One bright September afternoon in a forest in Switzerland, a 64-year-old woman is about to die. She is standing in a clearing, in front of a purple capsule that’s just large enough to fit a human inside it. “Alright”, she says, as she opens the transparent lid of the pod. She steps in and lies down.

I can hear her breathing.

I am watching a video of the woman in the office of Philip Nitschke in Haarlem, the Netherlands. It’s November and it’s getting dark. He’s trying to show me that the woman died lawfully by euthanasia in the pod, which he invented.

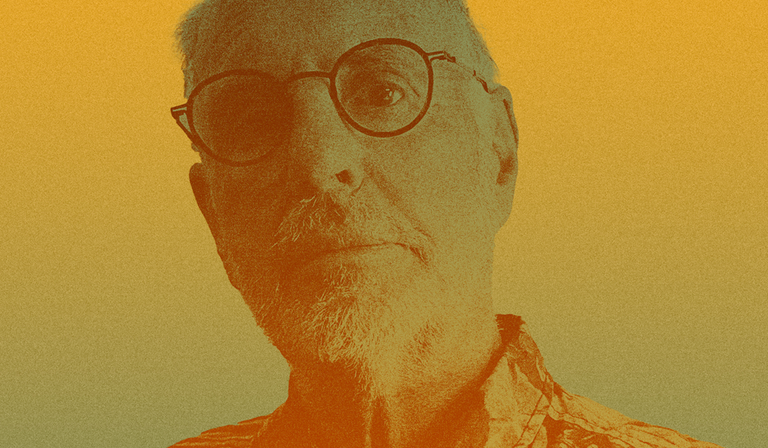

Sometimes called “Dr Death” or the “Elon Musk of assisted suicide”—he’s not particularly keen on either label—Nitschke facilitated the world’s first legal assisted suicides in the 1990s. He’s devoted his life to making death on demand as easy as possible, for anyone who might genuinely want it.

Nitschke designed the Sarco pod I saw in the video, named after Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi, for The Last Resort, a Swiss organisation that provides free assisted suicide. The button inside the pod releases nitrogen, which knocks you out and then starves your brain of oxygen until you die.

He invented the machine to help Tony Nicklinson, the paralysed British right-to-die activist, who wanted to find a way to die of hypoxia—oxygen deprivation—without needing to use his arms (Nicklinson’s pod would have been voice-activated). The pod came far too late for Nicklinson, however, who died in 2012 having refused food after a High Court judge denied his appeal to allow doctors to end his life.

After Nicklinson’s death, Nitschke continued to develop the pod. In 2017, he created it with the help of a Dutch designer, shaping it like a car, as if the dying person was making a journey. He thought that sounded nice. Through the clear lid, they could watch their sky go black.

Florian Willet, president of The Last Resort, remained by the woman’s side in the forest until she died some time between four and five o’clock that day. The police arrived at sunset. They arrested Willet, as well as two of The Last Resort’s lawyers and a photographer who had documented the woman arriving. All have now been released by the Swiss police, who ruled out intentional homicide.

In preparing to help the woman die, The Last Resort had consulted lawyers over how to comply with Swiss law, which prohibits euthanasia for selfish or malicious motives. They had expected the police to be taken aback by the pod, a new and unusual device, and it wasn’t completely surprising, perhaps, that the police wanted to speak to Willet. But the arrests of the photographer and lawyers, who were locked up for two days, baffled Nitschke. “I can’t see that we’ve broken any laws.”

Even worse were the vague allegations of manslaughter and unsupported press suggestions of signs of strangulation on the woman’s body. “It’s really bizarre, because we’ve got this film,” he says. “And the film is pretty clear that she climbed in by herself, unassisted. She pressed the button unassisted. The capsule wasn’t opened until the police arrived.”

The Last Resort was calling for an autopsy to prove there had been no case of foul play. Meanwhile, Willet remained in police custody. On his lawyers’ advice, Nitschke stayed put in the Netherlands.

Dr Death is wiry and tanned, in jeans and a blue-collared shirt, with a houndstooth scarf draped over his shoulders. He has a cloud of white hair and black-rimmed glasses. For a man who has helped a significant number of people end their lives, he is extremely mild-mannered.

Nitschke grew up in South Australia. He studied physics and worked as a park ranger before training to become a doctor. While he was working in a Darwin hospital as a resident medical officer in the 1980s, he heard the chief minister of the Northern Territory of Australia on the radio advocating for euthanasia for the terminally ill. “I thought, yeah, that sounds like a good idea,” he tells me. Most doctors in Australia loudly disagreed, but the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act, which Nitschke campaigned for, passed by five votes and became law in 1996. This was the world’s first assisted dying legislation—a surprise for an area that’s “a bit of a backwater”, Nitschke says. The Northern Territory of Australia is “not known for progressive anything”.

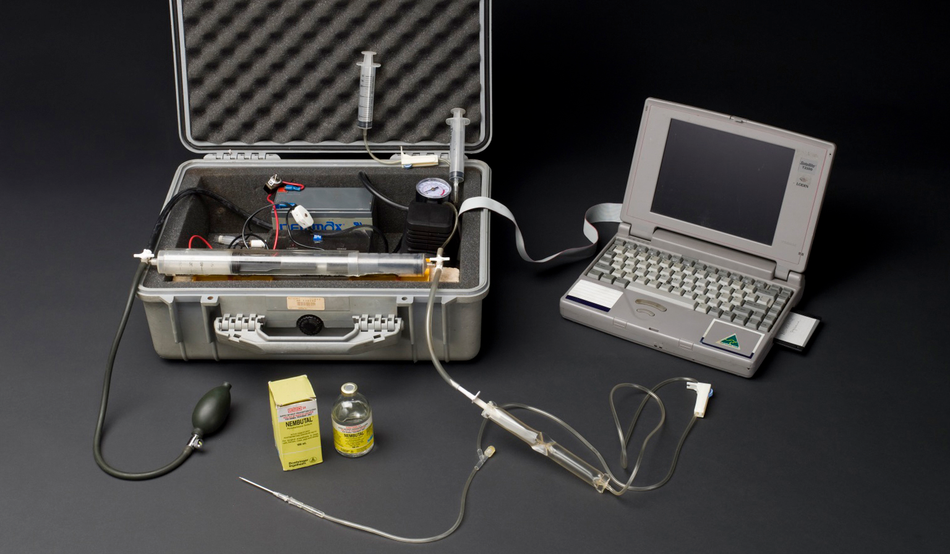

In the next eight months, four Australians in the Northern Territory died legally by lethal injection, and Nitschke assisted each time. “I built a machine, which had a 1996 old laptop running some ancient software,” he says. The machine asked three questions to assess mental competence. Then, a robotic syringe injected the patient with poison. Nitschke preferred the machine to perform the final act. “I didn’t want to be some sort of executioner.”

I ask Nitschke how many deaths he has facilitated in his life. “The only ones I’ve lawfully assisted were the four people in the Northern Territory of Australia,” he says. It’s not quite what I asked.

Nitschke’s first patient was Bob, a man dying of prostate cancer. Bob invited Nitschke over for lunch on a Sunday before his death that afternoon. It was a difficult meal. Nitschke didn’t know what to talk about: obviously, any mention of a future beyond the afternoon was off limits. It wasn’t a particularly hot day, but his shirt was drenched in sweat. Nitschke sat in silence, his mouth too dry to eat his ham sandwich.

Then it was time for Bob to end his life. “The overwhelming feeling I experienced was: thank God the machine’s worked,” Nitschke recalls. “The other thing I did think was: I don’t think life’s ever going to be the same again—and it wasn’t.”

After eight months, and furious campaigning from the medical profession and the church, in 1997 Northern Australia’s assisted dying law was overturned. Nitschke’s euthanasia machine no longer had a legal use.

A Sydney museum asked to put it on display. After a heated debate in the Australian federal parliament about whether it was appropriate to exhibit the machine, the museum told Nitschke that they’d need to keep it hidden in the basement until the fuss died down.

Almost immediately, London’s Science Museum offered to take it. Nitschke flew to England for the handover ceremony. “Occasionally, I’ve had a look at it there in its display in its glass cage. It looks very nice,” he says. “I remember the last time I was there, watching thousands of British schoolchildren filing past, seemingly untraumatised.”

Nitschke was perhaps overestimating British tolerance. A week after our conversation, I went to South Kensington to look for the device in the museum’s death section—but I couldn’t find it. A man at the front desk told me visitors kept complaining, so they moved it to the archives. “It was a bit too morbid.”

In 1997 Nitschke founded Exit International, his organisation devoted to helping people end their lives. He gave out information and organised trips to Mexico, where a potentially fatal barbiturate could be bought legally. He ran to become an independent Australian MP in 2007, in order to push for voluntary euthanasia to be re-legalised, but received only 4 per cent of votes in his electoral division. He announced plans for a “death ship”, registered in the Netherlands where euthanasia had been legalised, that could travel the globe offering assisted dying in international waters—but abandoned it after criticism from the Dutch government.

It was around this time that people started calling him Dr Death. “I found myself suddenly listed in Wikipedia, along with the likes of Joseph Mengele, Harold Shipman and a few other notables. And I thought: my God.”

In 2014, Nigel Brayley, a 45-year-old man suspected of killing his wife, took an overdose after receiving advice on how to end his life from Nitschke. The way Nitschke saw it, Brayley’s suicide was a rational decision: Brayley had committed murder and didn’t want to face a long jail sentence. He saw no problem with advising Brayley to do what he did. The Medical Board of Australia disagreed. It suspended Nitschke’s practitioner’s licence, arguing that he posed “a serious risk to public health and safety”. Nitschke appealed the decision twice, and eventually the Darwin Supreme Court ruled in his favour. He was allowed to practise medicine under 25 conditions, including no longer bringing up the topic of suicide to patients. Nitschke refused. He publicly burned his medical certificate and announced he would leave the profession. He moved to the Netherlands, where euthanasia has been legal since the early 2000s.

Nitschke lives on a houseboat with his wife, Fiona Stewart, a lawyer. His office is all wood and exposed brick, full of books about dog paraphernalia (Stewart has two) and death. On the wall is a poster for Nitschke’s 2015 Edinburgh Fringe show, Dicing with Dr Death. It was a one-man, hour-long performance in which Nitschke advised the audience on how to get around assisted suicide laws. Before each show, the audience were asked to raise their hands to promise they would not use this information to kill themselves (this was not legally binding). “A surreally poor and wrong-headed show, billed (amazingly) as comedy, but emphatically nothing of the kind,” was the Telegraph’s verdict.

Nitschke and Stewart run Exit International together from Haarlem. It now has thousands of members, whose average age is 75. The couple wrote—and regularly update—a guide for members to voluntary euthanasia. The book lists more than a dozen suicide methods, ranking each procedure by how peaceful it is and how likely it is to actually kill you. After it was first published in Australia in 2006 it was swiftly banned, “which is quite an achievement, really”, says Nitschke.

In the pod, there’s a red button. This is what you’d press to die. What a crazy way to go, is all I can think. Nitschke’s face looms outside the plastic windows

In 2017, Nitschke added a chapter on a particular painless poison. The handbook is only published for Exit International members, but the details quickly found their way onto internet forums. The poison was easy to buy, so young people around the world started using it. “That upset a lot of people,” Nitschke tells me. After a young person dies by suicide, bereaved families would be outraged to learn how their relative was able to access the poison that killed them. “You can understand that they were looking for someone to blame.”

In Seattle, Washington, a class action was launched against Amazon for selling the poison without warning of its dangers and Exit International was implicated. Amazon took it off the market. “We survived it,” Nitschke reflects, with a poor choice of words.

In 2023, a Canadian former chef called Kenneth Law was arrested for shipping the poison from Toronto. Next year he will go on trial for the first-degree murder of 14 people. He’s also a suspect in another 120 suicides—including 88 in the UK. Nitschke has been in touch with Law’s lawyers and thinks his charges are unfair, that he’s a suicide assister, not a murderer. “I don’t know how they’re going to try and make that charge of murder stick,” he says.

“I’m upset about the teenagers that have all died thanks to Kenneth Law, but I can give you a list of names of 70-year-olds that are incredibly pleased that Ken Law exists because he sold them this substance, which is getting hard to get, and they’ve got it in the cupboard, and they are feeling happy that it’s there, and they’re living longer because of it.” The way he brushes aside hundreds of perhaps preventable deaths is unnerving.

Still, though Nitschke is a zealot in his belief for the right to die, Exit International has at least tried to tighten restrictions to the support it provides. To obtain a copy of its euthanasia guide, you must provide photographic proof that you are over a certain age, Nitschke tells me. But he is fully aware that each new update takes about 24 hours to hit a suicide chatroom. I ask Nitschke if he regrets that teenagers have died because of information they got from his book. “I often get asked about that,” he says. “But what about these thousands of 80-year-olds who want to have this information, and if they get it, will live longer?” Nitschke believes that for those people, knowing they have a safe way to die will make them feel calmer about death, and therefore choose to live longer. “I’ve got a whole mass of 80-year-olds who are getting upset, worried, anxious and doing precipitous and dangerous things the first time they get a bit of bad news. So it’s very hard to try and trade off those two competing interests.”

It’s a key principle of Exit International that suicide should be free. Here, Nitschke notes pointedly, they differ from other euthanasia clinics, which would set you back at least $10,000. “They always use the same drug,” he says. “It costs about $10, so I’m not sure what happens to the other $9,990.” The Sarco pod—a far cry from the laptop and robotic syringe he used 30 years ago—cost £1m to develop over 10 years.

A week after the woman’s death in the forest last September, Dutch police raided Nitschke’s office and seized some laptops and his Sarco pod, somehow dragging it down the small stairway. “I would like to see [how they took] it,” Nitschke reflects. “It took us a lot of trouble getting it up here.”

In a back room in Nitschke’s office there’s still an older model that the police didn’t seize. It’s white and plastic, bigger and uglier than the sleek car from the woods. It looks a bit like a Portaloo.

Nitschke assures me that it’s not attached to any nitrogen generator, and asks if I’d like to get in. There’s no good reason not to, so I step inside. In the pod, there’s a red button. This is what you’d press to die. What a crazy way to go, is all I can think. Nitschke’s face looms outside the plastic windows.

“I’ve got a bit annoyed that they took my models,” he is saying. “Maybe I should try and make this one into a functioning one.” I get out of the pod.

Nitschke is heartened by the global shift in favour of assisted dying—even in Australia, which legalised it after 20 years of “the dark ages”. He praises Keir Starmer for helping the cause as director of public prosecutions. “I thought then he obviously was very sympathetic… and he understood the issue well.”

He is perhaps not the best advocate for the cause he so believes in. Even pro-voluntary euthanasia campaigners have distanced themselves from his more extreme positions. Your Last Right, an Australian coalition of voluntary assisted dying societies, has specifically opposed Nitschke’s platforms. Rodney Syme, founder of Dying with Dignity Victoria, has called Nitschke’s views “aberrant”.

Nitschke thinks Kim Leadbeater’s assisted dying bill for people with six months to live is “quite a good development”—but it doesn’t go far enough for him. No country does, in his book. Even in Switzerland and the Netherlands, which have more liberal euthanasia laws, psychiatrists are sometimes needed to confirm that those who want to die have mental capacity. “It’s kind of annoying.”

The task of finding a psychiatrist willing to sign off on someone’s death can be extremely tiresome. Nitschke had to search all over Europe to get someone to approve the first Sarco pod death. Now he has a better idea: get AI to screen people instead. “When I get my artificial intelligence process working to check mental capacity—and I’m sure we will, because it’s not just me working on this—we’ll be able to get a person to go, tap, tap, tap, tap, tap, tap… The software will say, ‘Yes, this person has got mental capacity that allows the power to switch on in the Sarco.’” He looks pleased. “That’s the goal in the end.”

A lot of people who get diagnosed with dementia say they’d like to die when they lose control of their cognitive function. The Netherlands is one of only a few countries where you can legally ask your doctor in advance for euthanasia once your condition has deteriorated, even if by that point you no longer know what living or dying mean. But doctors are still squeamish. After all, it’s a lot easier to kill someone who can consent in the moment than someone who may be perfectly happy, with no recollection of why they once wanted to die.

Nitschke thinks he may have found another way to get around doctors in this scenario. He’s working on an implanted “dementia switch” programmed and sewn into your body, probably your leg. If your dementia is so advanced that when the ticking and vibration starts, you ignore it, after a few days the implant would release a millilitre of lethal poison into your body.

It’s macabre—and would be impossible to regulate and safeguard against abuse or pressure, let alone to find doctors willing to insert the implant. Yet Nitschke claims there’s been a lot of interest in the switch. “What you’re doing here is you’re taking responsibility for your own death, rather than hoping that some other person will come along and act on your wish.” Nitschke plans to test the implant soon by sewing it into his own leg. He will use saline solution.

Nitschke has tested other methods of dying, too. He tried hypoxia once, sitting in a chamber as the oxygen level was slowly lowered—similar to the training that pilots undergo in case a plane depressurises. As the level dropped, he had to write a note to test his cognitive functions. It felt quite pleasant while it was happening. But he looked at the note after, and it was complete rubbish. “You’ve sort of lost it, but it wasn’t painful.”

Nitschke is now working on a ‘better, double’ Sarco pod—so two people can die together, holding each other

Nitrogen hypoxia is also used in another kind of legal killing. The first hypoxia execution happened in Alabama, in January last year. Kenneth Eugene Smith had been on death row since he stabbed a woman in 1988, when he was in his 20s. The woman’s husband had offered him $1,000 to kill her.

The state tried to execute Smith by lethal injection in 2022 at the Holman Correctional Facility, which does all of Alabama’s executions, and executed more people than any other US institution last year. Holman staff tried repeatedly to set an IV line in Smith’s veins, repeatedly stabbing his chest and causing him intense pain. After failing to find a vein for nearly four hours, they gave up. This was Alabama’s third consecutive botched lethal injection. The facility decided instead to execute Smith with nitrogen fed through a face mask.

A month before his scheduled death in early 2024, Smith’s lawyer invited Nitschke to Holman, hoping that as an expert in nitrogen hypoxia, he could help make a case against the execution. Nitschke found it dreadful. He tried lying down on the gurney wearing the mask. “It was awful—it was like having an octopus or something on your face.”

Nitschke took a photograph with Smith. He thought he was nice. He wishes he’d given Smith some advice about how to make his death as painless as possible. “I should have said to him, ‘Look, Ken, if you want this process to work, you’ve got to take big, deep breaths. You can’t hold your breath.’”

It seems that Smith, hoping for a last-minute reprieve, held his breath instead. This would’ve made gas leak out of the mask. His death was slow, and his muscles spasmed while he struggled against the restraints. It was described by everyone as “a grim and horrible execution,” Nitschke tells me.

This presented a problem. Campaigners against the death penalty had tried to stop Smith’s execution by arguing that hypoxia is a “cruel and unusual punishment” and contrary to the US constitution. Nitschke, who is strongly against the death penalty, understands why they’d make this case. But unfortunately, it has damaged the reputation of what in his view is a perfectly good way to die.

“They were trying to build up an image of this person being tortured to death.” Suddenly, there were reports about how awful hypoxia is, just as Exit International was planning the world’s first voluntary death by nitrogen hypoxia using the Sarco pod. “We had to try and counter all of the negative press,” he says. “We’ve had to try and explain to our members and all the people that are interested that there’s a world of difference between someone who wants to die, and people who don’t.” Regardless, the death penalty campaigners have not been successful—since Smith’s death, despite appeals, several men in the US have been executed with nitrogen gas.

Nitschke is waiting in Haarlem for prosecutors to decide about the Swiss Sarco case. He’d planned a holiday to the Italian Alps after the first use of the Sarco pod. “And of course, what’s happened now is we’re just totally stuck. The lawyers are saying: ‘Don’t leave the country.’” He sighs. “Trying to find somewhere to walk up and down a hill in the Netherlands is impossible.”

Florian Willet was released after 10 weeks of detention. Allegations of manslaughter by “possible strangulation” of the woman have now been dropped, although a decision has not yet been made about prosecution over an illegal assisted suicide. In Swiss law, this would mean if it was carried out for a “non-altruistic purpose”, that is, for profit or personal gain.

Nitschke is now working on a “better, double” Sarco pod—so two people can die together, holding each other. As for himself, he keeps a bottle of poison in a laboratory near his office. If life gets unbearable, he will drink it. “I suppose I can go in at night and kill myself, and I draw comfort from that.”

A lot of people have died by suicide in Nitschke’s presence. “Almost mid-sentence, they just go off to sleep,” he says. But what happens next? Nitschke doesn’t believe in God. “I have this idea, and it’s quite a comforting idea, that we will decompose into our composing elements and become part of the biosphere and then perhaps be reconstituted into some other form of life,” he says, smiling. “I quite like that idea of the natural process of decay and being broken down into composing elements, that would perhaps lead to the growth of nice trees… ”

The day has ended, and Nitschke needs to go home to the boat. Outside, in the misty black streets of Haarlem, the trees shine with Christmas lights. A cross on a nearby church glows green. The dead—and the dying—could be anywhere.

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this article, you can contact the Samaritans on 116 123