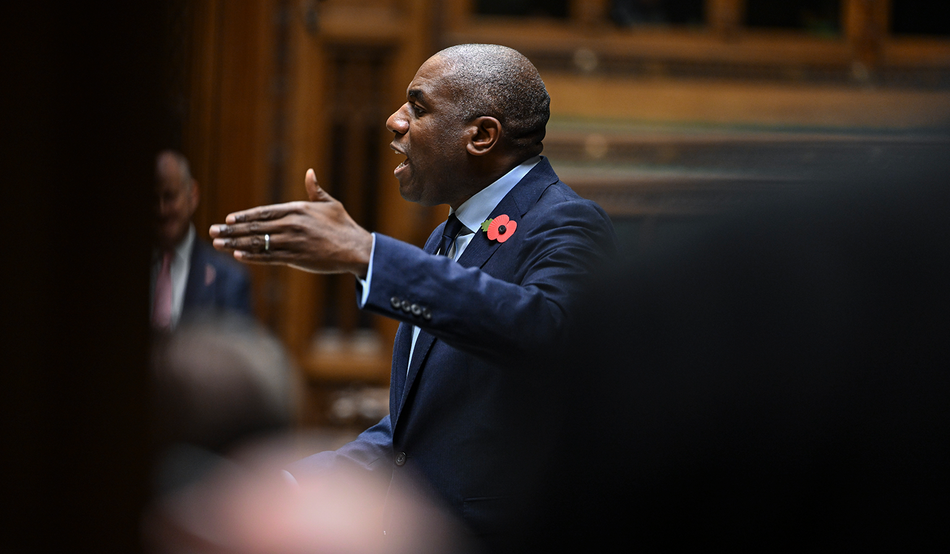

It hasn’t been the kind of month David Lammy would have imagined when he took the job. The new Lord Chancellor and justice secretary has quickly discovered why few politicians survive long in this role. A few days of scrutiny have exposed decades of dysfunction: chaotic release dates, a baffling sentencing system, archaic paperwork, and the inability of the Home Office, courts, prisons, probation and police to communicate. Now “Lammy’s Lags” will haunt him.

Much has been made of early prisoner releases, with little clarity about how early—years, months, weeks or days. Far less attention is given to people being released late or unlawfully detained; habeas corpus barely registers. And the question of what people are released to is almost never asked. “Released” is generous—“thrown out” is closer.

Many leave prison in a worse state than they entered it, physically, mentally and financially. Some develop debts or drug habits; others see their health collapse. On release, most receive little more than a tracksuit, a train ticket and a plastic bag of possessions. They rarely have the stabilising basics: a home, a job or supportive relationships.

It is unsurprising that in late 2024 it was found that 73 out of every hundred released prisoners were being recalled to prison. By June 2025, the recall population reached 13,538—the equivalent of nine prisons, costing around £3.5bn per year. Most are not recalled for new crimes but for failing to complying with their licence conditions, or in other words for failing to cope: for having nowhere to live, no income, and being managed by a probation service that is reduced to acting as a compliance agency. Preparation for release is minimal; support afterwards is thinner still.

These failures are symptoms of a deeper malaise. The one part of the system that works—oversight—is largely ignored. The chief inspectors of prisons and probation produce meticulous, damning reports that vanish into the ether. Accountability has lost all meaning in Whitehall.

Meanwhile, prison violence rises. Drugs are endemic, driven not by bored inmates but by organised crime. Education and employment programmes, long touted as the key to rehabilitation, remain inadequate; workshops stand empty.

We are told the problem is crumbling Victorian jails, overcrowding and underfunding. These matter, but even well-resourced prisons are in disarray. HMP Whitemoor, a sophisticated maximum security institution, was recently described by the Chief Inspector as one of the filthiest he had seen, despite being well-staffed and not overcrowded.

Children fare no better. Youth offender institutions, often modern and well-funded, have appalling records. Feltham, the most notorious, has been called the most violent prison in England and Wales. The children’s commissioner for England, Rachel de Souza, has urged that all such institutions be closed—rightly so. They are monuments to moral and managerial failure.

Lammy admits he has inherited a mess—one bequeathed by Shabana Mahmood and a carousel of Tory predecessors who departed before grasping the scale of the problem. The Ministry of Justice is a political graveyard.

Lammy now holds the poisoned chalice. He may yearn for the world stage, but he faces a domestic test: whether justice matters enough for him to stay and fix it. If he commits to remaining long enough to make a difference, he will deserve support—including mine. If not, he will soon join his predecessors.