Borrowing from Oscar Wilde, economists are often accused of “knowing the price of everything, and the value of nothing.”

In fact, it turns out that in the 21st century, knowing the price of everything is harder than it seems. At least when it comes to the key things necessary to measure the rate of inflation. We don’t all buy the same things, and with technological change, products improve over time, so a mobile phone today is not the same as a mobile phone 10 years ago. Inflation measures affect vast swathes of our lives; determining pay, pension and benefit rises, school and hospital budget increases, the interest rates set by the Bank of England and the cost of government borrowing. Getting the measure or measures right matters, not least as it has implications for our health and standard of living.

For a dry set of indices, concern over the right measure of inflation has generated a lot of heat in recent years. This debate centres on the continued use of the flawed Retail Price Index (RPI) informing some government policies and the problems caused by having multiple indices. In the summer, the House of Lords Economic Affairs committee recommended the use of a single measure to avoid confusion and reduce government “inflation index shopping”—the practice of choosing the inflation measure that best suits the wider objectives of a particular government. In the chancellor’s Spending Review earlier this month he agreed to phase out RPI but no sooner than 2025.

Inflation shopping is a real issue; the Consumer Price Index (CPI) measure of inflation has tended to be lower than RPI. It’s perhaps no surprise that over recent years the government has switched to CPI where it favours the financial position—benefits uprating and public sector pensions have been switched to CPI. Elsewhere they’ve stuck to RPI—rail fare increases and student loan interest are cases in point. The House of Lords Committee is right: the measure should fit the purpose, not political expediency.

The chancellor is right to phase out RPI—the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reports that there is an error in the way price rises are calculated which means that it’s biased upwards. But any single measure oversimplifies. The business of government is complex and people are not homogeneous. From a health perspective, there are two key issues where measuring inflation appropriately really matters.

The first relates to how the conditions we live in determine so much of our health. Research shows that poverty and financial strain are bad for your health—they act as sources of stress that, over time, wear down the body and its defences. This may help explain why inequalities in health in the UK are wide and widening. If we want to improve health, we must get serious about poverty.

The choice of inflation measure is very important for low income families. Most working age benefits (when not frozen) are now pegged to the historically lower CPI rather than RPI. But the standard CPI measure doesn’t reflect changes in housing costs. The ONS’s Household Cost Indices, currently in development, aim to reflect changes in prices experienced by different household types.

Since 2005 low-income households have seen their cost of living rise almost a fifth faster than high-income households, partly due to housing costs. The poorest 20 per cent of families spend on average a fifth of their income on housing costs, twice the share spent by the richest fifth. They are more likely to rent. An average measure and a measure that doesn’t incorporate this will not reflect the change in prices faced by different groups.

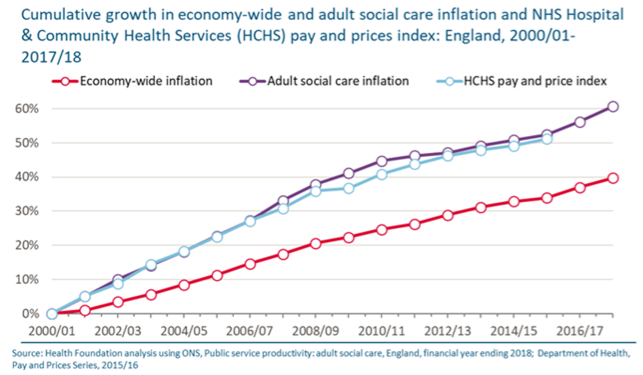

Health is of course also influenced by the quality of the NHS and social care services. As the chart shows, the rate of increase in adult social care and NHS pay and priceshas been around a third greater than economy-wide growth in inflation.

The government measures how much extra it is giving the NHS and social care by comparing it to inflation across the economy. But to assess what quality and range of care can be delivered to patients and service users we also need to understand the specific cost pressures facing these services. Astonishingly, considering the political priority given to the NHS, the Department of Health and Social Care announced last year that “there is insufficient resource to maintain the health sector cost index” which provided more appropriate figures.

There is an appeal in the simplicity of one general measure of inflation. However, it is important to recognise how costs for different groups or services diverge from the average and acknowledge this in the policymaking process. If governments choose not to protect low-income families from their rising cost of living, or allow adult social care funding to fall behind rising pay and price pressures so less people can access care, this should be explicit, not hidden via an unsuitable measure of the financial pressures on those families and services.

It is clearly right that RPI is discontinued. But for the longer term, alongside a new, better general measure of inflation, we also need comprehensive, independent and accurate indices of price changes for different groups in society and different services. Without those, it will be ever harder to ensure that policy is fair and hold governments to account for the consequences of their decisions.

Anita Charlesworth is Director of Research and Economics at the Health Foundation

Adam Tinson is a Senior Analyst (Healthy Lives) at the Health Foundation