It was the summer of 1997—a few months after a notable marathon libel case in which our crime correspondent, Duncan Campbell, had successfully defended his exposé of suspected corruption at Stoke Newington police station.

Around four in the morning, I was jolted awake by a burly policeman in the bedroom. We were living in Highbury, north London, and I soon worked out that the house was swarming with police officers, along with their dogs.

It turned out that a burglar had smashed through our front door in the middle of the night. The police eventually left and, as the last one disappeared up the path, he said to me: “You’re the editor of the Guardian, aren’t you? You might like to know we’re all based at Stoke Newington nick.”

My heart may have missed a beat. Duncan had, after all, just vanquished five of his colleagues in court. But I was wrong: as the copper tugged his dog into the van and drove off, he said: “Tell your Mr Campbell to keep digging.”

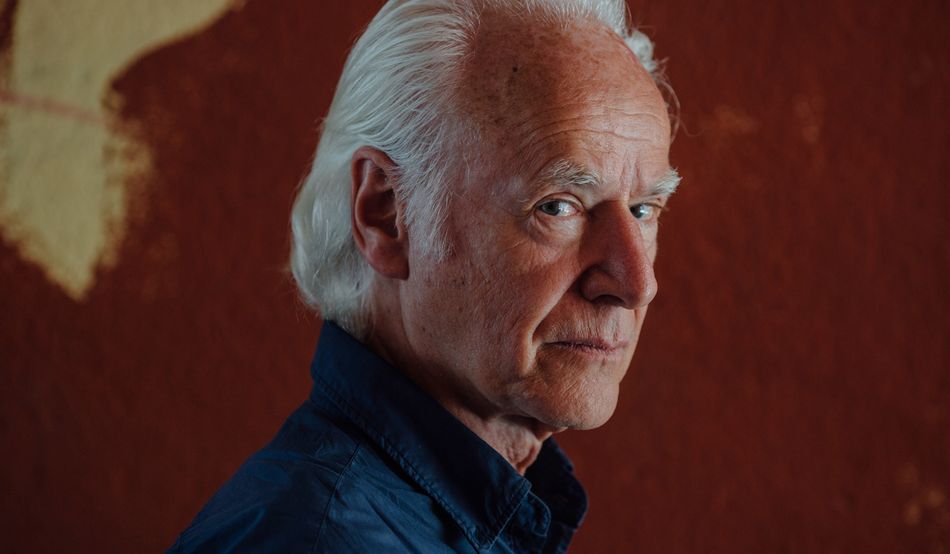

That was the thing some people struggled to understand about the way Duncan‚—who died recently—worked. You could expose bent cops and be in favour of the police. You could be dealing with the Met Commissioner as chair of the Crime Reporters’ Association in the morning and have a drink with a bank robber in the evening.

Of course, with Duncan, it went further, as anyone who attended one of his publishing parties would know. There would be chief constables, great train robbers, judges, barristers, old lags and old hacks. The art was to work out which was which.

Everyone trusted Duncan—except Mr Justice French in the Stoke Newington trial. In the previous 33 months, the police union, the Police Federation, had fought and won no fewer than 95 libel cases in a row. They were called “garage actions” because coppers would use the guaranteed settlement money for home extensions.

If Mr Justice French had had his way, the score would have been 96-0. But Duncan went into the witness box to give evidence. The jury, like everyone else, trusted Duncan. It cost him a huge amount in sleepless nights and anxiety, but the stand he took did his colleagues in the British press a considerable favour. It was now much safer to write about police corruption; it was a game-changer.

Duncan died within a week of another reporter, Andrew Norfolk, whose reporting on child-grooming gangs for the Times was similarly widely lauded for its courage and integrity. At a time when trust in the media is underwater, it’s heartening to be able to celebrate the best among us.

Duncan wrote about the world of crime like no other reporter could even dream of. How he did it, no one could quite explain. Nick Reynolds, son of the great train robber Bruce, told me: “You know, most villains hate journalists. I mean, the whole point of it is to try and do something and get away with it and be discreet. But somehow, through his integrity, approach, sense of humour, diligence, and demeanour, he managed to get the Golden Pass to the underworld, and they all respected him. “

Freddie Foreman, who killed people for the Krays, loved him. Mad Frankie Fraser, who extracted the teeth of his victims with pliers, adored him. But so did lawyers and police officers who cared about the truth.

He was very proud of the website he created, Justice on Trial, which ran until 2017 and covered numerous miscarriages of justice. He took an interest in so many. The Miami Five, the Craigavon Two, the Shrewsbury 24, the Birmingham Six, the Cardiff Three. The Torso murders, George Davis, and Gary McKinnon. Kiranjit Ahluwalia, who had been sentenced to life for killing her abusive husband. They and many, many more had reason to thank Duncan for swimming against the tide and taking the time and trouble to investigate their cases.

But most of the time, when people think about journalists, they don’t think of the Campbells and Norfolks. They don’t think of the risks that reporters take in covering events in the Middle East, or Ukraine, or even, as a new Amnesty International report highlights, in Northern Ireland, where there have been 71 attacks or threats against journalists since 2019.

When journalists are not being attacked physically, they are under attack verbally. It is now routine White House policy to denigrate, mock, discredit and delegitimise the so-called legacy media. The objective seems plain: if Donald Trump can persuade you that the New York Times is fake news, you might not believe them the next time they investigate his affairs.

The White House press secretary is 27-year-old Karoline Leavitt, who believes that Donald Trump won in 2020 and who used her very first briefing to (falsely) claim that $50m a year of US taxpayers’ money was going to fund condoms in Gaza. It’s unclear whether she has any journalistic experience, although she did once apply for an internship at Fox News.

This week, she took it upon herself to lecture the BBC on editorial standards, tearing into a report about deaths in Gaza and claiming the BBC had been forced to retract its claims.

This was fantasy stuff, as the BBC’s Ros Atkins demonstrated in a devastating three-minute film the following day. But, as the old cliche goes, Truth often takes some time to get its boots on. GB News presenters, for example, chortled with glee at the “humiliation” of the BBC seemingly without lifting a finger to interrogate whether any of Leavitt’s claims were actually, you know, true.

Atkins works for BBC Verify, which GB News owner Paul Marshall incidentally wants closed down. Truth, lies—who cares?

So journalism is struggling today. Which is why it’s worth pausing to remember and celebrate the best rather than dwell on the worst.

We said farewell to Duncan on Tuesday. He himself was a veteran of reporting on the funerals of the villains he’d known, including gangland figures such as Charlie Richardson and Ronnie Kray, as well as the Great Train Robbers, Buster Edwards and Ronnie Biggs. Though with one, Peter Scott, a noted jewel thief who died bankrupt and penniless in 2013, it was Duncan himself who ended up organising his funeral at Islington cemetery.

He arranged it at 10.15 in the morning: “There was a discount for the early hour,” he recalled. The undertaker demanded the deceased’s occupation. “Cat burglar,” said Duncan, who also chose the music for the ceremony. The coffin disappeared to the old gospel song, Steal Away.

It helps to have a sense of humour if your life is spent covering crime. Not to mention today’s White House.