trump.

Meanwhile Bannon’s team had invested heavily in the fateful Rust Belt battlegrounds: Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Wisconsin. Trump’s final ad, “Argument for America,” presented Clinton as an establishment stooge, and promised to “take back this country for you.” The rest was history. To those of us who had lived through Brexit, the outcome was eerily familiar.

It could happen here—and did

When I sat down before the launch of the EU “Remain” campaign with its director Will Straw, he told me he was building an Obama-like field machine, bringing together volunteers with the data and Facebook expertise of David Cameron’s digital campaigners. But No 10 was dictating his strategy, and he seemed overly focused on the traditional swing voters that so obsessed Blair—suburban, middle-class, small-c conservative, moved by fear of economic disruption. I warned Straw to pay more attention to the left-behind voters who Dominic Cummings, the campaign director of Vote Leave, was targeting.

An anti-establishment iconoclast who had prepared for this moment for decades, Cummings has chronicled his strategy in a series of lengthy blogs. Like me, a student of the sociological uses of science and the “political technology” used by post-Soviet spooks, he has referenced the tactics of Vladislav Surkov, the “grey cardinal” of Putin’s Kremlin. Cummings saw clearly how new technology could tap the dissatisfaction of the hour. He realised how powerful the “Take Back Control” message could be, wrapping anxieties about identity, the economy and immigration together under a banner of individual re-empowerment. He grasped that working-class Labour voters in small-town England were the swing vote now, and targeted them relentlessly. He was ruthlessly empirical; and the line that “we send £350m a week to Brussels, let’s fund our NHS instead” was his most controversial and effective. Every time an outraged Remainer argued with the misleading headline number, they only drew attention to Cummings’s message.

Vote Leave was lucky that none of the attempts to clip Cummings’s wings succeeded. It had plenty of more traditional operators who grasped neither the disgruntled mood of the hour, nor the disruptive potential of the technology. The campaign’s Chief Executive Matthew Elliott told me he thought that turnout would not be much above 50 per cent, less than two years after well over 80 per cent voted in Scotland’s referendum. I was astonished. I was always convinced that in an election like this—where every vote counted, and a year after Ed Miliband had failed to offer the country the change that it craved—people across the land would want to stand up and be counted.

In the end Cummings carried the day with a surgically precise campaign. He ran ingeniously targeted ads for different audiences on Facebook, and mobilised tens of thousands of canvassers, who would provide the raw data that was continually used to check and refine his model. They spent 95 per cent of their advertising budget online, buying one billion targeted digital adverts to saturate the social media feeds of their targets. In the last few days they gave £625,000 to Darren Grimes, a 23-year-old Lib Dem-turned-Tory from County Durham. Grimes immediately hired a Canadian political data consultancy called AggregateIQ, whose director was a former SCL representative. It promoted a nominally independent BeLeave youth campaign through social media and text messages.

"Neither Trump nor Brexit could have won if they weren't riding a groundswell rooted in real public grievances"Meanwhile the parallel “Leave.EU” campaign, run by Banks, cheerfully embraced the post-fact era in much the same way as Trump. He and his co-conspirator Andy Wigmore consulted data modellers, including Cambridge Analytica, to identify where Nigel Farage should campaign. They built a supporter base through social media and a 100-staff-strong call centre, hammering politically incorrect messages about immigration, terrorism and identity.

The two “Leave” campaigns seemed to hate each other; and for the sages of Westminster this spelt disaster. The game, as they saw it, was about dictating a clear top-down line and getting it across on the 6pm and 10pm news. But in practice, in this new world of fractured perspectives—where social media turns every citizen into an editor—the division between the two was brilliantly effective. The warring campaigns won plenty of media, presented different but aligned messages to two different audiences, and combined to persuade a winning coalition of voters. The “Remain” campaign’s failures meanwhile closely mirrored those of Clinton.

Feel the Bern

Many people who share my political view see Trump and Brexit as demonic counter-revolutions, pure and simple. I disagree: neither campaign could have won if they were not riding an authentic groundswell rooted in real public grievances. But I am now intensely concerned about the potential impact of elite populism and big-data war machines on our democracies. So how can I maintain my optimism that the new campaigning methods will in the end allow us to build a more progressive and truly democratic politics?

The answer is simple—Bernie could have won. Within 24 hours of declaring his presidential run in April 2015, he had signed up 100,000 supporters and raised $1.5m in small donations. With the party behind her and a lock on the media, Clinton was not just the favourite but a shoo-in. Sanders, by contrast, had just 3 per cent name recognition. Nobody thought he was in the running. And yet by the time of the Democratic National Convention in 2016, he had 46 per cent of the pledged delegates. How did this happen? After Bernie won the New Hampshire primary and proclaimed the Political Revolution on national television, I decided I had to see what his team was building. I got to Vermont at the end of February last year. It was the weekend before Super Tuesday, the biggest day in the American presidential primaries. I was the first writer allowed inside Sanders’s ramshackle campaign headquarters. What I saw blew my mind.

The Bernie movement was powered by tens of thousands of volunteers. They had massive gaps to close. But that weekend, they’d made over 2.3m calls; in the next two days, they would send almost 800,000 personal text messages to get out the vote. Meanwhile, a thousands-strong volunteer helpdesk was calling up supporters to advise them on their own events and help them network with other Sanders believers.

I spent the next week on the road with the campaign, travelling from Colorado to Miami. Claire Sandberg, who had cut her teeth working on anti-fracking campaigns, introduced Sanders to a roaring stadium of 15,000 people in Michigan, then signed up thousands of them as volunteers. Sanders preached an extraordinary sermon about the gutting of Detroit and Flint, and issued a challenge: “Michigan can play a profound role in transforming America and helping us to go forward in the Political Revolution.” Nate Silver, the political forecaster, had predicted with 99 per cent certainty that Clinton would win that vote. But Bernie’s campaign put out millions of calls and text messages—and won.

"The old order, wrapped in a cloak of well-packaged facts, carpet-bombed the electorate with fear"Where did the energy come from and how was it channelled? Even before Sanders declared, Occupy Wall Street activists had started an independent “People for Bernie” campaign; at its peak their Facebook page was reaching over a third of Americans, and it continues to drive massive engagement today. Charles Lenchner told me, “In every single state, Bernie’s people were already there and ready before a single staffer showed up. There were already dozens or hundreds of local groups self-organised on the internet.” Initially the campaign struggled to tap these chaotic energies. But a new “distributed organising” team, built by netroots veterans Zack Exley and Becky Bond with Sandberg and an all-star team, thought Big Organising was more important than Big Data. They built innovative open-source tools and systems, empowering hundreds of thousands of people to self-organise for victory. Today this model is taking hold across America through movements like Brand New Congress, #AllOfUs, Indivisible and #KnockEveryDoor.

The Sanders movement didn’t wait to be asked. It was based on the work of volunteers—people like Corbin Trent. A powerfully-built man from a small Republican town in Tennessee, Trent took over the family manufacturing business when his grandfather died in 2000. Within six years it had gone under. Imported parts and products were cheaper: “All of our customers kept shutting down, everything was going offshore… I worked in a local factory in the 1990s for $9.50 an hour—two decades later it employs people for $7.25!” he told me. When Sanders voted against the Wall Street bailouts in 2008, Corbin paid attention. Immediately the campaign was launched, he sold his food trucks business—and with zero political experience, put everything he had into organising Tennessee.

“There were all these Bernie Facebook groups starting up. So I started going round and talking to people. We got some different tools together, Nationbuilder, we started buying voter files in June, organising phonebanks…” Voter files help you target likely supporters and guide canvassing operations. They’re crucial, but Bernie’s old-politics campaign manager Jeff Weaver refused to invest in them for months. Before he’d even spoken to the campaign, Corbin was doing it himself. He was finally hired on to the “distributed organising” team: 2,000 people came out to meet him at a meeting in conservative West Virginia, “ready to get to work.”

More people signed up to the campaign every day, giving an average of $27 each. By the third quarter of 2015 Sanders had more small donors even than Obama in 2008. Sanders won big endorsements from networked movements with millions of supporters. The power of the crowd was raising just as much money as the decades-old Clinton machine. By the end, 2.8m people had given a total of $218m.

Yet many Democratic voters doubted Sanders’s ability to beat Trump. Clinton looked like the safer option. They ignored her failings, and discounted the polls, which overwhelmingly showed Bernie as the stronger contender. In the end, Hillary’s machine was just strong enough to beat him in the primaries. When the time came, and denied the chance to vote for Sanders, Michigan and its fellow Rust Belt states played a pivotal role in the political revolution after all: they tipped the election for Trump.

The night before Trump’s inauguration, I looked down on the White House from a victory party hosted by Banks on the top floor of the Hay-Adams Hotel. Farage was joyful: “What we did with Brexit was the beginning of what will turn out to be a global revolution…” The following day I listened to Trump preach Bannon’s America First sermon: “What truly matters is not which party controls our government, but whether our government is controlled by the people.” But which people? I was reminded of the words of Carl Schmitt, the 1930s German lawyer, philosopher and Nazi apologist. According to Schmitt, the “sovereign dictator” is licensed by his people to define their identity through conflict. Like Bannon and Trump, Schmitt rejected the liberalism of universal rights and open borders, demanding instead an endless “friend-enemy” confrontation—both internally and abroad.

I spotted my Bernie-organising friend Sandberg standing up with five others on their chairs at the inauguration to announce the resistance to Trump by reciting the constitution: “We the People of the United States…” As she was dragged off, she called out, “We’re for an America for all of us.” Winnie Wong of People for Bernie, now a key organiser of the Women’s Marches, told me they were expecting 300,000 people in Washington DC, but when the first march took place over a million showed up. That day became the biggest peaceful nationwide demonstration in US history.

And it was only the beginning. The old order, wrapped in a cloak of well-packaged facts, carpet-bombed the electorate with messages of fear in 2016—and it lost. The establishment, on both sides of the Atlantic, did not see that the essence of political combat had changed. It had no idea what it was up against; it may never recover, and it certainly won’t until it gets wise. But that doesn’t mean that politics is bound to veer off to the extremes. The new digital movements don’t automatically belong either to elite populists or to hard-left socialists. They’re available to all. In France, Macron has shattered the landscape with his new liberal and centrist politics. He has a fight on his hands against Marine Le Pen; but when I met his team, I was struck by how much they were borrowing from the Sanders campaign.

The west’s high noon arrived in 2016, and the most important single lesson is not to go into denial about this. So tear up your old maps. Get out of your comfort zone. Find new allies—or suffer the consequences. Economic systems are failing; old political cartels are losing their legitimacy. Elite populists and democrats are duelling. The need for transformational movements has never been greater—and at last they are rising up.