A century has passed since the first universal suffrage election. We’ve considered the vote a basic right ever since, but some British residents are still very much more equal than others where politics is concerned. Children aren’t eligible, of course, nor are four million (mostly foreign) adults: but their interests still need representing. On top of that is another significant—if hard to count—chunk who are not registered.

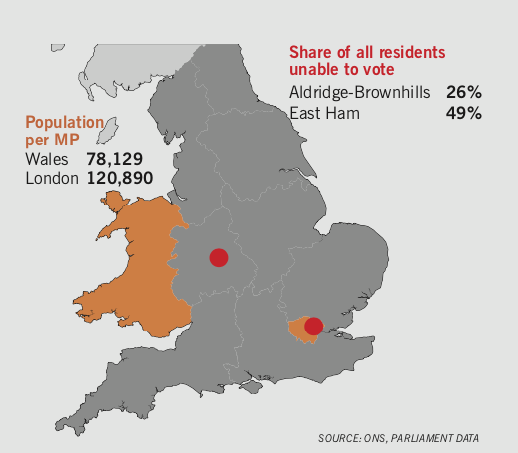

Significantly, none of these groups are randomly spread around. Young and diverse inner cities tend to have more non-voting residents than more sparsely populated regions. Differences between the nations of the UK in the actual electors required for a parliamentary seat compound the gulf.

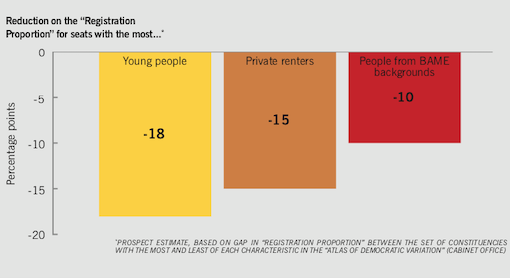

There is a sociological as well as a geographical slant. A prevalence of private renters, younger people and minority ethnic voters are all strongly associated with a lower “registration proportion” of residents. If these groups are feeling disenfranchised, here is one very good reason.

And do spare a thought for inner-city MPs. In some seats, such as London’s East Ham, one in every two residents cannot vote, while in others, such as leafy Alrdridge-Brownhills, it’s only one in four. Conscientious MPs will still do the casework for all residents. And that is often heavier for people who are—you guessed it—young, renting short-term or minorities. If British residents aren’t equal, then nor are their representatives.

One person =/= one vote

As well as 14m children, there are perhaps four million (non-Commonwealth) foreign nationals, 100,000 or so prisoners, several hundred Lords and a handful of electoral fraudsters. Oh, and one VIP in Buckingham Palace. On top of those who aren’t meant to vote is another chunk, who are potentially eligible but don’t “correspond” to an entry on the electoral register. In fact, the total number of “missing” voters will be higher than the 1.6m shown, because many Brits living abroad are on the register, and some (like students) are legitimately on there more than once, even though they can cast only one parliamentary vote.

The messy map of those without votes

The inner cities, particularly London, have more ineligible foreign nationals, and—compared to older suburbs and villages—more children too. On top of that, the system is biased to give Wales and to some extent Scotland extra seats. Even if the (endlessly postponed) 2018 Boundary review were to come into force, it would still only partially correct the regional mismatch.

Drilling down into individual seats reveals huge variation: sometimes half of all residents can’t vote; sometimes it’s only a quarter.

Some adults are less equal than others

Comparing the total electorate with the number of adult residents across seats with different demographics reveals a clear sociological slant. Having more minorities, more young people and more private renters are all associated with having a lower “registration proportion.” There is good reason to expect that groups who move home more often or face language barriers may be more likely to drop off the register.