For years, supporters of international aid have failed to convince the British public that it is worth their hard-earned money. It is therefore hardly surprising that governments find it uniquely easy to make significant cuts to the international development budget without fear of a popular backlash. If we want to build public consent for aid, it is time to go back to first principles and prove that it is worth the money.

Climate finance would be a good place to start. There remains widespread support for tackling climate change, including amongst Conservatives. Many of those who set themselves against net zero do so by arguing that the UK’s contribution to global climate change is too small to make a difference. Climate finance is the tool for making a real difference to rising temperatures beyond the scope of reducing our own emissions.

We need to be realistic: the scale of the finance required to meet global climate goals is enormous, and will not be met with public spending alone. Calling for more and more taxpayers’ money to fill the gap is doomed to fail. We will only be able to justify public spending when we have built public consent. There is no quick fix for this—it will require a fundamental change in mindset and approach, guided by core principles.

Chief amongst these is effectiveness. We cannot hope to convince the public of the benefits of climate finance without a relentless focus on making sure every bit of it is making a real and tangible difference. The UK’s current five year commitment to international climate finance of £11.6bn has achieved some worthwhile outcomes, but have they really delivered the best possible return on our investment?

More money is not the only answer. At a time when budgets are hugely stretched, we have to look beyond expensive programmes. Instead, we should make better use of the UK’s considerable expertise to help climate-vulnerable countries access other investment pots and our technical support in order to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

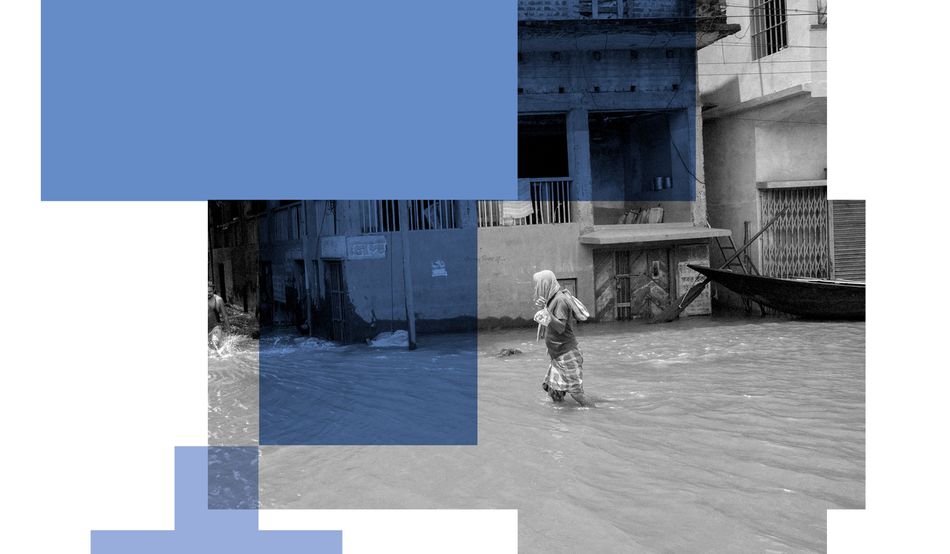

We also need to stop trying to help everybody, everywhere. The UK would make a greater difference by targeting our support at the countries that most need it and where we have the strongest relationships. Prioritising climate finance for Commonwealth nations already facing the consequences of rising temperatures is a step that most people in the UK could get behind.

Another major flaw in our current approach to climate finance is that people in the UK do not see the benefits. While we will clearly gain in the long run from a more stable climate, this will take time to be realised. But in the short term, a more self-interested approach would demonstrate that climate finance spending is worth it now, not just in decades to come.

That means reducing our contributions to organisations like the World Bank and instead putting the vast majority of our aid into bilateral projects in countries where we want, for example, to return foreign criminals, protect key supply chains or counter Chinese influence. That would demonstrate to the public that climate finance can have immediate, tangible benefits for the UK.

The narratives and policies of the past have manifestly failed. Those who believe in the good that UK aid could do have a simple choice—repeat the same failed approach or build a new consensus on climate finance based on targeting our support where it can make the biggest positive difference to the UK’s interests. It’s time for a new approach.